This is Part II of the “Sustaining the Wind” series of essays by David Jones. For Part I, click here.

This is Part II of the “Sustaining the Wind” series of essays by David Jones. For Part I, click here.

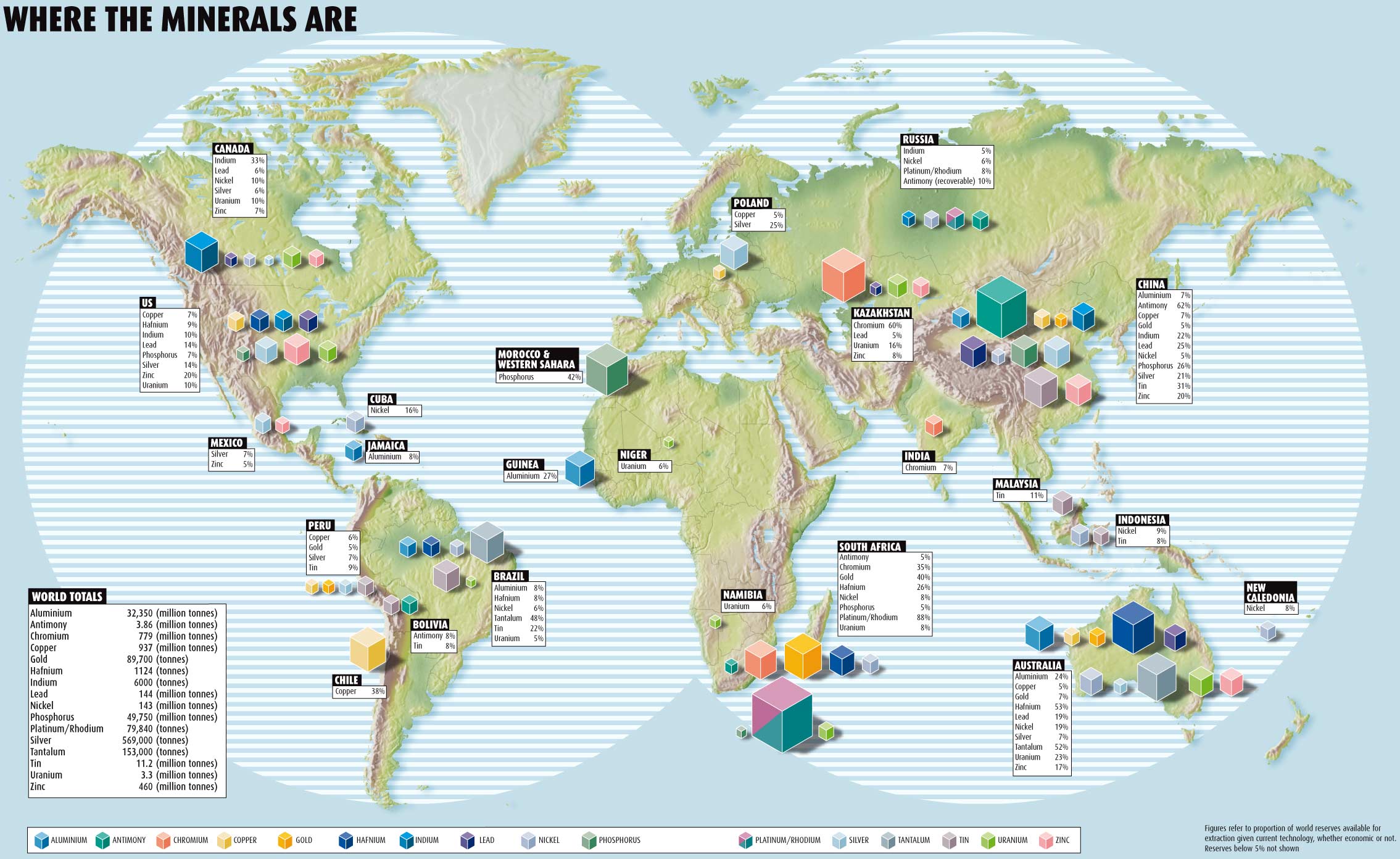

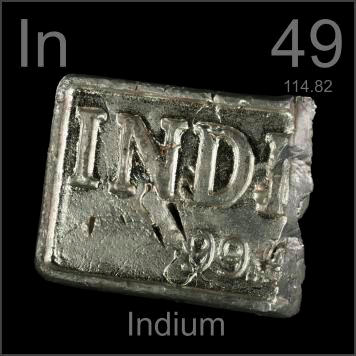

At the conclusion of part 1[i] of this series, we saw that the putative demand for the element indium in order to build some 15,000,000 wind turbines (at a nominal peak capacity of roughly 900 MW) that would be required to produce annual outputs of 90 exajoules of energy, given the low capacity utilization associated with wind infrastructure, was on the order of 18,000 tons. Although predictions about the total geological supply of any element or mineral are inherently fuzzy, we have also seen that if true, it is quite possible, that the indium demand for wind power alone, never mind the solar industry where it is a key constituent of “CIGS” (copper-indium-gallium-selenide) thin film solar cells, might well exceed the geologically available reserves of the element. In this part we will look at indium as a surrogate for the many critical elements on which modern technology depends. We noted in part 1 that a consideration demand for the elements and minerals required to construct so called “renewable energy” infrastructure is one to two orders of magnitude higher than the demand required to construct nuclear power plants. Moreover we examined data connected with the Danish database of commissioned and decommissioned wind turbines to determine that historically wind turbines remain operational of a mean period of about 15 years – with some capacity lasting a little longer than 30 years, and some for less than two years – and thus efforts to expand wind capacity – which now produces less than 2 exajoules of the more than 560 exajoules of energy humanity consumes – will involve not only adding massive new infrastructure, but also regularly replacing worn out capacity.

As we look at indium, we will not assert that the wind industry is completely dependent on access to it. It is always possible that replacements can be found for any material, as we will see, but we will nevertheless show that the game of “material musical chairs” if you will, is a profound challenge, and that often the hand waving and wishful thinking that surrounds issues in energy, especially where so called “renewable energy” is concerned, is at best glib, at worst misinformed to the point of delusion. The fate of humanity is very much dependent on the decisions we will make in this century; possibly no generation has faced such a demand for clear thinking as the immediately coming generations will face, even as the current generation has failed the future miserably.