I have given lots of talks on climate change over the last few years. In these presentations, I typically focus on explaining the basis of the anthropogenic climate change problem, how it sits in the context of other human and natural changes, and then, how greenhouse gas emissions could be mitigated with the elimination of fossil fuels and substitution with low-carbon replacement technologies such as nuclear fission, renewables of various flavours, energy efficiency, and so on. When question time follows, I regularly get people standing up and saying something along the following lines:

It is all very well to focus on energy technology, and even to mention behavioural changes, but the real problem — the elephant in the room that you’ve ignored — is the size of the human population. No one seems to want to talk about that! About population policy. If we concentrated seriously on ways to reduce population pressure, many other issues would be far easier to solve.

On the face of it, it is hard to disagree with such statements. The human population has growth exponentially from ~650 million in the year 1700 AD to almost 7 billion today. When coupled to our increasing economic expansion and concomitant rising demand for natural resources, this rapid expansion of the human enterprise has put a huge burden on the environment and demands an accelerating depletion of fossil fuels and various high-grade ores, etc. (the Anthropocence Epoch). Obviously, to avoid exhaustion of accessible natural resources, degradation of ecosystems and to counter the need to seek increasingly low-grade mineral resources, large-scale recycling and sustainable use of biotic systems will need to be widely adopted. Of this there is little room for doubt.

So, the huge size of the present-day human population is clearly a major reason why we face so many mounting environmental problems. But does it also follow that population control via various policies is the answer — the best solution — to solving these global problems? It might surprise you to learn that I say NO (at least over meaningful time scales). But, it will take some time to explain why — to work through the nuances, assumptions, sensitivities and global versus region story. So, I’ll explain why I’ve reached this conclusion, and, as always, invite feedback!

So, the huge size of the present-day human population is clearly a major reason why we face so many mounting environmental problems. But does it also follow that population control via various policies is the answer — the best solution — to solving these global problems? It might surprise you to learn that I say NO (at least over meaningful time scales). But, it will take some time to explain why — to work through the nuances, assumptions, sensitivities and global versus region story. So, I’ll explain why I’ve reached this conclusion, and, as always, invite feedback!

Below, I outline some of the basic tools required to come up with some reasonable answers. A huge amount of relevant data on this topic (human demography) is available from the United Nations Population Division, the Human Life-Table Database, the Human Mortality Database, and the U.S. Census Bureau. That data and statistics I cite in these posts come from these sources.

First, let’s look at the global situation. As of 1 July 2011, the human population numbered approximately 6.96 billion people (that’s 6,960 million, give or take a few tens of millions), and is expected to cross 7 billion in March 2012. For historical context, in 1900 it was 1.6 billion, in 1954 it was 3 billion, in 1980 it was 4.5 billion and in 1999 it was 6 billion.

The mid-range forecast is 7.65 billion by 2020, 8.61 billion by 2035, 9.31 billion by 2050 and 10.12 billion by 2100. So, population globally is projected to continue to rise throughout the 21st century, but at a decelerating rate. A summary of a range of scenarios is given in the following table:

The annual growth rate can be calculated as the ratio of one 5-year time period over the previous one, e.g., medium variant 2015 = (7,284,296/6,895,889)^0.2 = 1.1 % per annum. This compares to the peak growth rate of 2.2% in the early 1960s — so it’s clear that population growth is already slowing, but only gradually.

The medium and high variants in the table above indicate no stabilisation of population size until after 2100, while the low variant hits a peak in 2045 with a gradual decline thereafter, reaching the 2001 level once again by the year 2100. The low variant involves assumptions about declining birth rates that are beyond the expectations of most demographers.

In this first post, I want to go beyond the standard UN assumptions to look, in brief, at some more extreme scenarios. I should note here that the model behind these projections is reasonably complex, being based on age-specific mortality and fertility schedules, current cohort-by-cohort inventories (in 5-year-class stages), and the forecast trends in these vital rates over time. In the second post, I’ll explain some of the detail behind this demographic projection model, and explore its sensitivity to various assumptions and parameter estimates. In the third post, I’ll look at the country specific forecasts, from both the developed and developing world. But first, here are some alternative global scenarios, which are not meant to be realistic… merely illustrative.

In this Scenario 1, birth and death rates are locked at those observed during the last 5 years. The 2100 population size is slightly larger than the medium variant from the UN, at 9.4 billion in 2050 and 11.3 billion in 2100. The intrinsic population growth rate (GR) in this model is 0.36% per annum, but due to an unstable initial age structure, the lower equilibrium rate is not reached until 2070. Projecting forward many centuries, to the year 2500, the population size is 47 billion. This is obviously ridiculous — such projections with unchanging vital rates obviously cannot hold over the long term.

Scenario 2 is the UN medium variant, listed in the table above. This assumes that total fertility (TF: number of children a woman would produce over her lifetime if she survived through to menopause) declines from today’s level of 2.5 to 2.03 by the year 2100. There is also a slight decrease in death rates (DR), which I will explain more in the next post.

Scenario 3, illustrated below, is the same as Scenario 2, except total fertility is assumed to decline (linearly) to 1.0 by 2100, rather than to 2.03.

In this case, the 2050 population size is 9.03 billion and 2100 is 7.96 billion. This is still higher than the UN low variant, showing that the low variant requires some fairly heroic fertility assumptions. Looking further into the future, if we assume that TF thereafter stabilises at 1, the global population would eventually decline to less than 1 billion by the year 2210, below 100 million in 2300, and below 1 million in 2460! The underlying GR in this forecast, after 2100, is a decline of 2.73% per annum. So, for effective extinction of the human population to be avoided, either birth rates would once again have to rise at some point after 2100, or else (more likely) death rates would decline substantially to to medical improvements. More on this in the second post on this topic.

Right, let’s go even more extreme, Scenario 4. What if a global TF declines to 1 by the year 2030 — within the next 20 years — which could only be achieved by implementation of a global 1-child per couple policy within a decade or two (I’ll led you judge the likelihood of this…). Here are the results:

In this case, the 2050 population size is 7.03 billion, and 3.79 billion by 2100. The 1 billion mark is passed in 2160, and 100 million in 2245.

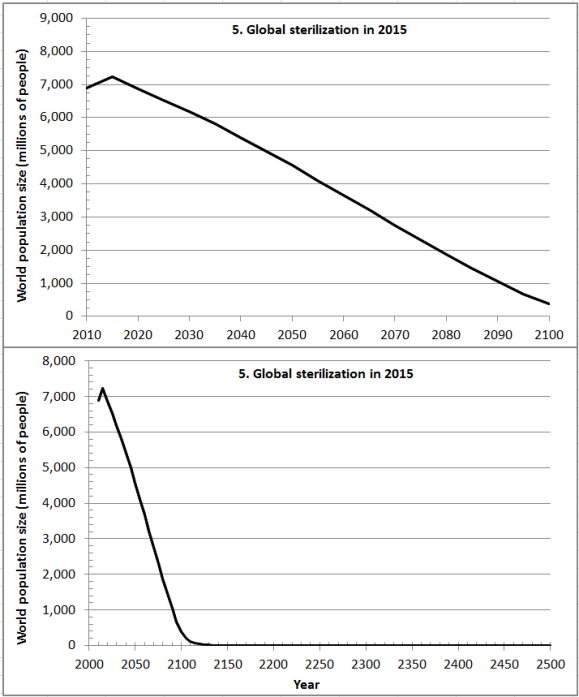

For Scenario 5, let’s assume that some virus or hazardous chemical causes global sterilization by 2015. Here’s what the trajectory looks like.

Population is 4.90 billion in 2050 and crosses 1 billion in about 2090. Virtually everyone is dead by 2120, as you might expect. Now to be fair, the reality of a scenario like this would almost certainly be much worse, because as the population aged with no children, society would quickly fall apart. Most people would probably be dead due to societal collapse by mid-century.

Finally, let’s wind back the TF assumption a bit, but ramp up the death rates. Assume for instance that climate change has caused more famines, disease etc. such that death rates double over the course of the 21st century, rather than decline (as expected) due to improved medical treatments, and TF declines to 1 by 2100.

In this case, Scenario 6, the 2050 global population is 6.89 billion, and it has declined to 2.26 billion by 2100. The 1 billion mark is crossed in 2120, and 100 million in 2160. This seems to be the most plausible of the extremely low variant scenarios that I can possibly justify (I don’t say this is probable). But even in this grim outlook, global population is, in 2050, about the same as today!

The TF = 1 by 2030 (Scenario 4) just does not seem in any way achievable or desirable, and anyway, the total population size in 2050 is still larger than today’s. The conclusion is clear — even if the human collective were to pull as hard as possible on the ‘total fertility’ policy lever, the result would NOT constitute an effective policy for addressing climate change, for which we need to have major solutions well under way by 2050 and essentially wrapped up by 2100.

In summary, I support policies to encourage global society to achieve the low growth variant UN scenario. (More on that in the next post). But I must underscore the point that population control policy is patently not the ‘elephant in the room’ that many claim — it’s more like a herd of goats that’s eaten down your garden, and is still there, munching away…

64 replies on “Why population policy will not solve climate change”

Following. Quite illuminating.

LikeLike

Your post makes quite clear that it takes several decades at least for population numbers to react to any changes in the scenario input.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that population control is not the answer.

Global warming will be a problem fifty years from now as well, and very likely very much more so than today. So the slow reaction time of the system does not mean “let’s wait and do nothing to address population”. Quite on the contrary, it means that these measures need to start as soon as possible.

LikeLike

Surely the best way to implement effecive population control is to let demographics take its natural course in an affluent society. The primary thing therefore is to assure affluence as far as possible on a firm base of nuclear power generation.

LikeLike

“The human population has growth exponentially from ~650 million in the year 1700 AD to almost 7 billion today. ”

Barry, this is emphatically not true. Population growth has been a tad less than linear since the 1970’s.

MODERATOR

References please.

LikeLike

Karl-Friedrich Lenz, on 19 September 2011 at 11:07 PM said:

So the slow reaction time of the system does not mean “let’s wait and do nothing to address population”

I don’t think we can say ‘nothing’ is being done to address population.

Global Fertility rates have been dropping by 1/2 a child per female every 10 years since 1960. Globally we are still 1/2 a child per female above replacement.

http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&met_y=sp_dyn_tfrt_in&tdim=true&dl=en&hl=en&q=world+total+fertility+rate#ctype=l&strail=false&nselm=h&met_y=sp_dyn_tfrt_in&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=country&ifdim=country&tdim=true&hl=en&dl=en

LikeLike

Nest time one of these (pejorative deleted) (people) asks that question, instead of answering directly, ask this question in return: “If you really believe the best answer is to reduce humanity’s numbers by X%, if you’re not a hypocrite, why haven’t you already killed yourself?”

When most people think of the Middle Ages, they imagine themselves as noble lords/ladies, not as peasants. Thus, many actually do approve slavery, since they expect to be the master. Only when they get slapped in the face by the reality that modern equality is just that–modern–that they begin to understand that life, liberty, et cetera were scarce to rare (when they existed at all) in the historical past. Those looking to reduce the population fall into the same category of self-decievers for the same reason.

Ron Pittenger, Heretic

LikeLike

I’m not sure what is meant by “population control measures”, but it sounds both draconian and ineffective.

Education, women’s equality, democracy, and economic development are the path to population stabilization. Look at population curves in the developed world and this is patently obvious. Do the right things, and population takes care of itself.

We’re still going to need cheap, abundant energy to fuel human society and make it sustainable.

LikeLike

Population is a root cause of many problems including climate change, as you admit. Another way to chart it is to expand the timescale out a few tens of thousands of years. You’ll see a flat line, a relatively low and relatively stable global population going on for thousands of years, then the line goes straight up doubling and redoubling, relatively instantly. That line has to stop going up at that rate at some point or no problem is going to be solved.

I’m not sure what you mean by “elephant in the room”. Your point appears to be that there isn’t anything ethical civilization might be able to do about population that by itself would solve the climate problem by 2050 or 2100. Are you saying the people who as you say “regularly” stand up after your talks to bring population up disagree? You characterize them as saying “other issues would be easier to solve” if population pressure could be reduced. I don’t see what’s wrong with that. I don’t see the contradiction between what you say they say, i.e. in the highlighted box, and what you appear to believe.

It can’t be that people are “regularly” standing up after your talks to say don’t bother to limit emissions, just take an axe to the global population, that’s the solution.

Population was more central to the nascent climate debate, and to the broader environmental debate back in the late 1980s. The UN set up the Brundtland Commission which toured the five continents for years in the middle of that decade seeking input from anyone in the world who had thought about the “environmental” problems civilization faced. They then published “Our Common Future“, which became known as The Brundtland Report, which they described as an “emergency call” from the UN. This was the publication that coined the term “Sustainable Development”. The report was an excellent survey of global environment problems.

The basis of the action plan in it was to put a cap on global population.

It had been observed that population was increasing most rapidly where people were poor, while in some parts of the developed world actually faced the prospect of population decline. “Sustainable Development” was a plan to increase living standards in the poor areas of the world where most population growth was occuring so that birth rates would decline. Economists weighed in with estimates of how quickly economic growth could occur and demographers had their say.

It was held to be realistic to expect that global population stability could be achieved at about 10 billion people by 2050, all living at something like the living standard then prevailing in the developed world.

About one billion people with a relatively stable population were living the developed world lifestyle in the late 1980s, while the four billion poor people who were rapidly expanding their population.

You didn’t have to be a rocket scientist to understand that “Sustainable Develpment” meant an expansion of the developed world civilization by an order of magnitude. The 1 billion who lived then mostly in North America, Europe and Japan, said by Brundtland to be using 80% of Earth’s resources, were to become 10 billion living the same way worldwide, before human population could stabilize. Obviously, 800% of the Earth’s resources were not going to be found.

Throw in all the technology you want to imagine, keep in mind the documented problems that minuscule 1 billion people were already causing to the planetary system, and the prospects then looked daunting.

And Brundtland published prior to the confirmation that the ozone hole was indeed the first confirmed damage to a global system essential for this age of life caused by the wastes of civilization. What was then more often called “global warming”, or “the enhanced greenhouse effect” had yet to hit the front page.

Because “Sustainable Development” spelled this all out so clearly, i.e. that many of the then best thinkers in the world about these issues had decided that the problems caused by the dramatic expansion of civilization could only be “solved” by further massive expansion of that same civilizationm by an order of magnitude, the plan became controversial. Many critics called the plan an “oxymoron”.

I called it a delusion. I found out where Prime Minister Brundtland and Maurice Strong (Chairman of the Rio Earth Summit) were having dinner together one night at a hotel, and, posing as a waiter, I arrived at their table with a bottle of my “Dr Brundtland’s Sustainable Development Delusion”, which I managed to present to them as if they had just ordered it, before security arrived to ask me to leave. I digress.

Hence the word “sustainability” entered the debate. “Sustainability” had no actual global plan attached to it. Everyone could be for “sustainability” as something a bit better than would otherwise have happened had they not been for it, and the “elephant in the room” remained.

It isn’t so much that “population” is the elephant in the room, or that capping its expansion is the solution to all or any problems. What solution will be found if population never stops growing? Brundtland at least was clear that what mattered was what that population does.

We might think population is “only” doubling from the 5 billion that there were in the late 1980s to the projected 10 billion or so by 2050, but as I’ve pointed out, the potential impact the the biosphere faces is that of a developed world civilization expanding by a factor of 10.

I don’t think we have anything like a shared vision of how 10 billion people might live on this planet even if that population was stable over some long term.

On just one issue, we don’t know what the present level of GHG has already committed the planet to experience. Hansen is saying the Milankovich forcing that drove changes as large as moving from an interglacial to an ice age is far smaller than the anthropogenic forcings that have already been added by us to the system. He and many others warn about the non-linear climate changes no model can predict that paleoclimate studies indicate must be in store.

Now as we see, it wasn’t necessary for the UN or any organized group of countries to implement policy aimed at expanding economic growth in the developing world so that global population might stop rising. China and India are growing faster economically than was thought possible decades ago. It remains to be seen if India’s population will stabilize as a result. We are experiencing something that looks very much like the dramatic expansion of the developed world the “Sustainable Development” vision said we should aim for. It doesn’t look that sustainable,

Back in the 1980s the only way I could see civilization surviving, in the terms Brundtland was using, was instead of assuming the developed world would not and could not live on less and defining as “sustainable” a future where all 10 billion by 2050 lived at the developed world standard, was to call for civilization to change what it values and for people to change what they expect to do. My critique of “Sustainable Development” was fairly simple and not fleshed out much: this isn’t going to work, so we’ll need our best people to step forward and work together to find another way.

LikeLike

Robert Hargraves has put forward the most practical and least painful solution.

1. Access to large amounts of reliable and affordable energy (actually useful work – efficiency counts) greatly increases society’s affluence.

2. Affluence decreases fertility to very stable replacement rates.

3. Ergo increasing the reliable affordable useful work available to societies around the world stabilizes world population.

LikeLike

The Chinese have already given us an example of population growth control, and we can see from their GHG emissions that this is pretty irrelevant.

LikeLike

As the graph referenced by harrywr2 shows the fertility rates have dropping steadily for decades. North America, Europe, China and Japan are already below ZPG and worldwide we should be below 2.2 children per women in a couple of decades. Instead of overwhelming population growth, many countries are concerned with becoming nations of Struldbrugs without enough young people to support their population of elderly people.

There is little or support for a rebound in the fertility rate. We will probably max out at 9 or 10 billion and see a decline from there.

The advocate of decreasing fertility rates further apparently have not looked at current fertility rates or seem to be advocating a policy of genocide.

LikeLike

Fertility rates are highest where poverty is the greatest and lowest where affluence is the greatest. Poor people need more children to help keep the family alive (see for example, Mahmood Mamdani’s book The Myth of Population Control).

Therefore the only way, it seems to me, to address population issues is to create a world in which poverty is eliminated, and that requires an end to the profit system that thrives on impoverishment of the many and necessarily applies a short term outlook to every problem.

LikeLike

Given enough global warming the world population will be reduced by famine disease and war. Political intervention will be unecessary in this situation.

LikeLike

I think we’re heading for severe resource constraints well before 2050 and even 7 bn is far too many. Ignoring CO2 abatement the constraints include supply of liquid fuel, concentrated phosphate, water reliability and finding enough capital for cleantech. The evidence is already there with people jumping on leaky boats to relocate or Chindia with 2.5 bn people buying coal mines in Australia and tar sand operations in Canada.

Thus the article’s basic premise may be correct in that we will have burned up all fossils fuels (down to low net energy) whether there are few of us or many. A sobering thought is that if we currently need 15 TW for 7 bn people we’ll need more in future, but maybe 12 TW of that is the fossil one-off. That is future people will need 20 TW of non-fossil. If we still have 7 bn by 2050 times will be tough, the fossil fuel party having died down leaving a climate mess to clean up.

LikeLike

(Warning, satire alert): But Barry, you’ve used modeling. Everybody knows how unreliable modeling is. We can’t base policy on modeling, much better to base it on hunches and what our financial backers can

make money out of.

LikeLike

Reminds me of a saying—“all models are wrong. Some models are useful”

LikeLike

A chart in a link given in the open thread by Mark Duffett suggests world energy supplies are currently 76% met by fossil fuels.

Given crude oil peaked in 2006, all-liquid fuels are set to peak within 5 years, coal should peak by 2030 and gas by 2040 I’d say we’ll be in some strife by 2050. Great, simultaneous world energy poverty and a buggered climate.

LikeLike

A population range of 4.9-9.4 billion in 2050, with the low end scenario basically being the apocalyptic plot line of “Children of Men”. Nice one Barry. Way to put some incredibly obvious numbers (not meant to belittle your efforts, more to point out that the issue is not as complex as all that) behind the answer we need when that question is asked. And it is asked, all the time, and yes some people do seem to want to use it as a crutch to avoid lending support to action that might lead to intellectual discomfort, like thinking in a clear-headed way about nuclear power, or suggesting that we might need stricter regulation to ramp up our efforts in energy efficiency, or eating less meat.

Someone I know (runs a blog with 3 million hits) once quipped “We can address population, but slowly. I can have ten children but I can only die once”.

LikeLike

For online dynamic historical data don’t forget to have a play with Gapminder:-

http://www.gapminder.org

LikeLike

Barry – “the elephant in the room that you’ve ignored — is the size of the human population”

While it is good that you are looking at this population, SIZE is not the only problem. It is a combination of size and the amount that the population consumes/pollutes that is the problem.

At the start of Chapter 7 of “Limits to Growth – the Thirty Year Update” is this:

“The structural causes of overshoot over which people have the most power are the ones that we did not change in Chapter 6, namely those that drive the positive feedback loops causing exponential growth in human population and physical capital. They are the norms, goals , expectations, pressures, incentives and costs that cause people to bear more than a replacement number of children ……….. that make people see themselves as primarily as consumers and producers, that associate social status with material or financial accumulation, and that define goals as getting more rather than giving more or having enough.”

Basically what this is saying that limiting the Earth’s population will not help climate change as you state but not because of the reasons you give. Even a reduced human population that all aspired to have a Western standard of living would still cause overshoot and collapse. In the scenerio described in Chapter 7 some of these constraints were changed. The economy was assumed not to grow and people were assumed to be able to live with the concept of suffiency rather than consuming. The population did actually stabilise at a reasonable amount.

The point is that population alone is not the elephant in the room. Consumption and pollution plus the ever increasing use of the Earths sinks coupled with ever decreasing natural resources are the problems. Which is exactly why just increasing the energy supply is not the whole answer. Additionally if unlimited energy was the answer why has it not solved the Earth’s problems in the last century of unlimited and cheap fossil fuelled energy?

LikeLike

For a start, fossil fuels are not unlimited, they’ve been much more favourable to those nations with domestic supplies, and wars have been fought over them. Secondly, no one has claimed it is the answer to all of the world’s problems (again with this straw man argument?).

LikeLike

The graphs could be made to show modelling for uncertainty divergence. If a purely random variation of quite small amplitude were added on a period of perhaps 30 years or so, I think you would find that an ensemble of modelling runs would diverge away from each other on the scale of centuries. Then, if regions where allowed to vary independently, perhaps on sub-populations of 100 million or so, it would be the regions that diverge from each other.

However, unforeseen variations are not random. They are history, history that we’re going to learn about once it has happened to us.

LikeLike

It’s surprising to find that some people actually advocate for a prolonged global depression.

LikeLike

Tom Keen – “For a start, fossil fuels are not unlimited, they’ve been much more favourable to those nations with domestic supplies,”

Which is true for all forms of energy not just fossil fuels. However up until about 20 years ago when we really became aware of climate change the energy was unlimited. For thirty of those years there was nuclear power as well. The take home point is that increased material wealth means more exploitation of resources. The energy supply simple facilitates this exploitation.

“Secondly, no one has claimed it is the answer to all of the world’s problems (again with this straw man argument?).”

You have read Prescription for the Planet haven’t you??

LikeLike

TerjeP – “It’s surprising to find that some people actually advocate for a prolonged global depression.”

Almost as surprising as people who think endless exponential growth is possible in a world with finite resources.

No growth does not mean depression. There are many systems of economics that have been modelled that do not depend on growth and are still vibrant and changing. In exactly the same way Nature stays mostly in balance over very large time periods.

http://steadystate.org/

http://www.energybulletin.net/node/52757

LikeLike

The Three Ways Out

By George Taylor

Posted on Jan. 15, 2007

Any prudent observer would consider the possibility that fossil fuels might run short within years and very short within decades. Given that we depend on oil, natural gas, and coal for 90 percent of our energy, we could be facing the most catastrophic change in modern history. Equally scary, even should more fossil fuels be discovered, burning them without storing away the carbon dioxide they produce could cause global warming.

The False Ways Out

Many purported ways out are false hopes, either because they are too small to matter or because they have a fatal flaw.

– Hydroelectric power is low-cost, but cannot be expanded.

– Geothermal is available in only a few locations, and likewise cannot be expanded.

– Wind has huge potential capacity, but even in the best locations only blows fast enough to turn the windmills one-third of the time. Its fatal flaw is that we have no storage mechanism for electricity today, and none of the proposed ones would return more than 25 percent of the energy that goes in. The electricity produced by windmills could be used to make liquid fuels, but such transformations are very wasteful. If battery technology improves enough, hybrid-electric or pure electric vehicles may be the wave of the future, and full-time electric power plants (such as coal or nuclear) would avoid the conversions required by intermittent ones, such as wind or solar.

– Photovoltaic solar is many times more expensive than competing technologies, and will remain so indefinitely because sunlight is weak, the physical infrastructure costs are huge, and the sun delivers only about two thousand effective hours per year (25 percent), even in the desert. Plus, solar has the same flaw as wind: we can’t store it. Thus, while it may address peak electricity demand on a summer afternoon, it would not be reliable enough to power the world.

– Biomass as currently practiced – corn ethanol or soybean diesel – produces such small net gains in energy that no amount of farmland could ever replace a meaningful portion of our fossil fuel consumption. Corn ethanol is just a way to convert natural gas (through fertilizer and steam) into a liquid fuel. It has only gained traction because of the temporary availability of natural gas at prices lower than oil, state-level mandates, and federal-level subsidies (of 75 cents per gasoline-equivalent gallon). Soy diesel, in contrast, can be produced at a small profit, but only because we need the soy protein first. Even so, net production of 35 gallons per acre would yield less than 1 percent of U.S. petroleum consumption (2.5 billion gallons) even if all 75 million acres of soybeans were utilized. The only biomass that hasn’t been discredited as a serious energy source is cellulosic alcohol – because the proposals for it are so poorly defined no one can say what they mean. We should be skeptical because cellulose is far more difficult to break down than corn or soybeans, and the lignin that cellulose advocates propose to use for process heat is as little as 20 percent of fast-growing plants.

– Finally, while both the world and the U.S. have a lot of coal, we have yet to demonstrate even one case of large-scale long-term storage of CO2.

The Real Ways Out

Fortunately, we won’t have to live in the dark or melt all the glaciers. Conservation, efficiency, and nuclear power are real ways out.

Cutting demand (conservation) won’t be popular, but we could take at least one significant step – by curbing population growth. By 2050, the path we’re on will add 150 million people to the 300 million we reached in the U.S. this year. But the growth is driven almost entirely by immigration levels set by Congress, which Congress has the power to reduce. They just haven’t made the connection between population and energy.

Increased efficiency, particularly in transportation, space heating, and electric appliances, could generate huge savings, and many observers claim the first 50 percent reduction could be achieved with little impact on quality of life. Higher-mileage cars, better insulation, and more efficient lighting could go a long way.

But after all that, we will still need a massive source of reliable, long-lasting, low-pollution energy. And, except for a huge piece of luck, there might have been none. But we’re lucky, and one exists – nuclear fission. If, over the next 50 years, we built a thousand one-gigawatt nuclear power plants in the best known way, we could simultaneously: 1) meet all of our energy needs at reasonable cost, 2) operate them more safely than any other large-scale technology ever deployed, 3) reduce greenhouse gas emissions to a fraction of their current rate, 4) solve the waste disposal problem, 5) have a fuel supply that would last forever, and 6) add nothing to the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation.

The fundamental reason is that nuclear forces are vastly stronger than chemical bonds – about 3 million times stronger, if you compare the weight of uranium to the energy-equivalent weight of coal.

The way to unlock uranium’s full potential while minimizing its harmful by-products is to change from today’s open fuel cycle to a closed one, and from today’s fleet of light-water reactors to one containing at least some so-called fast reactors. A closed fuel cycle means reprocessing the spent fuel, in order to send the unused uranium and the created undesirable trans-uranium elements back into the reactor to be split apart, thereby releasing more energy. Only the fission products – the smaller atoms created when large ones break – would be sent to a repository. Fast reactors, which are named after the higher-energy neutrons they utilize, would serve two purposes – to burn up the trans-uranium elements and to breed new fuel (hence, the name breeder reactors) by converting the 99 percent of uranium which will not normally split into plutonium atoms which will. Light-water reactors do this, too, but on too small a scale to keep the process going. Thus they require far higher quantities of fresh uranium.

The differences would be dramatic – over 100 times more energy per ton of uranium in, and 20 times less waste per gigawatt-year of electricity produced. Even more important, the waste stream would contain so little radioactive material that after 500 years it would be no more radioactive than uranium ore in the ground. Repositories such as Yucca Mountain could be simplified or even eliminated.

How could these claims be true, you ask, since we rarely hear anyone talking about them? Because after Three Mile Island, the nuclear industry had to improve its procedures and designs, nuclear power’s opponents stopped all rational discussion, and natural gas was plentiful and cheap for a couple of decades. Nuclear power genuinely had a problem, but that’s changed.

Let’s look at these claims. Nuclear is safe enough, because even an accident which caused a large economic loss, such as Three Mile Island, harmed no one. The defense-in-depth design did what it was supposed to do, and the industry learned and applied many lessons to reduce the chance of a similar accident. We would have greenhouse gas reductions, because nuclear fission emits none. And there would be non-proliferation, because all the proposed fuel cycles mix materials in ways which would make recycled fuel undesirable for weapons design and dangerous to handle.

Nuclear power can be had at reasonable cost because: 1) the 2005 energy bill solved the unpredictable licensing process by mandating a single license for construction and operation, 2) because fast reactors will keep nuclear fuel inexpensive, and 3) because nuclear waste can be reduced to a small problem by reprocessing steps that would cost less, some say far less, than one cent per kilowatt-hour (about 12 percent of today’s average retail price).

Not that all of this will be simple. The development of closed fuel cycles and fast reactors is not yet finished. But what’s left is engineering, not the discovery of new solutions. It will take decades to build a thousand reactors, but that just underlines the task’s urgency. We can’t wait until there’s a crisis to start developing solutions, and we can’t afford to waste time on false hopes.

George Taylor is a writer in Los Altos, California who is researching a book on the feasibility, economics, and environmental impacts of all practical sources of primary energy for the next 50 years.

MODERATOR

George- whilst this is interesting, it is off-topic on this thread and should be re-posted on the current Open Thread or a suitable thread discussing nuclear power. We do not have the facility to move comments and, as per BNC Comments Policy, future off-topic remarks may be deleted.

LikeLike

‘It’s surprising to find that some people actually advocate for a prolonged global depression.’

I’d like a chicken in every pot and a car in every garage. But if that means frying the planet I suppose I could become a vegetarian pedestrian. Don’t have to like it

LikeLike

Barry,

As someone who feels population growth is a problem I see your reasoning on the change in numbers and growth in those numbers.

Thanks as you have eased my mind on population numbers in general terms so then it becomes how the population affects GHG emissions and land use over the course of the 21st century. For example, might an ageing population be beneficial in reducing GHG emissions because overall less people will be scurrying around frantically around doing stuff or will this be masked by populations in developing countries adopting high emissions techniques to improve prosperity.

(I have to confess I don’t follow that particular religious cult present in Australia that worships ever increasing population to appease the god of growth).

LikeLike

For the record, I’m opposed to all you neo-Malthusians out there. I don’t deny the possible upper carrying capability of the planet but deny that technology and technique are static, which is what you doing assuming there are no advances in agriculture, family planning, water management and technology, etc is silly. I’m reacting here to the commentary and not Barry’s entry, specifically as he is giving an overall “What If?” analysis not trying to prescribe solutions.

The idea we can’t support a population of 9 billion is simply unproven. It’s unproven because we don’t know what the application of new methods of technology using high-energy applications for things like…water…probably a bigger and more important resource than oil..will entail. It’s not guaranteed but boy, if I went by you guy’s pessimism, I might as well off myself now and be done with it.

This is because none of you are really demonstrating any belief in the ability of our species to *solve* problems. We have a world that is *mostly* water which we can use as a renewable resource; we have explored less than 1% of the crust of the planet below 500 meters; we have not even applied advanced reactor technology to the worlds political-economy *at all* to see if, using the same models, we can find solutions to the climate as well as general resource hunger.

You guys are such downers.

LikeLike

See: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol16/iss2/art27/

Look at the figures. The prices of fuel and food have begun their takeoff.

Unplan most likely: Famine kills all but about 700,000 some time between 2050 and 2055. Between now and then, the 4 horsemen of the apocalypse ride. Or is it 7 horsemen now? Regional nuclear wars happen: India vs China, for example. Civil wars kill a few billion. We may go extinct, or human evolution may once again be driven by climate change. The genetic change we need is more math and science IQ.

The history of civilization repeats.

Alternative unplan: Pandemic kills all but about 1 Million any old time.

Think up your own unplan.

What should have happened: We should have colonized space while our population was only 3 billion.

LikeLike

Not until we can figure out how to seriously shield the massive amount of radiation cosmic radiation and, the biggest problem, gravity.

LikeLike

See book: “Population politics: the choices that shape our future” by Virginia Abernethy, New York : Insight Books, ©1993. xix, 350 p. : ill. Library of Congress call number: HB883.5 .A23 1993.

LikeLike

David Walters: See http://www.liftport.com/

LikeLike

AM,

No Dilithium crystals means no space travel.

Get it.

We can’t even get Nuclear power plants in.

LikeLike

Interesting discussion, even if some contributions are somewhat circular and/or repetitive, but that is a feature of all blogs.

Thanks for stirring the population pot, Barry. I look forward to the next instalment.

LikeLike

I agree on the circularity JB. The fundamental point, that seems to be regularly skimmed over, is not that we ought to do nothing about population size (increasing affluence/education of women seems to be the most effective measure), and not that this shouldn’t be an important focus today, but that whatever we do, its effects will be irrelevant for things like environmental damage and climate change over the 21st century. It’s just too slow.

LikeLike

‘It’s just too slow.’

I don’t think I would agree with this. The change in fertility rates as affluence/education of women increases, has been amazing over the last 50 years. From the UN – total world fertility rates.

1950-1955 — 4.95

2005-2010 — 2.52

LikeLike

@Steve While the decline in fertility has been rapid, it is slowing, and the next 0.5 children/woman of decline we need to get to a gently falling population is expected to take a century (UN median projection, Scenario 2, above) while the last one took only 16 years (See link in comment #5, by harrywr2). As Barry points out, even if the fertility decline was faster, the population keeps rising for a while, and cannot decline much before 2050 in any circumstance short of global disaster, because ~3 billion people likely to be alive in 2050 have already been born. Half the world’s population is still under 30

http://www.indexmundi.com/world/demographics_profile.html

although that will not be true much longer.

LikeLike

Luke_UK, on 22 September 2011 at 1:48 AM said:

While the decline in fertility has been rapid, it is slowing, and the next 0.5 children/woman of decline we need to get to a gently falling population is expected to take a century

The time lag from the time one actually has successfully implemented universal education for woman and when the effects show up in the fertility rates is on the order of 20-30 years. For a good portion of the world that time lag has already passed.

Unfortunately, we still have some notable pockets in the world where educating woman is not only not a priority but is forbidden.

Opening and keeping open the girls schools in Afghanistan has not been a trivial task.

We also have places in the World where universal education of girls is a policy but the actual attendance rates fall well short of ‘universal’.

LikeLike

re: time lags.

The biggest lag time problem we face is the lag time associated w/ bringing Nuclear power online. My gut feel is that it will take until 2050 or maybe 2100 till the world population figures out that the only hope for surviving the warming trend is to deploy lots of Nuclear.

Will it be too late by then??

Can the world population survive in a +3 deg C warmer planet??

It would be interesting to see an analysis similer to the one done in the last thread on “Switching from Coal to Natural gas” https://bravenewclimate.com/2011/09/11/switching-coal-to-gas-cc/ only we switch from today’s power generation mix to Nuclear at different rates and what the predicted warming trends result.

LikeLike

“Poor people need more children to help keep the family alive”.

I’d like to complete Bill Sacks’ statement:

For the poor to help keep the family alive, one strategy is indeed having more children — yet another one is, having them as early as possible.

I find it amazing that such a lot of learned people on this forum are talking 100% consensually about total fertility (TF), i.e. total birth rate as the basic parameter to derive population growth or decline from.

If I inform you that the next town is 2 hours away, what does it tell you? Nothing worthwile — you have to know whether it’s 2 hours walking or two hours driving and even then you want to know at which speed, e.g. miles per hour.

To extrapolate a given population’s growth or decline rate from the average number of children per woman of that population is impossible unless you also know the mean age of motherhood.

Here’s an example, comparing two populations with the same TF of 2 children per woman:

In the first population the mean age of motherhood is say 20 (e.g. first child at 19, second at 21, on average), whereas in the second population the mean age of motherhood is say 40 (e.g first child at 39, second at 41, on average).

I let you do the maths to figure out at which pace the first population will outnumber the second…

LikeLike

This might be a little off topic, but every time I see phrases like “We’re using eight Earths worth of resources!” I do find myself a little curious what the breakdown of these resources is. Then it might be possible to have a somewhat more coherent discussion of what the exact problem areas are and potential solutions.

What are we talking about here?

Energy? Phosphorus? Arable land? Water? Industrially useful chemical elements? Biodiversity?

I know it’s going to add up to ‘All of the above’ obviously but some of those have relatively easy solutions (nuclear power), some of them will be solved or at lest alleviated when you solve another (nuclear driven desalination), some are legitimate worries I’ve yet to see an answer for and others like having enough aluminum and iron fall into the “That’s the last thing I’d worry about” bin.

LikeLike

Somewhat related to Nick’s questions is the fine reporting by George Musser in

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2011/09/23/how-life-arose-on-earth-and-how-a-singularity-might-bring-it-down/

LikeLike

[…] question For the time being I'm not going to comment on it but I want to at least get Barry's interesting perspective out there. You are also free to offer commentaries on his […]

LikeLike

The low variant would be roughly 8 billion people by 2050. That means 40 years of population growth and if I understand past comments, close to a trillion dollars a year to replace fossil fuel with nuclear power plants.

What I’d like is a full spectrum of experts on energy, climate science, ecology, agronomy, marine experts, environmental economists, population experts, urban planners etc. etc. to give their opinion and if they accept such an approach as both plausible and useful have them provide us with at least a rough scenario of how we take this approach to sustainability.

LikeLike

David M:

You use the word “sustainability”.

This means different things to different folks and to some brings with it considerable emotive baggage. For example, is solar power sustainable, in that our sun must eventually run out of hydrogen to convert to helium. Is geothermal power “sustainable”, given that it draws upon heat generated within the earth by nuclear fission? Is nuclear fission within an engineered environment “sustainable”?

I put to you that no process involving energy, in the extreme analysis, is purely and for ever sustainable. However, you have used this emotive word as a qualifier in your contribution.

Please define this term as it applies to your comment posted 25. September at 25pm.

LikeLike

John, I applied the term sustainability in the most ordinary conversational sense – living with Mother Nature in a manner that sustains our life well into the future. The counterpoint would be say continuing to use fossil fuel, propelling us into a 6th extinction event, hardly a sustainable condition. Add to that overshoot in vital resources and general pollution, all of which seems intimately related to population.

Most of us aren’t engineers and don’t take terminology like this in such a technical way. But if sustainability seems odd try “an environmentally stable future.”

LikeLike

euroflycars, on 25 September 2011 at 6:45 AM said:

I find it amazing that such a lot of learned people on this forum are talking 100% consensually about total fertility (TF), i.e. total birth rate as the basic parameter to derive population growth or decline from.

Total fertility is a leading indicator. I.E. Once total fertility drops to replacement at some point in the future population growth will be zero.

To determine ‘when’ population will stabilize once TF has dropped to replacement one does indeed know the average age of child bearing as well as live expectancy.

I.E. Life expectancy in Afghanistan is 44 years. If the average age of child bearing is 14 years old then if TF dropped to replacement tomorrow morning at 9 AM population will stabilize in about 30 years absent an increase in life expectancy.

.

The UN has a nice 250 page report on population growth until 2300 here –

Click to access WorldPop2300final.pdf

To quote –

Convergence in fertility underlies this convergence

in population growth. Curves representing

total fertility trends (figure 19) in fact resemble

curves for population growth, with the qualification

that the turning points in fertility come about

50 years earlier.

If I look at the nice chart the UN prepared on page 25 of their report fertility rate equaled net replacement rate for North America in 1970, Europe in 1978, Oceania in 2010 and is expected to reach net replacement rate in Latin America and Asia by 2015.

For Oceania the fertility rates in Papa New Guinea are masking Australia’s much earlier drop in fertility rates.

Africa is indeed a problem scenario where fertility isn’t expect to equal net replacement until 2050.

LikeLike

(Deleted pejorative.)

Your article although deep in research is all non-sense due to the premise where it began which I cite below in quotes.

“So, the huge size of the present-day human population is clearly a major reason why we face so many mounting environmental problems and are now.”

Most of the damage caused to the planet is not humanity’s fault. It is the corporate globalism’s fault. In what straight mind could there be any blame given to a population that has been -from birth- seduced and indoctrianted into believing they are not good enough and that they need to consume in order to exist?

In what straight mind can there be any thoughts to call for depopulation or population control or any other thing of the sort when most of humanity are victims of their own stupidity and decadence? (Deleted personal opinion of other’s motives)

Since this is a one sided forum, let me try to put some perspective. Please visit the Population Research Institute’s website here: http://www.pop.org/ and look at the FACTS. (Deleted personal opinion of other’s motives.)But if you still think population growth is the problem, please do not let me get on the way to helping the Earth survive. Go ahead and start off with yourselves.

LikeLike

@News Desk

(Deleted commen which no longer applies)In fact, this article points out how reducing the population will not solve the climate crisis fast enough and that gradual reduction through education and improvement in living standards is the way to go. It puzzles me how you can infer that BNC advocates a eugenics policy . I suggest you re-read the post fully and carefully before commenting again.

MODERATOR

The original quote, to which you link, has been deleted.

LikeLike

News Desk appears not to have noticed that this site is devoted to two goals, neither of which involves hatred of people.

Goal #1, in my words, is to ensure that our Earth has a climate which is human-friendly. This implies, of course, that the climate must be appropriate to the continuation of all life forms on the planet.

Goal #2, again in my terms, is secondary. Many would agree that current climate trends do not accord with Goal #1 and that energy is the driver. As the lead article here and other articles on this site indicate, the health and enjoyment of humans on Earth are greatly dependant on adequate and reliable energy sources… hence, the great amount of discussion of energy generation options, in all forms in cluding nuclear, on this site.

These objectives are pursued via polite discussion, review of referenced science and fact-based analysis.

News Desk has come here with strongly aggressive and impolite statements about his perceptions. These are, as Perps above stated, incorrect.

Pop.org, the site referred to by News Desk, has strong religious, anti-abortion, right wing political perspectives of population issues. Religion and politics are not part of BNC. Neither have I seen anything on this site (BNC) which those who view the world from News Desk’s perspective could disagree with. Certainly, BNC is not pro-abortion and the aggressive response is not appropriate.

LikeLike

(Deleted inflammatory comment.)

LikeLike

Moderator,

The dig at the right is a bit opportunistic. After all the vast majority of the BNC commenters, including the author of the comment, have strongly left wing views and frequently link to Left wing web sites (ABC, Crickey and a host of others) and promote extreme left views like those of the Greens. However, when any right leaning comment is made, or if an article is linked that ,although a good contribution to the debate, could offend someone from the left, the comment is censored, the link deleted and the commenter chastised. I’m making this point to show that the sort of comments made above are a frequent under-current of Leftist inuendo.

MODERATOR

As previously stated, political attributions not aimed at individuals but at the Party in general are permissible, hence your comment and PB’s stand.

LikeLike

On reflection, I tend to agree with Peter Lang’s comment regarding the use of the term “right wing”. I withdraw it, even though it is a term which is used on the site to describe itself.

I also add another: Climate-science-denying. No need for links – there are plenty of articles listed explicitly in the site’s index to demonstrate that this is true and is fundamental to the site’s purpose.

So, Peter, we can agree again.

Pop.org is not a rational place.

LikeLike

Moderator,

gee. The rules seem to change all the time

JB, Yes we can agree on some things. However, I’d strongly advise dropping terms like “Climate-science-denying”. It is inflamatory, derogatory and intentionally so. It’s as rude as calling someone a fool, and implying hate. It won’t help to achive a concensus on what policies we need to implement to achieve societies requirements and needs. Talk like this has angered 70% of the population and turned them right-off what we need to do.

Using such terms but banning terms like Climate Alarmist, Climate extremist, Left ideologue, etc. shows bias, because some can use derogatry terms like “Denialist” but others cannot respond.

MODERATOR

The rules don’t change. JB attributes the term “climate-science-denying ” to a group who are plainly and openly not accepting the science of climate change. BNC does not allow attacks on individuals or personal opinions regarding other’s motives. Further discussion on this topic is closed.

LikeLike

(Comment deleted as previously warned.)

MODERATOR

As previously stated you may use pro/anti CC/AGW terms, left/right political terms as long as you are describing a group which is clearly and openly labelled by themselves as such. You may not use them when aimed at individuals, where you are assuming that you know their motivations. No ad-hom attacks and no pejoratives please.

LikeLike

(Comment deleted. Off topic and lacking scientific rigour and references.)

MODERATOR

Your personal ideas and cogitations belong on an Open Thread.

LikeLike

Brought here from the storage thread, which I seek not to derail.

For previous comments, see https://bravenewclimate.com/2011/11/13/energy-storage-dt/, for the previous day or three.

——————————-

EL, explaining why he doesn’t trust third world countries to use nuclear power:

What institutional supports, etc, etc? Show me a country which has unreliable, expensive, diesel powered power in its major cities and I’ll show you a country that has poor prospects of population reduction, at least, that is, reduction by means of reduced fertility as against desease, famine or war.

It appears to me to be essential that people living without reliable electricity supplies in the larger towns and cities of the world, perhaps a couple of billion, would benefit greatly if it was available. This applies not only for domestic use, but also for commerce and industry.

Energy, it seems to me, is at the very centre of requirements to lift the status and education of women, which it has been stated above are the surest way to achieve voluntary reductions in fertility. (See, for example, Barry Brook, on 21 September 2011 at 2:41 PM: “The fundamental point… is not that we ought to do nothing about population size. [I]ncreasing affluence/education of women seems to be the most effective measure.”)

Unlike some, I advocate nuclear power, especially the almost-available smaller buried package plant in the 40 – 60MW range, as reasonable sources of this electricity. They are essentially set-and-forget zero enrichment, zero waste storage, highly secure and reliable. Want to get heaps of value from your foreign aid dollars? Spend some by providing basic energy where it is needed and earn the spinoff benefit of providing carbon without carbon.

What’s not to like about that?

A no- or low-electricity approach to towns of tens of thousands, let alone cities of millions, is doomed to produce more refugees, more hardship and to leave billions reliant on dung and fossil oil and gas for cooking. It is as plain as day that it cannot work.

Locking in fossil fuel and dung for cooking locks in risks due to air pollution in the home and outdoors, of severe burns which are common where gas and kero are used for cooking, and it locks in poverty due to the increasing prices and impending world shortage of these fuels. Without mains electricity in centres of population, the conditions for low fertility rates simply don’t exist, so this must be #1 priority of aid programs.

To argue, as EL has done, that the recipient nations are not fit to use nuclear power for security and other reasons, is paternalistic and unacceptable. The risks posed to the population from package NPP’s, or even India’s Jaitapur Nuclear Power Project are much lower in the domestic sense than the existing situation, in addition to which proper power supplies allow commerce, trade and industry to grow.

Yet Jaitapur faces challenges and tactics which are straight out of the American anti-nuclear power scare playbook and which are incited and supported by Greenpeace and other Western organisations which take access to reliable and abundant electricity in their homes and places of work for granted.

It is appropriate for those who advocate denying access to mains power to up to half of the world’s population to explain their vision for social stability and education and quality of life, especially for women, which have been demonstrated in this thread to be essential precursors for reduced birthrates.

LikeLike

Since I’m in a particularly cheerful mood tonight, here’s The Onion being proactive on population:

Scientists: ‘Look, One-Third Of The Human Race Has To Die For Civilization To Be Sustainable, So How Do We Want To Do This?’

LikeLike

[…] mark, excluding a Children of Men fertility scenario. This was discussed a little while ago at Brave New Climate. The UN says […]

LikeLike

[…] philosophy might imply. Things like developing nuclear power in favour of coal, how to deal with over-population and providing enough food for humanity now and into the heated future, are all contentious issues. […]

LikeLike

[…] https://bravenewclimate.com/2011/09/19/population-no-cc-fix-p1/ […]

LikeLike

[…] BNC readers will be amused to know that it was based on a BNC blog I did on population and climate a few years ago. https://bravenewclimate.com/2011/09/19/population-no-cc-fix-p1 […]

LikeLike

Population cannot be addressed in isolation. Other factors, such as per capita consumption are equally important. We know today that we’re consuming our ecosystem’s renewable resources at just over 1.5-times their replenishment rate. That is worsening by the year. Some aspects of it such as deforestation, desertification, dry lakes and rivers that no longer flow to the sea are visible to the naked eye from the ISS. Satellites monitor surface subsidence caused by aquifers drained for agriculture and other purposes. We monitor the collapse of global fisheries and new research shows our devastating impact on dwindling biodiversity.

India, China and other emerging economic powers are producing very large, ‘consumer class’ populations demanding more and better everything from houses to cars to meat-based diets.

Climate change, overpopulation and over-consumption intertwine. They present common challenges that speak to common solutions.

LikeLike