Guest Post by Graham Palmer. Graham recently published the book “Energy in Australia: Peak Oil, Solar Power, and Asia’s Economic Growth” (“Springer Briefs in Energy” series).

Guest Post by Graham Palmer. Graham recently published the book “Energy in Australia: Peak Oil, Solar Power, and Asia’s Economic Growth” (“Springer Briefs in Energy” series).

The Tesla Powerwall is promised as the critical third key to unlocking the Tesla Triumvirate – solar, batteries and electric vehicles. The Powerwall provides an opportunity to look at the opportunities and weaknesses of distributed power, and examine the long-run sustainability of such a system. To do this, we can turn to life-cycle assessments and the field of Energy Return on Investment (EROI).

EROI is the ratio of how much energy is gained from an energy production process compared to how much of that energy is required to extract, grow, or get a new unit of energy. Advocates of EROI believe that it offers insights about energy transitions in ways that markets can not. The availability of surplus energy has been one of the main drivers of economic and social development since the industrial revolution.

At the start of the 1990’s, Pimentel launched a debate that was to be long running, on the effectiveness of corn ethanol production in the United States. Pimentel drew attention to the energy intensity of the ethanol life cycle, including nitrogen fertilizer, irrigation, embodied energy of machinery, drying, on-farm diesel, processing, etc. Although not settled decisively, there is a consensus that the EROI of US corn ethanol is below the minimum useful threshold. Brazilian ethanol seems to be better, and there is hope that second generation biofuels will be better again.

The relative fraction of residential energy end-use in Australia helps to give a sense of the scale between our direct household energy use, and the total energy consumption in Australia – according to the Bureau of Resources and Energy Economics (table 3.4), residential energy consumption made up 11% of total energy consumption, with electricity a little under half of that. As a community, the vast majority of our energy footprint is embedded in the goods, food, products, and services that we consume.

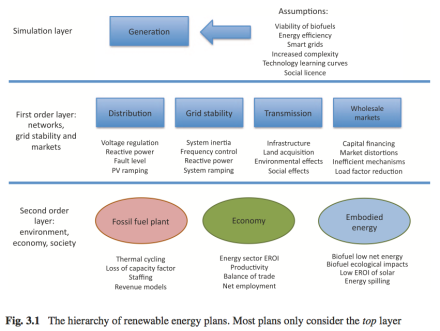

We can also apply EROI principles to electricity production. However electricity is only valuable within the context of a system and isolating the EROI of individual components is more challenging. We can, however apply life-cycle inventories to individual components, including solar, batteries, and electric vehicles, and see how they perform. Life-cycle assessments measure the lifetime environmental impacts of greenhouse emissions, embodied energy, ozone depletion, particulates, water and marine toxicity and eutrophication, and other effects.

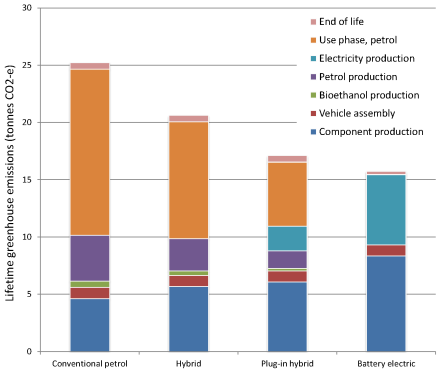

The UK-based Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership compared a range of low emission vehicle options in the UK. This considered the full life-cycle of the vehicle including production of the vehicle with a driving range of 150,000km. The conventional vehicle was based on the VW Golf, and the electric vehicle was based on the Nissan Leaf.

Based on the current European grid, it concluded that EVs generally have lower life-cycle emissions than an equivalent petrol vehicle, but the outcome is dependent on the electricity grid and other factors. The report also projected the analysis out to 2030, assuming improvements in energy and vehicle technologies. For the ‘typical 2030’ scenario, the emission intensity of the UK and European grid was assumed to drop to between 0.287 and 0.352 kg CO2-e/kWh (around a third of Australia’s current emission intensity).

The most important outcome of these life cycle assessments is that the embodied energy of the battery and the emission intensity of the grid are the crucial determinants of the emission intensity of EVs. The report assumed a battery capacity of 24 kWh for the EV, or less than a third of the Tesla Model S battery.

Pick up a research paper on battery technology, fuel cells, energy storage technologies or any of the advanced materials science used in these fields, and you will likely find somewhere in the introductory paragraphs a throwaway line about its application to the storage of renewable energy. Energy storage makes sense for enabling a transition away from fossil fuels to more intermittent sources like wind and solar, and the storage problem presents a meaningful challenge for chemists and materials scientists… Or does it?

Pick up a research paper on battery technology, fuel cells, energy storage technologies or any of the advanced materials science used in these fields, and you will likely find somewhere in the introductory paragraphs a throwaway line about its application to the storage of renewable energy. Energy storage makes sense for enabling a transition away from fossil fuels to more intermittent sources like wind and solar, and the storage problem presents a meaningful challenge for chemists and materials scientists… Or does it?

Guest Post by

Guest Post by