Guest Post by Ben Heard. Ben is Director of Adelaide-based advisory firm ThinkClimate Consulting, a Masters graduate of Monash University in Corporate Environmental Sustainability, and a member of the TIA Environmental and Sustainability Action Committee. After several years with major consulting firms, Ben founded ThinkClimate and has since assisted a range of government, private and not-for profit organisations to measure, manage and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions and move towards more sustainable operations. Ben publishes regular articles aimed at challenging thinking and perceptions related to climate change at www.thinkclimateconsulting.com.au.

(Editorial Note: [Barry Brook]: Ben is a relatively recent, but very welcome friend of mine, who is as passionate as I am about mitigating climate change. I really appreciate publishing his thoughts in this most difficult of times. Now, more than ever, we must stand up for what we believe is right]

Update: This is a revision of an earlier post from ThinkClimate, reflecting the useful contributions of BNC readers, the evolving situation in Japan, and focussing on the broader message regarding our future decision making in energy

—————————-

On 8th March, I delivered a presentation to around 45 people, describing my journey from a position of nuclear power opponent to that of nuclear power proponent. This journey has taken me around three years. The goal of my presentation was to foster healthy discussion of the potential future role of nuclear power in Australia, a nation with among the highest per capita greenhouse gas emissions in the world. The presentation was very well received and has generated much interest.

Just four days later, I saw those first appalling images of the tsunami hitting Japan, and realised that for the first time since 1986, a nuclear emergency situation was unfolding.

In all cases, I find it most distasteful when individuals or groups push agendas in the face of unfolding tragedy. Let me say at the outset that this is not my intention.

Sadly, many people and groups don’t share this sentiment, including a great many who have wasted no time in making grave and unfounded pronouncements regarding the safety of nuclear power, and how this event should impact Australia’s decision making in energy. This has been aided no end by a media bloc that has reflected the general state of ignorance that exists regarding nuclear power, as well as a preference for headlines ahead of sound information at this critical time. The whole situation has been all too predictable, but still most disappointing. It has reinforced one of the great truisms in understanding how we humans deal with risk: We are outraged and hyper-fearful of that which we do not understand, rather than that which is likely to do us harm. Rarely if ever are they the same thing.

Those who attended my presentation on the 8th March will have seen that I place a high value on two things in forming an opinion and making a decision: Facts and context. Facts without context can be dangerously misleading. In this article therefore, I would like to present some of the basic facts and context of this event, as well as providing links to reliable and up-to-date sources of information to gain a more detailed understanding of the crisis. From there, I only ask that you maintain a critical frame of mind in considering the implications of this event for national and global energy supply.

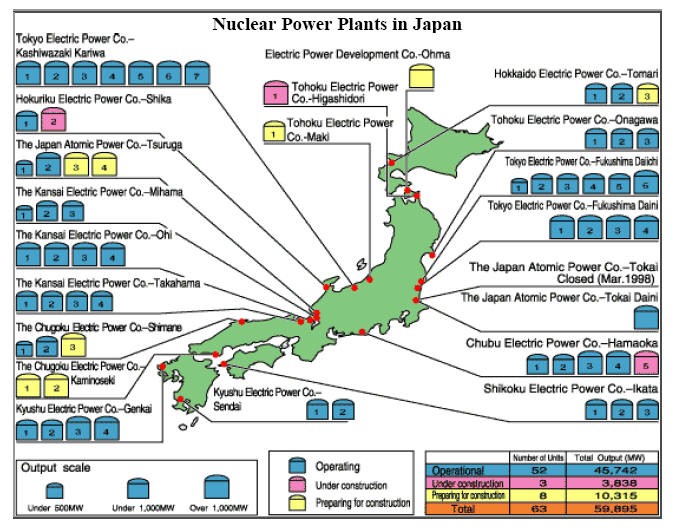

Firstly, the context. Japan is a densely populated chain of islands. It is the fourth largest economy in the world, and derives around 30% of its electricity from from 55 nuclear reactors at 17 locations around the country. Japan has been using nuclear power for some time. As such some of the reactors are approaching 40 years of age. They are older designs (Generation 2) in comparison with what can be built today (Generation 3+ or Generation 3++).

On 11th March, Japan experienced an earthquake in near Sendai measuring 9.0 on the Richter Scale. The Richter Scale is logarithmic, meaning a 9 quake is ten times more powerful than an 8, 100 times more powerful than a 7 and so on. Prior to this event the United States Geological Survey had only 6 recorded earthquakes of 9.0 or greater. While Richter Scale measures total energy of a quake, another other key measure of severity of an earthquake, often more relevant for human impacts, is peak ground acceleration (PGA). In this case it appears the Sendai quake was moderate, with PGA of around 0.5. This compares with the recent Christchurch quake, with a smaller Richter Scale value, but a much higher PGA of 2.2. Taken together, we can safely say that this quake was moderate to severe.

However, just one hour later, a tsunami measuring up to 10 metres struck large parts of the Japanese coast. We have all seen the awesome and terrifying footage of this wave, which laid waste to nearly everything in its path. This gives us a final and tragic element of context, being the greater tragedy unfolding in Japan. This catastrophe is likely to have caused fatalities in the 10,000s, and left great areas of the country in total wreck and ruin.

So by way of context, what I would like you to do is take an island nation with high population density and extensive coastal geography. Then overlay a high penetration of nuclear energy, with multiple reactors, in multiple locations, including some approaching end of life. Then overlay a two-phase natural catastrophe, with only one hour between each phase. The first phase is moderate to severe, and the second phase is catastrophic.

I am sure those of you who have ever conducted risk assessment exercises will agree that even if the job was to think worst case, it would be difficult to construct a scenario that would pose a more comprehensive and arduous test of the operational safety of nuclear power plants in the world today. That doesn’t mean this was completely unforeseeable, nor that better plans were not possible. But risk assessment means examining the interaction of multiple, relevant criteria. Altering some or all of the factors described above would change the baseline risk. For example, envisage a more severe quake, but in a more thinly populated nation. Depending on the extent to which you alter each factor, the overall risk of human harm could go up, or it could go down.

My assessment is that with all criteria taken together, the events unfolding in Japan represent quite an extraordinarily severe test of the operational safety of global nuclear power in 2011.

Let’s now turn to the response of Japan’s nuclear power plants to this event, sticking at this stage, as best I can, to high level facts that are not in dispute:

- When the earthquakes struck, Japan’s nuclear power stations did as they were designed to do and shut down with the insertion of control rods. This halted the nuclear chain reaction that generates the power. In response the plants rapidly dropped in power to around 5% of normal.

- Other (non-uranium) constituents of the fuel remained “hot” i.e. reacting, which is normal.

- Back up power systems (diesel generators) were introduced to continue to provide cooling to the reactor core. This worked as expected.

- Approximately 1 hour later, two power plants housing seven nuclear reactors were struck by a 7 metre tsunami. The plants in question were Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Daini. These are Generation 2 Boiling Water Reactors (BWRs), each have been in operation for around 40 years.

- The tsunami disabled the diesel generators that were in use, and all other back-up generators that were available. It is this second disaster that triggered the problems at these power plants, as the plants began to experience a loss of cooling on the fuel.

- Back-up cooling from batteries was applied, and provided cooling for approximately a further 8 hours

- Other measures have then needed to be implemented as this power source ran out. This has included pumping sea-water into the reactor core. This is not a preferred action as it causes some damage.

There now appears to be a cascade of difficulties as a result of this loss of power. Controlled venting of radioactive gas has led to explosions as hydrogen levels have elevated. These explosions have caused injuries and resulted in further damage to some parts of the reactors, increasing the scale of this emergency. While most of the reactors have been brought to a safe condition, dangers remain. Some spent fuel, that has been used already, but needs to be cooled off for a few years before being moved to dry storage, appears to have becomes exposed. Again, the loss of power has created a concern here, and there are high levels of radioactivity near one of the pools. The impact is a local one; they are solid fuel rods, and the radioactivity is not easily dispersed as it is with a gas. But it is making the job of bringing things under control much harder. The incident has received a severity rating of INES 6. It is clearly very serious. The Three Mile Island Accident was a 5. Chernobyl, however, was a 7 (the highest), and is a very different league

For more detailed and technical information regarding these events, please go straight to www.bravenewclimate.com.au and follow the daily updates and review some of the other excellent, more technical postings

There seems to be some suggestion that “but for the efforts” of the engineers, this situation would be worse. Well, that’s true, but at the same time, misleading. Passive safety is a great thing, be it nuclear power plants or the cars we drive. But at the end of the day, a key control measure in catastrophic events will always be a skilled and well trained work force with the knowledge and ability to respond to a changing situation. That’s as true for the power plants as for the rest of the country, where the army, police and other emergency services will play a vital role in mitigating the damage.

At present, the events at Fukushima have not resulted in any deaths attributable to nuclear power. The eventual impact of the releases of radiation to the environment cannot be known at this time, but most of the dispersed radiation, that has come as a gas, is likely to be very short lived . There has been a major evacuation, which has no doubt been highly distressing for all involved and entails risks of its own. But it was a wise procedure that stayed a step ahead of the difficulties at the power station. Injuries have been minimal in the context of this catastrophe (about a dozen related to the hydrogen explosions). The situation for the workers has certainly become riskier with elevated levels of radiation from the cooling pond and the larger releases of radioactive gas and this situation remains live. 8 — 10 of Japan’s 55 nuclear reactors are known to have varying levels of damage that will impact their ability to provide electricity. The remainder will no doubt require inspection, but would appear to be relatively undamaged.

So, combining the extraordinary context with that high level summary of facts, what early conclusion might be drawn about the current and future role of nuclear power, particularly with regard to operational safety? Do we remain open to talking about nuclear power, or shut ourselves from that discussion? What do we do as a globe, riding a warming trajectory that ends in utter catastrophe, yet still hunting down and burning fossil fuels, liquidating lives as we go and polluting our air with soot, sulphur, and greenhouse gas? What do we do when nuclear power frightens us so much but, compared to other energy sources, harms us so little? What do we do in Australia, where we have never trod the nuclear path, remaining steadfastly at the teat of coal, with a clean state to transition to the very best nuclear technology? What about in rapidly developing nations, hungry for energy to bring their people out of poverty and under pressure to reign in greenhouse gas emissions? What about those developed nations with high levels of nuclear already, who could only return to fossil fuels to meet the demand?

It is up to each of you to answer those questions, and I don’t want to push an agenda. If you want my conclusion, read on.

We are witnessing the third severe incident in the 50 year history of the nuclear power industry, an industry which now has over 14,000 reactor years of experience. An extensive nuclear power sector, including some 40 year old reactors, in a densely populated nation has been tested by a catastrophic natural calamity. To date, two power stations of older design have experienced very serious emergencies, but contributed no deaths, minimal injuries in the context of the catastrophe, and environmental impacts that will likely be transitory and local. The nuclear power industry can, must, and will learn crucial lessons to further mitigate against such an emergency. But the history of the industry and the outcomes of this event so far suggest to me that, at their most basic, nuclear power stations must be among the sturdiest and least dangerous infrastructure in the world. And in a world that is quickly cooking itself through climate change, informed discussion on nuclear power must not be allowed to suffer from the hype, headlines and hyperbole that have stemmed from this tragic event.

Fear or facts. I choose facts. I hope you do too.

Filed under: Clim Ch Q&A, Future, Nuclear

.png)

Thank you for this excellent summary post at this time.

The events of recent days have not changed the choices we have available to address the challenge of climate change. And they have not changed the desiderata around our possible courses of action, which remain now as they were on thursday.

The impacts of climate change truly pose an existential threat. Nuclear power, as we are seeing today, does not. It is the fastest and most effective tool we have available to decarbonize our energy system, and our wisest course is to do so as rapidly as possible.

Thankyou Ben for this excellent post. I hope you don’t have to put up with the level of venom and spite that has been directed towards Barry for his honest appraisal of the unfolding crisis. Quite honestly I wouldn’t blame him if he shut the door here and concentrated on his academic research. This is not his day job and I know he devotes many hours of his own time to this blog often into the early hours and on weekends. He is a young man with a family and deserves some time off to enjoy his personal life.Those of us who know him can vouch for his honesty, integrity and dedication to scientific rigour. Keep up the good work Barry.

The situation has now officially escalated to INES Level 6, according to Japanese officials (see NHK).

An update may be in order…

Thank you, John, Ms Perps. And I share your thoughts regarding the effort Barry is expending doing this important job. Bob, thank you, let’s look at what this means and the updates that need to be made. And lets remember: Context, context, context. There is no other way to make the hard decisions.

I too thank you! — for your voice of sanity, honesty and, I believe, the true facts here.. I am indeed no scientist, but ever since my reading of Tom Blees’ extraordinary book (“Prescription for the Planet”) have become an intensive reader of “Brave New Climate”, and, after years as an actively anti-nuclear person, have become decidedly “PRO” — in particular, of course, re the new designs yet tocome…

Thank you Ben. The issue at hand here is risk. And if we are to consider risk related to those energy sources able to generate base load power over the long term, we must include the only other one able to tick both those boxes… coal.

A different type of risk, of course, but far greater in a global sense and something that should prompt us to think about the admittedly terrible events at the Japanese power stations in the context of the real Big Picture.

I also hope Ben is not subjected to venom. Serious critical discussion, though, I would hope is welcomed by everyone.

I agree with Ben that the Japanese reactors have performed extremely well in preventing a massive release of radioactivity following a major natural disaster.

The problem, however, is that most Japanese people will understandably wish to know why they should be facing any risk of radiation damage to add to their list of woes. Is it not enough that entire towns have been levelled, that now they should face the prospect of ongoing health damage as well? These are the understandable concerns that will drive the anti-nuclear rhetoric in the next weeks.

Ben does not address the medical or ecological outcomes of this disaster, other than to say that only a handful of people have been injured at the plant. That is true as of yesterday, but they were measuring up to 400mSv/hr at the plant today, with winds blowing inland and a fire in reactor 4. These are immediate threats to health that cannot be lightly dismissed even before the longer-term consequences are considered.

For those living 30km from Fukushima, who have been told to stay indoors to avoid fallout, I think the “zero deaths” and “no significant or lasting environmental impact whatever” that Ben asserts would seem to be premature to say the least.

Let us all hope that he turns out to be right, and that nobody will be exposed to damaging levels of radiation. Even in this now unlikely scenario, I would sympathize with any Japanese residents who now decide to campagn vigorously to reduce the possibility of this kind of scare happening again. If they say “energy prices be as they may, my children should not grow up in fear”, who can blame them?

When you state that there has only been four category nine earth quakes in recorded history this context does change my thinking in one regard. I had pondered why the design rating of these plants was only based on a category 8.2 event. It seems clearer now given your context (assuming it’s accurate) why this may have been the case. We are it seems dealing with a black swan type event.

One piece of context that would be very useful to understand better in terms of energy security, especially given the recovery effort that now awaits, is the percent of total electricity production capacity that has now been lost due to the earthquake and tsunami and the proportion of this loss that can be attributed to nuclear. It sounds like the vast bulk of the nuclear capacity will be operational again quite soon and yet there is talk about shortages. This suggests that there has been some loss of capacity in other electricity generating technologies (eg coal plants). Although obviously damaged transmission probably accounts for some of the problems also. It would be good to get a handle on the relative proportions.

Following the recent INES rating update, the final bullet point in this post was modified and brought up to date. The theme of this post was the interrelated importance of facts and context, as well as the need for all concerned to weigh up both to form their own, informed conclusion. The changed rating is a fact, so no one should shy away from it, and I do feel for those responsible for this worsened situation. My reading of the facts and context together(which touched just barely on the actual issue of climate change) leaves my conclusion very much in tact and unchanged.

Before I sign off, let’s have a few more shout outs to Barry , Ms Perps style . His effort has been gargantuan these last few days, and the extra 1/2 million hits this site has received in just a week goes to show just how many people turn to him for good, factual analysis. And if you disagree, keep it in the professional spirit of the blog.

A valuable and timely contribution. Following.

TerjeP, I had that thought as well – what’s the situation with Japan’s coal-fired power plants in the quake & tsunami zone?

Certainly a 9.0 is a phenomenal quake. I’m amazed at how well much of the Japanese infrastructure & buildings have stood up to it, although pics of quake damage are few & far between, being overwhelmed by imagery of tsunami damage.

This may be useful in allaying radiation fears:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/mar/15/japan-nuclear-crisis-tsunami-live?commentpage=all#start-of-comments#block-57

And the spreadsheet:

https://spreadsheets.google.com/lv?key=tgXu86sAcSkqNVbyCooH_Bw&toomany=true#gid=0

I read often that with a magnitude 9.0 earthquake the occured damage is not surprising.

Regarding he impact of the magnitude 9.0 earthquake:

It should be considered, that the measured peak ground acceleration (PGA) at the coast in Japan (about 0.25 g) was lower than at the earthquake in Christchurch February 21st, with magnitude 6.8, where PGA of up to 2.2 g occured.

Magnitude alone is not the measure to take for this incident and is not necessarily sufficient to justify the damage.

Considering that, I hope that the tsunami caused the main reason for the damages at the reactor system. Otherwise earthquake safety of nuclear power plants has to be viewed from a new point…

Following

This blog has been interesting, but I wish you guys would acknowledge some of the easy-to-fix design flaws:

(1) Why was this particular plant only designed for a 23 foot Tsunami? Why not put it at an elevation of at least 70 feet above sea level?

(2) Is it necessary to build so many reactors (6) so close to each other?

(3) Why is spent fuel stored in the same building as the reactors?

(4) Why are 40-year-old plants still on-line?

All of the above could have been fixed with more money and we wouldn’t even be having this discussion. It’s the greed of the plant owners that got us here.

Maintaining credibility can be a tricky balancing act. Looking around the net I think plenty of pro-nuclear peope have made a mistake with this balancing act. It is quite understandable that you want to dispel some of the myths, the scaremongering, the sloppiness in the media. All fine & good. But it is quite easy to seriously overcook the reassuring words, and this causes problems with credibility when the situation moves on and things turn out to be worse. There are clear signs that this has happened in this case. In my opinion those who want to reach out and help lots of people to get a balanced view of nuclear, should not repeat these mistakes again – where there is a lack of trust in what the industry and its friends tell the public, you need to try to meet the public in the middle. This means not dismissing all the fears in such a total and complete way, a way that leaves you with less wiggle room if the situation deteriorates. Even if a lot of the fears people have are irrational, and it gets frustrating, resist the temptation to make reassuring noises at too high a volume, in order to preserve some credibility for the long road ahead.

Not to flog a dead horse, but I’m still thinking about the injection of seawater. Won’t there be neutron capture by the sodium atoms (particularly in Unit 3) resulting in highly radioactive seawater?

-bks

bks, there will be some activation, but the half-life of Na24 is only 15 hours.

While you certainly have some valid points, some of your reassurances are way too strong given an ongoing situation with new explosions, fires, exposure of fuel rods etc. continuing.

In particular:

There are numerous reports that the containment vessel of reactor #2 has indeed been breached. Maybe that’s wrong, but your categorical statement to the contrary doesn’t seem justified.

The fire in unit #4 apparently released significant radiation to the environment, presumably from the spent fuel rods stored there. There are reports that the temperature is rising in the storage pools of several units and that the storage pool of unit #2 is boiling. Again, that may be wrong but categorically stating that things are under control seems an overstatement.

Excellent perspective. Let’s hope and pray we’ve already heard the worst. I’ll pass a link along to others.

Ron P.

[…] This site seems to have a good timeline and breakdown of the problems that lead to the current situation with the nuclear reactors that are having issues. It’s an interesting read. […]

The big fear is whatever anyone believes a “meltdown” is. People are being told in the US by mainstream media that 1 million people died as a result of Chernobyl. MSN’s headline, served up to Blackberry subscribers this morning was “Panic in Tokyo”.

I find it impossible to find fault in what Barry is trying to do in the face of absolutely irresponsible reporting like this.

“WASHINGTON — A U.S. nuclear industry official says there is evidence that the primary containment structure at one of the stricken Japanese reactors has been breached, raising the risk of further release of radioactive material.

Anthony Pietrangelo of the Nuclear Energy Institute said Tuesday that falling pressure inside the suppression pool at the No. 2 reactor at Fukushima Dai-ichi and reports of rising radiation levels there raise the possibility that the reactor’s containment has been breached. He said the breach of the primary containment structure could lead to the release of more radioactive materials.”

http://www.seattlepi.com/national/1110ap_us_japan_earthquake_nuclear_briefing.html

-bks

Attention all media bashers. You might want to take note of two items in this morning’s NY Times.

(1) On the front page of the Business section:

“Energy Needs Sustain Nuclear Push: India and China Move Ahead While Advanced Nations Back Off”

(2) From the lead editorial:

“This page has endorsed nuclear power as one tool to head off global warming. We suspect that, when all the evidence is in from Japan, it will remain a valuable tool. But the public needs to know that it is a safe one.”

Possible grounds for cautious optimism.

Steve Elbows’ comments are excellent and need to be taken to heart. The situation is still unfolding, and honestly no one should be making any pronouncements about what should or should not be done going forward until there is more understanding of the situation and what exactly went wrong with what. Something more serious than just a loss of outside electric power happened here, and every time I hear, “well the worst would be…” and it is exceeded, it makes me feel that we really don’t understand the true possibilities for various failures at all. In particular, I suggest that using the phrase “zero deaths have resulted from radiation” at this time is horribly premature.

I praise the various powers that be for recognizing that the plants would have to be scuttled and using seawater and other options to get the situation under control. I wonder if they would have been as aggressive to do so had the plants been 4 years old instead of 40. We need to be extremely careful about setting up situations where a private entity gets all the profit if everything goes perfectly, but society at large takes all the risk (both financial and physical) if something goes wrong.

A more balanced view would be, “Of course we are very concerned about what we are seeing, and we will take all measures necessary to understand what happened and to change our designs and procedures in light of what we are learning from this unprecedented situation.” That would be much more reassuring than, “We re-read the 15 year old licensing application and it says right there that the designers thought about earthquakes.”

(First of all, big Respect to Barry. You’re steering a very difficult course with commendable aplomb, and you’re in my thoughts and prayers at this time.)

We ought to draw some reassurance from the state of the Onagawa nuclear plant. This was considerably closer to the epicentre than Fukushima Daiichi, but being somewhat more modern (BWR units commissioned 1984/1985-2002) they rode out the quake and tsunami with no apparent major problems.

There is a good BBC clip “Japan’s radiation risk explained” here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-pacific-12744973 . This guy (Prof. Paddy Regan) gives a nice visual demonstration.

[…] here and here. Iain recommends the Brave New Climate blog for continuing coverage. As we write, the lead blog post is from Ben Heard, director of the Adelaide-based advisory firm ThinkClimate Consulting. Heard comments: In all […]

I know it won’t matter to regulars here, but aren’t you even slightly concerned that reality will continue to veer off your optimistic gameplan?

To wit:

“Zero release of radiation levels of a danger to human health, except for brief periods for those working within the plant compound (not Public exposure). These workers would be well protected and monitored to avoid excessive accumulated doses”

Zero release! (seriously?)

Given that only about 50 workers remain on site (out of 800? originally) and 3 reactors are mid-meltdown, plus fuel-rod cooling ponds at these and other reactors are not functioning properly, isn’t there a chance that some of those workers will recieve an unhealthy (or as you put it “excessive accumulated”) dose of radiation?

disdaniel comment #23 on 16 March 2011 at 3:50 AM said:

“I know it won’t matter to the regulars here, but aren’t you even slightly concerned that reality will continue to veer off your optimistic gameplan?”

I think the problem is many you’ve been listening to “fear mongering” media and if you have no background knowledge of science you tend to accept their version of things because fear shuts down critical thinking. Remember how the Bush administration used fear to get people and lawmakers to do what they want?

If you have some relevant science background you are immune to that type of scare tactic and therefor make rational decisions. So contrary to your belief that people here are “drinking the Kool-Aid” it’s not them it’s you. I’m not saying that to be condescending cause I’m not an expert either but I do have enough of a background to see the logic in the posts here and the illogic in the hyped fear mongering media.

Another thing is that if you fall into the “fear” trap you may be thinking in one dimensional terms. That might constrain your thinking into a linear set of possibilities set by “fear mongers” where the possible events given to you have to fall between 2 options or somewhere in between and you are led to believe the situation has to be somewhere on that line.

I think, at least for me and again I’m not an expert, if you understand some of the science behind what’s going on it’s like running a simulation in your head where you can see if you take action A,B,C it will result in outcome X and if you take actions D,E,F it will result in outcome y, etc. I guess I would call that multidimensional thinking.

Don’t know how the real experts describe their mental model of it though.

@fred:

In answer to your questions:

1) The height of tsunami’s is a direct correlation to the strength, duration and type of ground-shaking in an earthquake. Therefore, the design height of the seawall and location of it were a function of the design earthquake of 8.2. If the design earthquake had been 9.0, the seawall height/location above sea level would have been different.

2)Building reactors together in groups is industry standard practice for a number of reasons. Siting of nuclear plants is difficult at best so when you get permits you tend to take advantage. Next is construction management. Finally, ongoing management of fuel – delivery, and storage is easier to manage on one site than spread out over even more locations then there already are.

3)This one baffles me as well. There is a ground-level common storage pool at the Daiichi site as well as several of these airborne pools in each reactor building. In the case of reactor #4 which is fueled with MOX fuel – I can see the need to keep it separate from the other fuel. But four stories off the ground above the reactor – that is puzzling.

4)40-year-old plants are still on line everywhere – including here. The Vermont Yankee plant in Maine is an identical design and age to these and it has been in the news recently due to radiation leaks into the groundwater. Its license was just extended for another 20 years.

The Japanese plants at Daini and Daiichi were in the process of being decommissioned. Daini #4 was already shut down. Daiichi #5 and #6 were shut down. Daiichi #4 had just started that process. Daiichi #3 was scheduled to begin the process in just a few weeks. The rest of the reactors at both these sites were all scheduled to be off-line and de-comm’ed within the next five years.

Nuclear plants are very expensive to build and to maintain. Even the ones that are de-comm’ed must still keep their spent fuel storage since there is no place to put it. The lifespan of a nuclear plant is a function of finances – trying to recoup your investment. It actually probably never happens.

Japan has the additional problem of not having any of its own natural resources and has to buy all of the stuff it needs to provide energy/power for its people and its economy. This puts them into a position that almost no other country in the world is in and also goes a way towards answering the question of why, with their experience with nuclear – they would even consider using it for any reason given the risks.

And the actual failure here was not the reactor, or its containment. It was the seawall and the backup generator. It was a failure of redundant ‘normal’ infrastructure, not of specialized, “risky” nuclear power reactor structures.

disdaniel,:

You quoted a sentence but then ridiculed two words in it out of context? Seriously? I mean I think it would be an obviously pathetic ploy even to the neutral observers you are presumably trying to influence.

Fred:

The standards are what they are, reflecting the regulators balance of benefit to risk. I’d guess the spent fuel pools are close to the reactor to minimize moves of radiologically hot fuel. That may change of course.

How exactly has the “greed of the plant owners got us here”?

“If you have some relevant science background you are immune to that type of scare tactic and therefor make rational decisions.”

I see. Wasn’t it the people with the relevant science background that designed, built, and operated and are furiously trying to contain the damage to Japan?

Given that this is a dynamic situation, fear or no fear, I find it astonishing that someone would assert “Zero release” at this point in what I would assume-based on prior posts here-is already much worse than the worst-case envisioned here just 2-3 days ago.

“fear shuts down critical thinking”

I agree! I actually came here looking for a different perspective, and to gather additional facts. What I found appears to be a different universe…and a surprising lack of critical thinking.

To wit: are any of you questioning what if things (anything at all) are worse(!) than TEPCO has publicly admitted/stated? Given that TEPCO has a strong financial interest in downplaying the incident. I see no skepticism here…strange given what is known about TEPCO (indeed any organization) in a tragic & fast moving event like this.

Joffan

I quoted the entire bullet point. How is that taking anything out of context?

@ Steve Elbows – you state my concern better than I did in some earlier posts…moderation of definitive conclusions in the face of rapidly changing events is always a good idea. Especially when one is in the position of an expert making a case on a topic prone to misinformation and passionate opinions (such as nuclear power). We live in a media world where far too many opinions are treated as fact.

Credit to Dr Brook and Mr. Heard for continuing to try and educate the public about the facts related to nuclear power. Reason and facts are the way forward for debates about both climate change and possible solutions, whether nuclear or otherwise.

It is from that position (as a fan of reason and facts…not for any other agenda) that I still have concerns that supporters of a nuclear power future are being too rosy about future possible outcomes of this ongoing incident as they comment on it in real-time.

For example, from Mr. Heard’s otherwise excellent post, comments like “bottom line…would appear to be…no lasting environmental impact whatsoever”.

How is it possible to really know about lasting environmental impacts at this time? Far too much is not known about a rapidly changing situation. Why not wait to comment on that aspect of this situation (ie, long-term environmental impacts) once more facts come to light in the weeks and months ahead?

Doing so now just weakens the rest of an otherwise strong argument built on facts…that most the nuclear power facilities throughout Japan have held up well to an epic natural disaster, and that even with a series of cascading failures in backup systems, there is still a better-than-average probability that things will turn out ok at Fukushima 1.

And finally, how would acknowledging the lower, but still real, probability of a potentially worse outcome at Fukushima 1 (such as a crack in a containment unit or the like) weaken the point?

There are many valid reasons why a ‘worse-case scenario’ at Fukushima would not invalidate future nuclear power use: the scope of the natural disaster that created the conditions for systems failure; the age of the plant; the location of the plant. The list goes on.

It’s a tough road to plow, and made more difficult by the misinformation and fear surrounding nuclear power. But that makes the clarity of language and delineation between facts and opinions all the more important.

Finally, thank you again to Dr. Brook for this site. Very informative and helpful, even with the concerns I am raising.

TEPCO has a strong financial interest in nuclear energy’s future in Japan. How would downplaying the incident help?

Why do you not remark on the Japanese government’s strong financial interest in natural gas?

“Why do you not remark on the Japanese government’s strong financial interest in natural gas?”

a) I was unaware that it does & b) assuming you are correct, it still doesn’t seem relevant to critcal thinking about questioning statements by TEPCO

@disdaniel: “To wit: are any of you questioning what if things (anything at all) are worse(!) than TEPCO has publicly admitted/stated? Given that TEPCO has a strong financial interest in downplaying the incident…”

I don’t trust neither what the government says nor what TEPCO says (which is the government power company) but we have no other info and the US navy isn’t talking either. If only there were other experts on the ground in nearby towns maybe they could give independent readings to verify what TEPCO says.

I don’t think TEPCO has a financial interest in falsifying data. Actually quite the opposite since they would be in serious trouble if they did.

I did not say they have an interest in falsifying data…I said “downplaying the incident” as you so helpfully quoted. There is an obvious difference

Thanks,Ben,for a calm and reasoned summary of the Japanese situation to date.

There are many lessons to be learnt from this tragedy and I’m not talking about the desirability or not of nuclear power.I say yes to nuclear regardless of earthquakes.

The tsunami appears to have done most of the damage and caused the most loss of life.This holds the lesson that significant structures and facilities which don’t need to be on the coast or on river flood plains should not be built there.

Tsunamis are a relatively rare occurence but rising sea levels are inevitable as are floods of varying frequency.

Worldwide we should be prohibiting new construction in the danger zones and planning a managed retreat from these areas over a hundred years or more starting now.

If we continue to ignore the power of water,fresh or salt,then we get to do all the mourning,recriminations etc ad nauseum on and on all over again ad infinitum.

disdaniel the quote was:

“Zero release of radiation levels OF A DANGER TO HUMAN HEALTH, except for brief periods for those working within the plant compound (NOT PUBLIC EXPOSURE).”

If you have evidence of dangerous public exposure, please provide a link. If you have just ridicule and FUD, you’re not adding much.

FACT.

This was NOT the 4th 9.0+ earthquake “since recorded history”. It is the 6th recorded since 1952. There have been at least 16 events since 1900 8.5 or greater (usgs.gov) , which is well outside the design parameters of Fukushima Two 9.0+ events happened in 1960 & 1964… probably during the Fukushima plant’s planning process!

This earthquake was far from “unthinkable”

I agree with the that nuclear power needs to be part of our future’s energy mix. Nothing is 100% safe, risks must be weighed. Placing nuclear plants near active faults AND exposed to resultant tsunamis is an unnecessary risk.

Downplaying serious risks, skewing facts and defending poor planning is not the way to support nuclear power. I support the use of use of nuclear power in the face of global warming but still find this article aggravating.

If true that is a serious discrepancy in Ben’s article. Perhaps it hinges on the term “recorded history” but I took that term to infer since ancient civilization.

p.s. Or perhaps Ben was referring to the region not the world.

“This was NOT the 4th 9.0 earthquake “since recorded history”. It is the 6th recorded since 1952. There have been at least 16 events since 1900 8.5 or greater (usgs.gov) , which is well outside the design parameters of Fukushima Two 9.0 events happened in 1960 & 1964… probably during the Fukushima plant’s planning process!”

A magnitude 9.0 earthquake how deep under the ground, how far away from the site?

Just looking at the earthquake magnitude figure is not how you determine the seismic design basis – it’s based on the peak ground acceleration.

As somebody mentioned above, the peak ground acceleration experienced at Christchurch was higher than at Fukushima.

Clearly ‘thinking climate’ does not motivate people. Warming of 0.2C per decade, punctuated with extreme weather events, is just not as sexy as a nuclear meltdown. It seems to confirm that we are hard wired to react to perceived short term threats. We make excuses about insidious long term threats. For example I’m astounded that the media hasn’t picked up that crude oil production appears to be in a steady and permanent decline. The lifeblood of the global economic system disappearing before us is evidently not as sexy as low level localised radiation.

This is why the nuclear renaissance is coming like it or not. The same people who demand we abandon nuclear will insist something be done as food, oil and water become scarce. The 24/7 energy needed to overcome this means there is no other palatable alternative.

“A nuclear crisis at the quake-hit Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant deepened Tuesday as fresh explosions occurred at the site and its operator said water in a pool storing spent nuclear fuel rods may be boiling, an ominous sign for the release of high-level radioactive materials from the fuel.”

http://english.kyodonews.jp/news/2011/03/78267.html

-bks

Prior to March 11 there had been four magnitude 9.0 or greater earthquakes since 1900. Now there have been five.

Sorted by magnitude:Largest earthquakes in the world since 1900:

http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/world/10_largest_world.php

Historic earthquakes of magnitude 6.0 or greater sorted by magnitude:

http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/world/historical_mag_big.php

Still attempting to correct the seismology, this earthquake has moment magnitude 9.0 [the Richter scale is no longer in use].

A previous commenter linked to the USGS site. Here is another useful list:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lists_of_earthquakes#Largest_earthquakes_by_magnitude

in which the Sendai earthquake ties for 4th place in the list of earthquakes since 1900 CE.

Radiation decreasing, fuel ponds warming

http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/RS_Possible_damage_at_Fukushima_Daiichi_2_1503111.html

“Approximately 1 hour later, two power plants housing seven nuclear reactors were struck by a 7 metre tsunami. These plants were Fukushima Daiichi and Fukushima Daini.”

Minor correction, there are 6 reactors at Daiichi (Facility One) and 4 at Daini (Facility Two), for a total of ten. 3 of the 6 units at the first facility were already shut down for normal maintenance, before the disaster. Note also that keeping the spent fuel stored at unit #4 (and possibly at #5 and #6) cool and covered is an important issue.

John Newlands has hit the nail on the head. People tend to lock themselves in as either pro- or anti-nuclear and then throw grenades at those across the other side of the fence whilst ignoring the bigger picture facing us all.

In the face of what the world is facing – diabolical climate change and oil depletion – we no longer have the luxury of choosing the perfect way forward. The world has gone past a tipping point and faces a collapse of civilisation as we know it.

That knowledge has spurred many people to look for ways forward and these include nuclear devotees and devotees of various other technologies such as wind and solar and the ‘hot rocks’ people. How sad it is to see them throw grenades at each other rather than pool their efforts.

For my part, I feel frustrated that so many blokes can’t get past supply-side technology solutions – we seem to all work along the lines that if somebody produces and markets monstrous TVs and such then we have a duty to supply the energy to drive them – and have to accept the ever escalating risks of doing so. It’s all glibly passed off as ‘supplying energy needs’.

‘Thinking climate’ means first and foremost knowing when to retreat to safe ground before we just make things worse. Aggressive competition around which technologies best serve us into the long term future may be necessary, I don’t know, but in any event it should be subordinated to that prior purpose.

@ Chris Harries:

The demand for primary electrical generation will be much higher in the future, especially once we can no longer use fossil fuels. We’re going to have to use it for synthesising motor fuel, manufacturing fertiliser, smelting steel, desalinating water and all the rest. If we had another option able to provide us with that as effectively as nuclear can, that would be great, but no such alternative has been demonstrated yet.

John Newlands,I am not sanguine about the inevitability of a nuclear renaissance.

The only inevitability on this Earth is entropy,or death as it is more commonly known.

It is true that the majority of the population think short term only unless strongly encouraged to do otherwise on specific issues.There is a significant section of the population in Australia (not necessarily the best educated or the most powerful) who do think long term. Unfortunately a lot of these people are not thinking in realistic terms in many ways.

The opposition to nuclear power and the virtual blind side to oil depletion are good examples.

BNC is doing stirling work to combat the first instance but to get significant numbers of concerned people marching in the streets etc on this issue is a labour of Hercules.

Painful pressure has to be applied to sensitive parts of the anatomy of the body of power,political and economic,in order to get results.I don’t know of any sure fire way to do this.

“Zero release of radiation levels of a danger to [public] human health”

How sure are we of this at this point? Where was the 400 mS measured?

I also heard of much lower levels in Tokyo. While the levels measured there might not be harmful, it is over 200 miles away. _If_ those levels are from this event, it would seem much higher levels exist in some places – which maybe haven’t been measured yet. Isn’t it going to take a thorough screening of the area in the coming weeks to determine the impact away from the facility?

It seems that people may be jumping to conclusions as to what the final impacts will end up being – on both sides.

Sure, Finrod, you may be correct, but an equal number or people are saying we must supply that energy via other means. I might add that nearly of them are blokes stridently advocating their particular favoured technology, with a lot of panache and verve, and sometimes hostility. There’s an interesting gender pathology in there.

The practicalities of supplying real energy ‘needs’ can’t be ignored, but for every 100 supply-side devotees there appears to be a mere one or two who are talking seriously about the deep cultural shift than must accompany this necessary technology debate.

No set of technological solutions can hope to deliver anything like a complete solution, most of our efforts have to focus on a survivable mode of living in a carbon constrained world.

All this pleading to think “long term” as if it is automatically a superior way to think. I’m certainly not against long term thinking but it isn’t automatically wrong to think short term. In fact right now much of Japan should be thinking short term. Where will these people sleep tonight, how will they be supplied with food and water, how can disease be prevented, what can be done to get people back into meaningful productive employment. In fact I’d argue that much of the time much of the world should be focused on short term priorities.

“This was NOT the 4th 9.0+ earthquake “since recorded history”. It is the 6th recorded since 1952.”

I’m sorry. Please let me correct myself. This was the 5th 9.0+ quake recorded since 1952.

The USGS chart i used has the top 15 earthquakes recorded back to 1900

http://earthquake.usgs.gov/earthquakes/world/10_largest_world.php

I felt it necessary to question Ben’s statement referring to “recorded history” as it seemed unnecessary vague and could give the impression going back of thousands of years.

1. Chile – 1960 9.5

2. Alaska – 1964 9.2

3. Northern Sumatra – 2004 9.1

4. Kamchatka 1952 – 9.0

5. Japan 2011- 9.0

Again I support the use of nuclear power when plants are properly maintained and located out Godzilla’s path .

Hello all,

Author of the post back after the priviledge of a little sleep. Great to see the comments coming, and a few responses are worthwhile.

Firstly, I acknowledge the risk that has been taken in placing any kind of opinion in an unfolding situation. If you consider the post in two parts, the facts of the event impacts may change, but the context will not. Where the facts change I acknowledge this, and certainly the status of radiation levels would benefit from update. Particularly in regard to this point, I acknowledge points well made by @Steve Elbows and @Bob the Builder- the appropriate strategy is a real concern of mine. I think there is a risk though in presuming that nuclear hysteria actually goes away after the event. Past experience would suggest it does not. This partly motivated the decision to post, as well as a sense of some responsibility to the 45 people who listened to me present last week to provide my opinion.

@ Grim, I think your points are also well made, and who would blame the Japanese, a people already uniquely scarred by the mal-effects of radiation, from feeling angry at this additional trauma? Such is the massive challenge of risk communication. As Barry pointed out some days ago, in terms of your chance of dying, you are worse off living near the coast in Japan than near a nuclear power plant. Will this undeniably true statement make anyone feel better? Not a chance. There is much more to the challenge than that.

@Jason, if you would provide a link to that information on quakes I would appreciate it, and would like to read it. I can only ask you to trust me that misleading people is not my business, nor in my interest. I may have confounded my information with that clarified by @ David B Benson, thank you David. Apologies if I did. BUT, what is critical in this context is not the quake alone, so whether or not it was “unthinkable” was not my point. As I discussed, in a risk assessment exercise you would try to construct a horrible scenario to test your system’s capacity to respond. This could relate to nuclear power safety or a parade down main street. A bad event is easy to imagine and plan for. Two massive bad events in close proximity…much harder. Two massive bad events in close proximity, occurring in a part of the world whose pre-existing characteristics (population density, coastal exposure, high penetration of nuclear) seems uniquely well designed to incurr possible high impacts… now we are getting something quite unique, and in a risk assessment setting you would be hard pressed to come up with anything worse. That is the context for understanding the broader implications for nuclear power around the world. As several posts have inferred, yes of course there will and should be changes and lessons for Japan and the rest of world in design and management. But any presumption that Japan turns their back on nuclear really ignores the reality of their energy choices, or lack thereof, something discussed briefly by @lokywoky.

In summary, when I shortly post this to my own site and newsletter, it will be a modified version thanks to the useful comments and discussion that has happened at BNC. What an excellent resource this site is. I would happily re-post the modified version with Barry’s consent, though I am cautious of being overly Orwellian in that manner. I hope the post has been of value, I would judge that is has.

New fire at Unit 4.

http://english.kyodonews.jp/news/2011/03/78383.html?loc=interstitialskip

-bks

While I remain overall a supporter of nuclear energy as a solution to cliamte change, I think this incident highlights an urgent need for change in the industry. I agree the tsunami was a far worse tragedy than the reactor fires, but that does not mean the reactor fres should escape scrutiny. This accident was not lethal, but it was still very serious. Potentially lethal levels of radioactivity were detected outside a reactor. To me, that means failure. The fact that there was not a strong wind blowing towards people at the time was just luck.

I realise that modern reactors are safer than Gen I nuclear reactors, but that does not give Gen I reactors a free pass on safety. If the industry is to remain credible, all remaining Gen I reactors should be phased out of service world wide. This action shows that human intervention cannot be relied upon to solve a crisis. Japan is supposed to have high technical standards. If they can’t prevent this in an emergency, who else won’t? It is not an acceptable public risk in my opinion. For its own sake, I hope the industry realises this quickly.

Ben missed the point. The argument for nuclear is not that it will survive earthquakes and tsunami without deaths and minimal damage etc.

This is opportunism. Any non-nuclear power stations in the same situation would have survived with less damage to workers, less threat to the public, requiring less response, generating far less international concern, and would lead to quicker recovery of capacity.

So in essence Ben’s piece is unthinking, instinctive, spin that demonstrates disregard for the views of the majority of the population and therefore the moral basis of democracy.

There is only one argument for nuclear. It is, on a short-term, balance sheet basis, cheaper than other low-carbon, renewable energy sources.

However there are so many other social, environmental, moral, and economic considerations, particularly driven by exponential growth (waste storage, population, energy demand) that democracy requires alternatives.

The nuclear industry is a modern version of the nicotine industry but with greater complexity than a British Petroleum oil rig.

We all know that the scenario of an earthquake-plus-tsunami was long predicted by the anti-nuclear movement, and if you are not across this – then any pro-nuclear fancy is either political or uninformed.

If high profile anti-nuke activists point to the tsunami that struck a reactor in India in 2004, the fact the Thailand tsunami was 98 feet, and the fact that the San Onofre power station only has Tsunami protect to 30 feet, and earthquake protection up to magnitude 7.0, and all these parameters are exceeded, then the public have every right to be seriously concerned.

If BraveNewClimate was really brave, and really wanted to be a source of information, then I would expect a map of nuclear power stations based on major active fault lines.

While the Newcastle and Christchurch earthquakes did not produce Tsunami, the possibility of a higher magnitude earthquake near Jervis Bay is not zero.

The only solution is to develop various means of baseload renewable energy – ‘blue energy’ (membrane), geothermal, hydro, wave, hydrogen and research better storage systems, liquid metal batteries, pumped hydro etc.

When the Japanese wake up – they will realise that they have now been hit with a huge bill and economic loss on top of the tsunami – purely because the power generators in the path of the tsunami were nuclear. This will not be appreciated.

Support for nuclear is only based on faith. Faith that accidents don’t happen, faith that the next generation will be safe, faith that future developments will solve waste, faith that BP competitive cost-cutting will not jeopardise safety etc.

But the real religion is commercial profits – all the rest is really irrelevant. Even after decades of 100′s of these plants in commercial operation, decent financial information, inclusive of subsidies, is completely unavailable. Most of the costs are foisted onto the public and future generations.

We have to be a wake-up to this sort of nuclear spin:

• Zero deaths from radiation.

[This is distraction – the requirement is zero radiation injuries]

• Zero release of radiation levels of a danger to human health,

[FALSE – some of those working within the plant required hospitalisation]

• Minimal injuries as a result of the hydrogen explosions. [FALSE at least a dozen injured so far]

• No significant or lasting environmental impact whatsoever [except for substantial radiation recorded 100 miles depended on wind direction]

• A major evacuation, which has no doubt been distressing for all involved and with associated costs borne by the public.

• 8 — 10 of Japan’s 55 nuclear reactors known to have varying levels of damage that will impact their ability to provide electricity. The remainder will no doubt require inspection, but would appear to be relatively undamaged until the next earthquake.

So what evacuation area do you need if an earthquake damages a fresh water/salt water membrane plant? How much harm does a release of hydrogen cause? What harm results when a Tsunami washes over a hydro plant. Will a geothermal plant explode if hit by an earthquake?

Scott Elaurant, on 16 March 2011 at 9:12 AM — The reactors in question are considered to be Gen II, I believe.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_reactor_technology#Classification_by_generation

I appreciate the motivations of those behind this blog. Its to address the incredibly serious situation we face with climate change. In that respect I have no problem with their sincerity. I do find their single minded approach that nuclear is the leading means of doing so starting to look a bit like dogma though. Had Japan years ago pursued alternative energy solutions we would now have a major disaster still from the tsunami, but we would not have a situation where people are evacuated in a 20k radius, communications are conflicting and invoking fear in the population and workers are ordered to leave the site where they are most needed due to radiation. Does this blog maintatin that this evacuation is somehow only the result of media hysteria? Is the fact that we are seeing pictures of Japanese safety officials running geiger counters over babies just a reflection of mass hysteria by the Japanese government? If this power plant had been a solar-thermal plant would breakdown problems have presented such a massive logistical evacuation response onto already traumatised people?

I have another question for the editors of this blog. I’m led to understand that no private insurance company anywhere in the world will insure against the possibility of nuclear accident? Is this correct? If so, why do you think this is, given that insurance companies depend absolutely on the most advanced statistical expert methods for evaluating future potential risk, and are happy to insure many other forms of risk such as flood, fire etc etc.

Jim Andrews, how could a solar thermal plant have possibly been built in that area? You do realise that you’d need to cover a vast area, especially at that latitude and meteorological conditions, with enormous storage capability, to generate >4 GWe of baseload electricity, don’t you? Try here for details: http://bravenewclimate.com/2009/12/06/tcase7/

“An estimated 70 percent of the nuclear fuel rods have been damaged at the troubled No. 1 reactor of the Fukushima No.1 nuclear power plant and 33 percent at the No. 2 reactor, Tokyo Electric Power Co. said Wednesday.

The reactors’ cores are believed to have partially melted with their cooling functions lost after Friday’s magnitude 9.0 earthquake rocked Fukushima Prefecture and other areas in northeastern and eastern Japan.”

http://english.kyodonews.jp/news/2011/03/78387.html

-bks

Barry, unlike a nuclear plant, there would not be the same need to build it near the sea. Logically you would build it in the most appropriate area, a mix of solar thermal, wind and other energy options combined with an effort on energy efficiency that has obviously been avoided in Japan due to the belief in endless nuclear power could have sufficed. You’ve missed the point entirely. Any other plant rather than nuclear suffering the same damage would not have resulted in a 20-30km exclusion zone. And you would have to think that had Japan, with all its technological sophistication and wealth, thrown even half the time and money over the last 40 years developing better energy alternatives as well as high-end energy efficiency, we would be in a different place right now.

Further I have a genuine interest in the insurance question. Firstly, am I correct in saying that globally the private sector insurance industry has refused to insure nuclear plants against accident? What is the specific situation in relation to this? If it is they case that they are uninsurable by the private sector, why is this the case given the highly sophisticated risk estimation methods used by that industry?

Jim Andrews there are plenty of private nuclear insurers globally, for example

http://www.amnucins.com/

http://www.nuclear-risk.com/

It is a popular lie on anti-nuclear websites however, so I can understand your error.

Just because many newspapers overemphasize the dangers in this crisis does not mean you should be underemphasizing them.

The situation is still worsening and there is a huge amount of uncertainty.

Jim Andrews, a solar thermal plant would have the same cooling water requirements as a nuclear plant of similar output, so the same considerations that apply to the siting of the nuclear plant would also apply to the solar thermal plant. See the TCASE 6 post for detail on this.

But the point is moot, because Japan is not a viable location for solar power.

Joffan, thanks for that post, I subsequently checked and you are correct in part. Private insurers will insure nuclear reactors, the only problem is that the estimated payouts by the insurers for significant accidents are so high that nowhere are nuclear industry proponents required to pay the full insurance liability. There are several pieces of legislation, such as the Price -Anderson Act in the U.S which cap liability for private operators at a fraction of potential costs then transfer the bulk of liability on to the taxpayer. Unique in relation to energy options. So private insurers will insure against a nuclear accident, its just that the estimated costs of a serious accident is so high private nuclear plants aren’t viable build unless they are covered by taxpayers.

While its a little beside the point its also worth noting that recent solar thermal plant designs reduce water usage by around 90% of current plants. I think the more important point however is not that solar thermal is the answer, but that there is an array of energy options that could have provided the power required generated by that plant. My question would be, if one of these other energy mixes had been used, then affected by a Tsunami, what would the correspondent, precautionary required evacuation zone around it should it be damaged?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/nuclear-reactor-catches-fire-again-as-japan-races-to-contain-radiation-leaks/2011/03/15/ABipVgW_story.html

“Temperatures in the two other offline reactors, units 5 and 6, were slightly elevated, said Edano, the chief cabinet secretary. Fourteen pumps have been brought in to get seawater into the other reactors, and technicians were trying to figure out how to pump water into Unit 4, where the storage pool fire occurred. Early Wednesday, Tokyo Electric Power officials said they had scrapped a plan to use helicopters, deeming them impractical, and said they were considering other options, including using fire engines.”

“Zero deaths from radiation”

Cancer deaths from exposure to radiation often don’t happen for decades. Aren’t you being a bit premature?

A good post, but it seems a bit churlish to ignore the death that has occured and possibly two more, despite the fact it was likely the explosion and not radiation.

http://www.world-nuclear-news.org/RS_Battle_to_stabilise_earthquake_reactors_1203111.html

I question whether this is unique. As far as I know there is no industry that is expected to have insurance for unlimited liability. If a solar power plant had to have unlimited liability insurance then probably no insurance company would insure them. Even though the expected risks from a solar power plant are not unlimited.

p.s. On the insurance issue.

It would seem reasonable that the cost of evacuating people and compensating them for being evacuated ought to be a consideration in insurance. Who will pay for the current evacuation?

If the same resources as used to create nuclear, had been used to develop baseload renewables we would not be in this mess.

Calling reality “hysteria” is not helpful nor relevant.

Any single non-nuclear option is not the answer, we need a mix of:

“blue energy’ (salt/fresh water membranes)

geothermal

wave and tidal

hydrogen fuel cells

hydro

plus improved storage

pumped hydro

liquid metal batteries

augmented by wind and solar.

Ben Heard and others need to stop pushing his agenda, the public do not want nor need nuclear.

Cheap is not nice.

Its not unique. This situation is shared with hydroelectricity, and oil, for instance (witness the taxpayer liability in the recent Gulf of Mexico spill).

In Japan, that array consists of coal, gas and nuclear.

That last comment addressed this remark of Jim’s:

John, there is an array of coal, gas and nuclear becuase the last 40 years has been devoted to those industries unsurprisingly. The point you missed is that had the same effort been diverted into alternatives and aggressive energy efficiency they could have coped without nuclear. I must confess I can’t conceive of the potential risk a solar plant might pose that would equate with a nuclear one. Once again, I appreciate your motivation, I just think your pro-nuclear arguments are perhaps tending to the dogmatic side and there is a concerning strain of seeking to downplay the seriousness of this event. Iteratively revised as new fires etc break out. We all hope its under control as soon as possible, and that no-one is affected. I think its stretching it however to start positing this event as some kind of great vindication of nuclear power as has been mooted on this blog.

“URGENT: Spraying boracic acid eyed to prevent recriticality at No. 4 reactor

TOKYO, March 16, Kyodo

Tokyo Electric Power Co. said Wednesday it is considering spraying boracic acid by helicopter to prevent spent nuclear fuel rods from reaching criticality again, restarting a chain reaction, at the troubled No. 4 reactor of its quake-hit Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

”The possibility of recriticality is not zero,” TEPCO said as it announced the envisaged step against a possible fall in water levels in a pool storing the rods that would leave them exposed. ”

http://english.kyodonews.jp/news/2011/03/78393.html

-bks

@Chris Warren

No one here can speak for the public’s wants or needs. Please take a deep breath.

We are all on the same side here. We are all deeply concerned about climate change.

This is not a black and white issue.

Jason, on 16 March 2011 at 11:32 AM said:

Missed the point. Reporting what the public wants is not “speaking for the public”.

Policy makers always need to be mindful of exactly what the public wants and needs including future generations.

You need to broaden your perspective and take a moral compass to these issues.

Climate change is not moot – as the choice between baseload renewables and nuclear is not germaine – both have fossil fuel replacement effects.

You have confused issues and missed the point.

The development of nuclear industry is entirely subject to what the public needs and wants.

There is no alternative in a modern democratic state.

@Jim Andrews

Well said.

Downplaying the current situation has created unnecessary debate AND division here, even with those inclined to agree with the need for nuclear power.

“White smoke billowing from Daiichi plant.”

Seen from helicopter 30 km away, live on

NHK/TV.

Not sure of translator’s accuracy so grain of salt.

-bks

“Each phase of the catastrophe is perhaps the most powerful of its kind that we will see in our lifetimes.”

So long as you were born later than 2004. The Sumatra-Andaman earthquake was 9.1-9.2 on the richter scale, with a tsunami as high as 30m in some locations.

Steve, on 16 March 2011 at 12:01 PM — Nobody uses the Richter scale anymore. It is the moment magnitude scale, usually abbreviated to just ‘magnitude’.

I haven’t got a barrow to push in relation to any energy source but it is worth considering how many hydro-electric facilities in the world could potentially be affected by a major seismic event, and the potential human calamity that could eventuate from a burst dam.

Here is a sobering example: Only 2 years ago an accident at a Russian hydro-electric facility killed 76 workers instantly. (That was not a seismic event just a mechanical accident.) See here for a summary: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/worldnews/article-1207093/Accident-Russias-biggest-hydroelectric-plant-leaves-seven-workers-dead.html

In addressing climate change we can’t ignore hydro-electricity, nor nuclear, nor solar, nor wind – in spite of their various potential dangers or energy supply limitations. We simply don’t have a silver bullet.

But these dangers and limitations do tell us one thing loud and clearly, our primary response should be to limit energy demand as Number 1 priority.

On insurance. There is a lot of smoke and mirrors here with regards to insurance. All US reactors are insured up 12 billion or so…because they are self insured.

Secondly, what is ‘liability’ anyway? Seriously? In the US the idea of the ‘limitation’ is that the gov’t will pick up the costs of damages in a ‘worst case scenerio’. WTF is that? It’s a *political* designation based on that old Sandia National Labs report from the 1950s about wiping out half the state of Penn. in the US. So by LAW, insurance has to cover THAT worse case scenario.

In the litigious U.S., this means ‘damages’ which can be as ephemeral as headaches to as terrible as family members dying from cancer to almost anything. Thus a ‘cap’.

In my opinion, if you are in fact hurt, or killed, people have a right to sue, corps. should be responsible, no liability.

At any rate Price Anderson has never paid a dime out, even after TMI.

David

There are now news reports of radioactive clouds spreading across the region. The Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre is warning airlines not to fly into the area and there are claims that a primary containment structure has been breached. It would seem that Ben’s claim of no radiation damaging to human health being released was premature.

This may have already been posted:

“The workers cannot carry out even minimal work at the plant now,” Edano said. “Because of the radiation risk we are on standby,” he said

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/Japan-suspends-work-at-apf-3314845701.html?x=0

In terms of climate change, the need for Nuclear Power on the Australian mainland is well and truly overstated. Australia is in a unique position in the world to harness and enhance the collection of energy through natural, renewable resources. Our funding is better invested in these ventures.

On climate change – everyone says that we need to be careful of what we do to the planet, as a legacy to future generations.

Some byproducts of nuclear fission in High Level Waste has half-lives of millions of years. Is this the legacy we want to leave? “Here kids, here is some extremely dangerous and toxic waste. We need to be minding it to make sure it doesn’t get out for generations. Enjoy”.

I simply do not see this as an acceptable compromise. Not yet anyway. Until we can come up with a safe way of neutralising radiation, we should not consider it an option when we have others without such byproducts.

Nice article…However you have very conveniently OMITTED some of the most important FACTS….

(1) Integrity of container at 2 is known to be compromised. (announced by authorities)

This means that, at the very least, very bad stuff is being absorbed by the soil and it will be thrown up in the atmosphere in case of any further explosions

How can you possibly state ” No significant or lasting environmental impact whatsoever” …come on…

(2) Reactor number 4 has a highly dangerous situation with spent fuel rods. These have been exploding and burning.

Ah…and yes…There were spent rods on top of every reactor, the roofs of nearly all of them have blown…where did those spent rods go?

Monica

If you read today’s update you will see that the container of reactor 2 has not been compromised. The suppression pool under it has a crack in it. Nothing has been thrown up into the atmosphere from the nuclear containment vessel. Other radioactive gases in the steam emitted have a very short half life and dissipate locally in seconds hence the sudden spikes and drops in the readings.As to your comment reproduced below:

“2) Reactor number 4 has a highly dangerous situation with spent fuel rods. These have been exploding and burning.

Ah…and yes…There were spent rods on top of every reactor, the roofs of nearly all of them have blown…where did those spent rods go?”

Please give your sources for this information as far as I know this has not happened. Spent fuel rods are inside the building not on top of it literally ,so blowing the roof and some of the walls would not have ejected any spents rods. I really think you should go back and read the information about the current state of the reactors. Things like the spent fuel rods are explained in terms easily understood by the layperson. And put your mind at rest -present radiation levels are not any danger to human health. There are plenty of links for you to check this out on BNC.

@Chris Warren wrote:

“So what evacuation area do you need if an earthquake damages a fresh water/salt water membrane plant?”

Chris, have you ever looked at the US DOT Emergency response guide? http://www.phmsa.dot.gov/staticfiles/PHMSA/DownloadableFiles/Files/erg2008_eng.pdf

There are evacuation and protection distances in there on the order of 11+ km for spills involving as little as a single rail tankcar of certain substances. (See oxygen difluoride as a particularly nasty example). No one is up in arms that whole _trains_ of these chemicals routinely pass through our towns and cities.

It seems that man’s irrational fear of things that cannot be seen has taken control of the mass [hysteria] media. If you recall on day 1 of the disaster there were videos of a giant refinery burning, send massive plumes of black smoke into the air – there was no “OMG we’re all gonna die!” coverage for that. In fact, that footage was used as an interstitial when cutting to a commercial!

In my opinion that single refinery fire will contribute to more deaths and premature illness than all of the reactor releases.

How many other refineries/chemical plants/heavy industry sites released massive amounts of toxic substances into Japan’s environment, particularly it’s water table?

In this case, familiarity does not breed contempt, but complacency. No one bats an eye when there are releases of things they can see, touch, or understand. People mishandle dangerous things like gasoline all the time, even going as far as to siphon it by mouth. How many of them would swish around a sip from a beaker of ‘mixed aliphatic hydrocarbons’?

Congratulations Barry on such an informative site that is so full of up to date factual information on climate change, nuclear energy and lately the Japanese nuclear crisis. No wonder 800,000 people from all over the world have logged on over the last few days almost doubling your stats counts.

I also thank Ben Heard for his excellent post and his welcome dose of reality. The end game is mitigating global warming caused by GHG emissions from the burning of fossil carbon fuels such as coal, gas and oil to produce the vast quantities of energy needed to sustain our modern world.