Over the next month or two, I will publish four extracts from the book Plentiful Energy — The story of the Integral Fast Reactor by Chuck Till and Yoon Chang.

Over the next month or two, I will publish four extracts from the book Plentiful Energy — The story of the Integral Fast Reactor by Chuck Till and Yoon Chang.

Reproduced with permission of the authors, these sections describe and justify some of the key design choices that went into the making the IFR a different — and highly successful — approach to fast neutron reactor technology and its associated fuel recycling.

These excerpts not only provide a fascinating insight into a truly sustainable form nuclear power; they also provide excellent reference material for refuting many of the spurious claims on the internet about IFR by people who don’t understand (or choose to wilfully misrepresent) this critically important technology.

The first extract, on Fuel Choice, comes from pages 104-108 of Plentiful Energy. To buy the book ($18 US) and get the full story, go to Amazon or CreateSpace.

—————-

Metal Fuel

The IFR metal alloy fuel was the single most important development decision. More flows from this than from any other of the choices. It was a controversial choice, as metal fuel had been discarded worldwide in the early sixties and forgotten. Long irradiation times in the reactor are essential, particularly if reprocessing of the fuel is expensive, yet the metal fuel of the 1960s would not withstand any more than moderate irradiation. Ceramic fuel, on the other hand, would. Oxide, a ceramic fuel developed for commercial water-cooled reactors, had been adopted for breeder reactors in every breeder program in the world. It is fully developed and it remains today the de facto reference fuel type for fast reactors elsewhere in the world. It is known. Its advantages and disadvantages in a sodium-cooled fast reactor are well established. Why then was metallic fuel the choice for the IFR?

In reactor operation, reactor safety, fuel recycling, and waste product—indeed, in every important element of a complete fast reactor system—it seemed to us that metallic fuel allowed tangible improvement. Such improvements would lead to cost reduction and to improved economics. Apprehension that the fast reactor and its associated fuel cycle would not be economic had always clouded fast reactor development. Sharp improvements in the economics might be possible if a metal fuel could be made to behave under the temperature and radiation conditions in a fast reactor. Not just any metal fuel, but one that contained the amounts of plutonium needed for reactor operation on recycled fuel. Discoveries at Argonne suggested it might be possible.

Metal fuel allows the highest breeding of any possible fuel. High breeding means fuel supplies can be expanded easily, maintained at a constant level, or decreased at will. Metal fuel and liquid sodium, the coolant, also a metal, do not react at all. Breaches or holes in the fuel cladding, important in oxide, don’t matter greatly with metal fuel; operation can in fact continue with impunity. The mechanisms for fuel cladding failure were now understood too, and very long irradiations had become possible. Heat transfers easily too. Very little heat is stored in the fuel. (Stored heat exacerbates accidents.) Metal couldn’t be easier to fabricate: it’s simple to cast and it’s cheap. The care that must be taken and the many steps needed in oxide fuel fabrication are replaced by a very few simple steps, all amenable to robotic equipment. And spent metal fuel can be processed with much cheaper techniques. Finally, the product fuel remains highly radioactive, a poor choice for weapons in any case, and dangerous to handle except remotely.

Important questions remained—whether uranium alloys that included plutonium could be developed that had a high enough melting point and didn’t harm the fuel cladding, while at the same time retaining the long irradiations now possible for the uranium EBR-II fuel. Early metal fuel had swelled when irradiated—the reason it had been discarded. But the swelling problem had been solved for all-uranium fuel. EBR-II had been operating with fairly long burnup uranium metal fuel for over a decade. Long-lived metal fuel resulted from metal slugs sized smaller in diameter than the cladding that allowed the metal to swell within the cladding. If properly sized, the metal swelled out to the cladding in the first few months of irradiation, and when it did, it exerted very little stress on it. After that, the fuel would continue to operate without any obvious burnup limit nor any further swelling.

Before the metal swelled sufficiently to give a good thermal bond with the cladding the necessary thermal bond was provided by introducing liquid sodium inside the cladding. The compatibility of liquid sodium with uranium metal allows this. As the fuel swells, sodium is displaced into the empty space at the top of the fuel pin, provided to collect fission product gasses. The bond sodium is important. It provides the high conductivity necessary to limit the temperature rise at the fuel surface and therefore the temperature of the fuel itself. The swelling itself, it was found, is caused by the growing pressure of gaseous fission products accumulating in pores which grow in size in the fuel as operation continues. But as swelling goes on, the pores interconnect and release the gasses to the space above. At less than 2 percent burnup the point of maximum swelling is reached, and the interconnections become large enough that sodium enters the pores. This, in turn, has the effect of restoring heat conductivity, which then acts to minimize the fuel temperature rise in the fuel.

The Fuel Conditioning Facility at EBR-II, the prototype of the IFR. Near the centre of the picture (with checkered cardigan) is Dr. Charles Till, who directed the IFR programme from 1984-1994 and is one of the authors of "Plentiful Energy".

The soundness of the basic uranium design had been established by thousands of uranium fuel pins of this design that had been irradiated without failure in EBR-II. But now, metallic uranium-plutonium would need to be designed to accommodate swelling. Would the plutonium content cause swelling behavior different from uranium alloy? And, more worrying, plutonium forms a low-melting-point eutectic (mixture) with iron, below the temperature required for operation. A new alloying element would be necessary to raise the eutectic melting point. Zirconium was known to be helpful in that. Zirconium also suppressed the diffusion of the cladding elements, iron and nickel, into the fuel. Iron and nickel form a lower melting point fuel alloy; worse, they form those alloys in the fuel next to the cladding. Zirconium solves these problems. Ten percent zirconium was chosen as optimal, because higher amounts gave fuel melting points too high for the techniques we intended to use to fabricate the fuel. Ten percent gave fuel with adequate compatibility with the cladding, and a high enough melting point to satisfy operating requirements, and could be fabricated with simple injection-casting techniques.

Thus the fuel would be a U-Pu-10Zr alloy. But would it work? Ten percent burnup, about three years in the reactor, was our criterion for success. We would have one set of tests initially, and everything depended on its success. In the event, the fuel passed 10% with no difficulty. It got close to 20% before it was finally removed from the reactor. There were no failures (such as burst cladding). The very first IFR fuel assemblies ever built exceeded the burnup then possible for oxide fuel in the large programs on oxide development of the previous two decades. Metal fuel which included plutonium had passed the test. All the benefits from its use were indeed possible. The program could then turn to a thorough sequence of experiments and analysis to establish, in detail, its possibilities and limitations.

Plutonium

The IFR fuel cycle is the uranium-plutonium cycle. In this, non-fissile uranium-238 is converted slowly and inexorably to fissile plutonium-239 over the life of the fuel. If there is a net gain in usable fuel material, the reactor is a breeder; if not, the reactor is a called a converter (of uranium to plutonium), as are all present commercial reactors. But all reactors convert their uranium fuel to plutonium to some degree. Water reactors convert enough that about half the power the fuel eventually produces comes from the plutonium they have produced and burned in place. A significant amount of the plutonium so created also stays in the spent fuel.

A large and lasting nuclear-powered economy depends on the use of plutonium as the main fuel. The truth about this valuable material is that it is a vitally important asset. Its highly controversial reputation has been built up purposefully from the activists, with little countervailing public awareness of its “whats and whys.” Its very existence is said to be unacceptable. In this way, breeder reactor development was stopped in the U.S. and today continues only fitfully around the world. The fact that present reactors fueled with uranium convert uranium to plutonium very efficiently indeed, creating new plutonium in yearly amounts comparable to the best breeders possible, is lost in the rhetoric. But facts are facts. The principal plutonium-related difference between breeders and converters is that breeders recycle their plutonium fuel, using it up, cycle after cycle, so the amount need not grow. Present reactors leave most of the plutonium they create behind as waste. For efficiency in uranium usage, there is little incentive to recycle it; perhaps a twenty percent increase in uranium utilization is achievable, at a considerable cost to the fuel cycle. (Other reasons, such as waste disposal, may make reprocessing of thermal reactor fuel attractive, but not the cost benefits of plutonium recycling.)

However, it is plutonium that brings the potential for unlimited amounts of electrical power. Plutonium no longer exists in nature except in trace amounts. Its half-life is too short: 24,900 years. The earth’s original endowment decayed away in the far distant past. It has to be created from uranium in the way we just described. Plutonium is a metal. It’s heavy, like uranium or lead. It is chemically toxic, as are all heavy metals if sufficient quantities are ingested, but no more so than the arsenic, say, common in use for many years. It is naturally radioactive, but no more so than radium, an element widely distributed over the earth’s surface. Its principal isotope, Pu-239, emits low-energy radiation easily blocked by a few thousands of an inch of steel, for example, and it is routinely handled in the laboratory jacketed in this way. It is chemically active, so in fine particles it reacts quickly with the oxygen in the air to form plutonium oxide, a very stable ceramic. If this is ingested, either through the lungs or the digestive system, as a rule the ceramic passes on through and the body rids itself of it. A popular slogan by the anti- nuclear organizers is that “a little speck will kill you.” Nonsense—a little speck of the ceramic plutonium oxide will not react further, and will generally pass through the body with little harm.

Plutonium has been routinely handled, in small quantities and large, in laboratories, chemical refineries, and manufacturing facilities around the world for decades. There have been no deaths recorded from its handling in all this time. A study of the wartime Hanford plutonium workers gave the unexpected result that these people on average lived longer than their non-plutonium-exposed cohort group. This was explainable as the likely result of better and more frequent checkups because they were involved in the study, but at the very least there was certainly no shortening of lifespan.

The last point is plutonium’s use for weapons. The very fact that Pu-239 is fissile makes this a possibility, as it does also for the two fissionable isotopes of uranium, U-233 and U-235. But plutonium for a time was exceptional because it could be chemically separated from the uranium that it was bred from, and it did not require the large, expensive diffusion plants necessary for the separation of the fissile U-235 isotope of uranium. But this ease of acquisition argument changed with the development of centrifuges. Now the fissile element U-235 can be separated from bulk uranium with machines. And instead of a stock of irradiated fuel, a chemical process, and facilities for handling, machining, and assembling a delicate implosion device, as one must have for plutonium, for uranium one has a nearly non-radioactive natural uranium feed, centrifuges that can be duplicated to give the number needed, and a nearly non-radioactive product, easily machined and handled, which allows a more simply constructed weapon. Plutonium can no longer be singled out as more susceptible to proliferation of nuclear weapons than uranium. The fact is that uranium now is probably the preferred route to a simple weapon in many of the most worrying national circumstances. Iran’s current actions are a case in point.

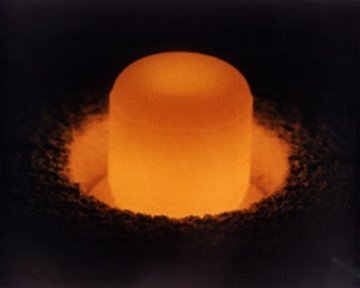

Plutonium-238 (plutonium oxide). Nuclear fission reactions release enough energy to increase the temperature of this sample of plutonium to red-heat. The heat produced by plutonium has been used as an energy source on spacecraft. Photo: Department of Energy.

Weapon-making is complicated by the presence of radioactivity. Plutonium processed by an IFR-type process remains very radioactive; it must be handled remotely, and delicate fabrication procedures are correspondingly difficult. Uranium is so much easier. This is not to imply that the large and sophisticated weapons laboratories like Los Alamos or Livermore could not use such isotopically impure reactor-grade plutonium; it is sufficient to say they would not choose to do so with much more malleable material available. And the beginner would certainly avoid the remote techniques mandatory for IFR plutonium.

This is the situation: Plutonium, as used in the IFR, cannot be simply demonized and forgotten. It is the means to unlimited electricity. The magnitude of the needs and estimates of the sources that might be able to fill those needs lead to one simple point: Fast reactors only, taking advantage of the breeding properties of plutonium in a fast spectrum, much improved over any uranium isotope, can change in a fundamental way the outlook for energy on the necessary massive scale. Their resource extension properties multiply the amount of usable fuel by a factor of a hundred or so, fully two orders of magnitude. Fine calculations are unnecessary. Demand can be met for many centuries, by a technology that is known today, and whose properties are largely established.

This technology is not speculative, as are fusion, new breakthroughs in solar, or other suggested alternatives. It can be counted on.

.png)

I’m also part-way through my first reading of the book, nearly finished in fact.

Mr. Holland, If you want technical details about pyroprocessing and the IFR design only I suggest you skip the first couple of chapters, as they’re mainly history (and therefore political) chapters. I did find those chapters helpful for getting a grip on the history of the technology though, but each to his own.

I’ve found that Till and Chang tend to repeat what they’re saying about the basic IFR characteristics quite a bit in the chapter introductions, which gets a bit tedious.

I would concur that they don’t mention many downsides that are inherent to the reactor technology.

I would also add that they say nothing (or I have missed in my first pass of reading so far) about the power characteristics such as theoretical electrical power ramp-up/ramp-down rates in comparison to existing reactors. Are we therefore safe to assume that as they use steam turbines similar to PWRs (minus the large sodium-water heat exchangers) that they would have similar ramp-up/ramp-down rates? Or are there IFR-specific features perhaps such as faster reactivity controls that would lead to better control of power output?

Mr Holland, please repost you short critique (if you wish) in the book’s main comment thread, here: http://bravenewclimate.com/2012/01/05/plentiful-energy-ifr-book/

General Guideline: Please use that thread for general comments about the book, and reserve this one for specific comments about fuel choice in the IFR. Otherwise it will get confusing/off track.

Will, this post (albeit mostly focused on the French oxide experience) may answer some of your queries about reactivity control in fast reactors: IFR FaD 6 – fast reactors are easy to control

Does this design reduce the following risks of nuclear power plants, you still require pump power to cool do you not.

The biggest risk now with nuclear power is almost anyone can cause a meltdown. WE know from TMI that a switch out of position can cause a meltdown; it is easy for a person with basic electronics to get hired on at a plant and screw with switches and relays. A person spending about $5,000.00 could wire in wireless remote controls to change readings at will. Also I have read about sun surge in 1860′s that was so massive that the electrical surge was so high that it will take out all electrical power including battery, generators and main power grid. This was many times greater than the surge that hit the Quebec power grid several years ago that toke it out. This could mean that all the plants in the world facing the sun when the surge hits will go into a meltdown all at the same time could be over 50 plants involved. These plants are vulnerable to cosmic events including comet showers. But this does not stop the industry I do not know what will other then demanding the leaders of each country shut them down no courts involved.

(Comment deleted – off topic.)

MODERATOR

Please re-post this critique of the book in the “Plentiful; Energy” thread. Once done I will delete this comment.This thread is for comment on the IFR Fad 10. Time limit for re-post has expired.

One question that came up for me as I started to understand the importance of the choice of metal for the fuel is, what about GE’s PRISM? Can anyone point me to material I can study that will clarify what the difference is between GE’s PRISM and the IFR?

Would commenters please note Barry’s directions that any critiques on the book should be posted in the “Plentiful Energy” thread.

Please reserve this IFR Fad 10 thread for comments relating to that subject only.

Failure to do so will result in a messy and confusing thread.

David Lewis, there’s no real difference. The GEH S-SPRISM is a 311 MWe commercial implementation of the IFR, although the initial proposal in the UK is not immediately integral because the fuel recycling would not be on-site. To quote a recent post from Dan Yurman:

Richard Perry, the IFR has passive cooling of its fuel. If there is a total loss of external power, like what happened at Fukushima, the reactor can self-cool indefinitely with an external heat exchanger. There is no need for an active core-cooling system like in water-moderated reactors, and the type of meltdown that has occurred at TMI and Fukushima (due to loss of cooling, conversion of RPV water to steam etc.) does not occur. Indeed, part of the PRISM design is to cool the recently used fuel (pre-recycling) within the reactor sodium pool, rather than in cooling ponds.

One point on plutonium covered elsewhere in the book concerns how breeders and plutonium got their present “bad” reputation.

“The methods of reprocessing commercial nuclear fuel in current use in several nations (but not in the US) were actually developed originally to provide very pure plutonium for use in nuclear weapons. The commercial plants have that same capability….”. It is this point the antis have exploited to the point people who should know better repeat mindlessly that if civilization turned to breeders in order to phase out fossil fuels quick there will be weapons grade plutonium transported around all over the place as a result.

I.e. Dr. Kevin Anderson, former Director of the Tyndall Centre in the UK explained exactly that, i.e. breeders can’t save us, because the threat from the huge quantities of “weapons grade” plutonium that will inevitably be produced is too great, recently. His line is civilization, because of the size of the present fossil infrastructure and the unprecedented and therefore plausibly impossible rates of emission phaseout that would be required to keep warming below 2 degrees, faces an “impossible” future, i.e. warming of such extent it will prove to be “incompatible with an organized global community”. Etc. voice of doom. But he is not acquainted with the IFR design.

The book explains the pyroprocessing in great detail. What Till and Chang want people to understand is this: “the process cannot purify plutonium from the IFR spent fuel; it is scientifically impossible for it to do so. (page 42). The IFR technology should not contribute to weapons proliferation. On the contrary, by replacing present methods it should substantially reduce such risks”.

This link http://www.lakestay.co.uk/pluto.htm says the UK has 108 tonnes of plutonium. My reading is that is mostly as already separated oxide (via PUREX type processes) and mostly held at Sellafield. It also explains why the MOX option is not preferred.

Reduction to metal must be a costly and difficult extra step. I wonder how many people inhale lead compounds which have that distinct odour when you clean the positive terminal on a car battery.

John, PE describes a pyroprocess (electroylsis in molten salt) for reduction of spent oxide fuel to metal. The oxide forms the cathode, and a voltage applied through molten LiCl / 1% Li2O at 650 C to deposit the metal on a Pt anode. Nothing’s simple, but it doesn’t appear more complex than the pyroprocessing loop for the main IFR fuel cycle.

DL, quite right. Indeed the only way to get weapons-grade Pu out of a pyroprocess is to put weapons-grade Pu in. I wish more people would understand this, especially the Kevin Andersons of this world, who advocate for substantive decarbonsiation but have not taken the (relatively small amount of) time to familiarise themselves with the crucial technology solutions that they try and critique. Very frustrating.

JN, I doubt that reduction from LWR oxide fuel to metal will be particularly expensive, but this step needs to be proven at a commercial scale (which is what the UK implementation would do). There is a whole chapter in Plentiful Energy on the LWR oxide -> metal fuel process.

I had seen documents, such as this one, where GE envisions at least some installations where fuel “recycling” (they prefer this word to reprocessing) will be on site.

On the other hand, GE offers documents like this which leave out any mention of the fuel recycling feature.

So metal was rejected by the Rickovers of this world who thought they knew all about how to commercialize new designs. But some at Argonne couldn’t forget about metal’s advantages.

Because they kept on experimenting with metal reactors by running one they overcame the problem. The result was the sodium filled rod that allowed the metal fuel pins to expand somewhat before hitting the cladding design. By solving metal’s great problem they discovered a great advantage. The onsite reprocessing they were forced to resort to in order to make their metal reactor experiment economical, when it became “good enough”, turned this bug into a feature.

So now they’ve got a system where all plutonium produced is recycled out of the waste stream and sent back into the reactor because they’ve got onsite el cheapo recycling facilities. The way Till and Chang write about the evolution of the design it almost sounds like the famous “Puffed Grass” commercial where, we’re told, “science works for YOU here at Eating Corporation of America”, when the gardener dumped the lawn clippings into the Puffed Wheat machine by mistake and created the first Puffed Grass.

However they came up with it, it is a breakthrough advance. They do caution in the book that the process needs further development. It was disappointing to read that. Blees had sort of convinced me the IFR was a design that was ready to deploy at full scale right now. I’d be interested in more detail on what a civilization that was on a war time footing now that it had realized how badly it had blown its climate problem could do.

I think the fuel fabrication could be done more economically. The uranium could be converted to metal, which has a reasonably high melting point of 1132C. Reduction of PuO2 to a metal with a melting point of 639C could be avoided. Uranium could hold the ceramic PuO2 in a Ceramic-Metal form. With nearly three-fourth of lighter oxygen nuclei gone, the breeding ratio advantage will be proportionally obtained.

If we use in cermet fuel higher melting and better heat conducting thorium metal, we sacrifice the fast fission of U238 but go on to create better fissile U233. Thorium could be used with ceramic PuO2 or with metallic U233. Metallurgical problems of metallic Pu are better avoided.

How about what happened at Monju Nuclear Power Plant in Japan a few years back. This looks bad as there are few of these type of reactors and have problems. The problem was caused from a break in the piping for the cooling system. It is bad when all it takes is a pipe to break and the plant goes into critical mode.

Interesting that the metal fuel solution was to just give the fuel a volume in which to expand. Very simple….and undoubtedly thought up by someone with a mechanical engineering background 🙂

Loved the book. Too bad homo sapiens is too backward and stuck in their ways to implement the IFR.

Perhaps by 2100 or so the human race will wake up and realize there is not much choice.

I’ve just ordered the book!

Can someone please flesh out one detail for me. The “remote handling” point about IFR plutonium. If you had a work force

willing to die, could you handle plutonium other than remotely. How quickly will it sicken or kill? I’m not actually sure that such a work force is possible … suicide bombers are not the same thing as suicide engineers … but I’d still like the detail.

Geoff, GRL Cowan constructed an estimate of suicide engineer survival time for spent IFR fuel in this comment 3 years ago:

Thanks John and thanks GRLC … that’s exactly the kind of detail

that is needed when talking about this stuff to people.

I think, to put it in plain language, there is simply no way to remove this material from the reactor site without an engineered system in place to do it, with all the forethought, design, planning, construction, testing and capital expenditure that implies.

It is not the sort of thing that could be achieved by either surreptitious material subversion, or a raid, no matter how well manned and armed, to address two popular fantasies.

“The biggest risk now with nuclear power is almost anyone can cause a meltdown…” comment is recycled verbatim from elsewhere.

Here’s an example of what “Richard Perry” brings to a conversation about nuclear energy (starting at comment #59): http://depletedcranium.com/the-other-fukushima-nuclear-power-plant/?cp=all#comments

Interesting comments thread on Depleted Cranium, thanks Seamus. Richard Perry, trolling is not allowed on BNC, and you are skirting perilously close to that by the tone/nature of your comments. Be on notice.

Monju had a sodium leak in its secondary piping, which was quickly cleaned up, but also covered up, and when someone found out about the cover up, it created all of the legal/bureau/admin problems. It didn’t send the plant into ‘critical mode’, and to say this indicates that you have no idea what you are talking about on this issue.

Putting that aside, the IFR is not a Monju-type reactor anyway. The IFR uses metal fuel instead of oxide, it has a pool design instead of loop, it uses double-walled piping instead of single-walled like Monju (so a leak in an IFR internal pipe can be detected and repaired without any sodium leaking), etc. As a result of these innovations, the EBR-II ran perfectly for many decades, without leaks.

Barry Brook, with the amount of money put into this plant and time not running I would call that critical. I have read now they have shut it down. Barry, I am very glad to hear that there are safe guards put in place since this plant, this is good to see. Zirconium be careful at different temperatures and repeated changes in temperature. Looks good but I believe with all the new standards the cost will be in the way. Sorry if I came across as aggressive, but I believe nuclear is the way to go but only if it is safe but the owners want it built and run cheap to compete in the market is a problem.

Richard, the IFR design doesn’t use zirconium in its cladding like in water-moderated reactors – it uses stainless steel. There is also no water present in the reactor vessel, so no Zr-catalysed hydrogen can be evolved.

Zr is alloyed in the metal fuel pins, to control the melting point (U-Zr was used in EBR-II, the final IFR fuel is envisaged as U-Pu-Zr10 alloy). I’d encourage you to read the Plentiful Energy book to find out more.

I may have missed a point in my reading of PE. The book explains that the alloy of U-Pu-10Zr is soft enough to allow the gaseous fission products to form pockets, so that the fuel foams and expands to fit the the width of the stainless steel canister. With enough gas in the pockets and the plenum at the top of the canister, any expansion of the fuel will be taken up without splitting the container. Well, almost any.

Elsewhere (on BNC if not in the book itself) I have gathered that in the event of a nuclear excursion, the fuel would expand so that its increased surface area would bleed excess neutrons and limit the excursion. I can imagine the entire core expanding over a few minutes into a giant popcorn. But that is an end-of-reactor event rather than occasional control mechanism. Is there a gentler self-limiting response that doesn’t require the fuel to break out of the canisters?

Roger Clifton, I think whats going on here is that gaseous fission product builds up slowly, so the fuel expands over a period of presumably months, before dimensions stabilize when the pore structure percolates. Reactivity changes are compensated by control rod operation to keep the criticality factor k~1.

But the fuel density will respond immediately to a change in temperature, so any power excursion immediately has a negative feedback on reactivity (time constant of a few ms). The difference between prompt and delayed criticality is less than 1% of the neutrons (for a LWR at least), so it doesn’t take much neutron loss to turn the wick down. In one of the EBRII pull-the-plug experiments the temperature shot up a couple of hundred degrees in not many seconds before negative feedback kicked in. Metal density will change a fair bit in that range. I also think there is a negative feedback from high temperature increasing the relative speed of neutrons to nuclei, so the cross section is reduced.

In other words, I don’t think its an irreversible popcorn event, rather a reversible expansion/contraction.

Roger, the scenario you describe is not damaging to the IFR and would not result in burst cladding. We know this, because during the two 1986 ATWS safety tests (LOF and LOHS), the EBR-II remained completely undamaged during the induced power excursion. The fuel pins expanded, criticality was reduced, and the reactor shut down to low power levels and self cooled thereafter. This is all described in the PE book.

Indeed, one test was run in the morning, then the reactor was powered up, and the second test was run in the afternoon. The expansion required to reduce criticality is far below that which might cause irreversible fuel warping. No popcorn event, we know that for sure.

Here is why we need it. It is probably already too late, even 1994 may have been just in time. None the less, its cancellation is a story well worth telling, since we literally chose the end of the world.

This is the only thing we have to tackle the limits to growth.

http://www.collapsenet.com/free-resources/collapsenet-public-access/item/6569-the-ultimate-zombie-litmus-test

Problems of sodium coolant have been brought up in many posts. There are two lines to a solution of the fire risk, but a related issue is compatibility of coolant with containers and piping.The two lines are:-

1. Salt coolant. A combination of NaF, PbF2, SnF2 and ZrF4 in various combinations will meet the requirement. More is given in document

http://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/files/Pub29596.pdf

2. (a) Metal coolants tried out by Russians like Lead or Lead-Bismuth. It is more damaging to metals than sodium.

(b) A Al-Mg eutectic expected to be benign to metals. It burns at a higher temperature bringing in a higher margin of safety.

The next PE extract post will be specifically on the coolant choice (sodium and other options), so we can talk about that more then.

Another choice of fuel in a fast reactor but generally discussed as a different class of reactors, is liquid fuel. Chlorides of uranium and Plutonium have low melting points and can easily be used as liquid. One advantage of liquid fuel is that fission gases, Xe and Kr can be constantly removed.This would, however require isotopic separation of chlorine and Cl37 used.

Another advantage of liquid chloride fuel is the ease of processing to partition the irradiated fuel into fission products, uranium and Transuranics.

(Deleted off topic. Please re-post in the OT)

(The comment to which you refer has been deleted as off topic.)

(The comment to which you refer has been deleted as off topic)

(Deleted as off topic. Please re-post in the OT)

(The comment to which you refer has been deleted as off topic.)

Please do not post off topic comments. The Open Thread is for this purpose. BNC does not have the facility to move posts for commenters so please keep a record of your comments to enable you to easily re-post elsewhere, when directed.

Off topic comments tend to distract, confuse and lead the thread off-track. When I am not on the blog these comments build up and cause people replying to them to be mis-led as to the proper place to respond. Thankyou.

I agree with the metal fuel and metal bond philosophy outlined here.

Apparently the biggest scale-up/commercialization issue is the fuel processor. So why not just build the reactor on low enriched uranium metal fuel? Operate in once-through mode and a bit higher burnup. Reserve some space for a future processor unit. Get started right now with the reactor. When the processor is available, add it on and start processing spent fuel, and switch to a bit lower burnup mode.

@Cyril,

Isn’t this what GE are proposing for the UK reactor, except for using depleted U + plutonium out of the UK stockpile rather than paying for enrichment? There is no plan to build the fuel processing plant at the moment, but nothing to stop it being done later if policy changes. They get to demonstrate the reactor, and establish real world costs and schedule for FOAK plant. It will not be economic on fuel costs because there will be far too much fissile left in the discharged fuel. You have to reprocess to reuse this, even if you aren’t trying to breed, or you end up throwing away more fissile than an equivalent-power conventional reactor would need in total.

Enriched uranium for fast reactors may be feasible in source countries like Australia, Canada, Russia or Kazakhstan but reuse of materials is the best policy for others. Costs are relative and vary with the place, time and circumstances. The China currently has lowest costs and highest number of reactors under construction.

If the UK do not want any further reprocessing and only want to use up the plutonium stocks, they should include it in thorium pellets as the fissile feed and burn it in their AGRs and the future EPRs. They will avoid capital expenses of a FOAK reactor and get return on the money invested in reprocessing in the past.

Luke, Pu startup without the online processor will certainly be uneconomic. But low enriched uranium startup with a high burnup should be pretty decent – you can get well over 10 years fuel life which mostly makes up for the higher fissile charge. One of the advantages of the fast spectrum is that fission products aren’t such a big deal, and the bred plutonium is better fissile than the low enriched uranium startup. I guess this is getting nearer to a travelling wave reactor than an IFR.

Regarding the cladding, I’ve always wondered why IFRs have always suggested stainless steels and such for cladding. This seems like a case of reinventing the wheel. Why not use the zirconium based PWR cladding? That’s what is being used right now, it works fine, no low melting plutonium eutectics. All the nuclear giants are still investing in better zirconium based claddings, recently we’ve seen the oxygen dispersal strengthened zirconium claddings from the French and Russians. With no water in the core, zirconium’s primary safety issues (hydriding, oxidising, hydrogen evolution) disappear.

Found the ref. on (un)economics of IFRs in once-through mode

http://www.osti.gov/bridge/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=5134577

Chang & Till wrote

LMR = liquid metal (cooled) reactor

Luke, I don’t see where the evidence is. I just see some very low fuel cycle costs in general with some bold assertions by IFR people begging for an online processor unit. Even if I don’t try to read between the lines.

In India, the per MW costs of the PFBR and the Russian design VVER (both in advanced construction stage) are similar. It must be the same in Russia. Some would call the RG Plutonium costlier. Others would call it recycling of waste. Without recycling in fast reactors, the uranium peak may be close. There are news predicting it and studied statements against it. With fast reactors, you are safe for centuries.

I wonder if the 10% zirconium is to increase the softening range of the fuel, rather than to lift the melting point as stated in the book. As a viscous material against the steel cladding, it would have less power to dissolve the stainless steel. Similarly, a viscous alloy would be more able to accommodate the bubbles in the metallic foam.

As temperature increased during some extreme event, the hotter and thus softer foam would be more able to expand and provide the proven self-limiting safety response of the IFR.

I note that the EBR2 fuel also contained zirconium, perhaps providing the proof of concept.

Roger, the melting point itself doesn’t appear the basic problem. Wikipedia has a cool graph of the different phases of the actinides:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/5/53/ActinidesLattice.png

Uranium has a low temperature transition. Adding zirconium would increase that transition, causing the crystalline phase change related swelling to occur at higher temperatures, ie above normal operating temperature, which is what you want.

It also looks as if the crystalline change absorbs a lot of heat, just like actual phase change absorbs latent heat. That’s cool. I mean, it keep things cooler during a transient.

The metal fuel and metal bond are truely genial inventions. I wonder why it is not used more often. PWRs could use lead as a metal bond in the oxide fuel. There was some work on this but it doesn’t appear to have made it to commercial plants. It is really worrying that even modest innovations in existing reactors have a hard (and long) time to get into commercial operation,.

CyrilR gave an explanation of the role of zirconium, suggesting that it would raise the temperature of a phase change in otherwise pure uranium. This would have been apropos EBR2′s mainly-uranium fuel. However, I would also suggest that zirconium may be adding glassy bonds that impede transitions between crystalline phases.

IFR fuel is to contain 40 to 50% plutonium, which shows up as particularly complex in CyrilR’s link to the crystalline phases of the actinides, so the need to inhibit crystalline phase transitions increases.

In order to machine plutonium metal, bomb makers add about 5% gallium to ensure a workable material. In an article in Physics Today, we read that the plutonium alloy in weapons is thermodynamically unstable, in a state of suspended transition.

If Pu-Ga weapons-grade metal is to be turned into fuel in an IFR pyroprocess, the gallium would presumably accumulate at the anode along with iron from the cladding.

To avoid the sacrifice of good in pursuit of the best, you could have a CERMET (CERamic PuO2-METallic thorium) fuel. You will be sacrificing the fast fission of thorium as well accepting nearly 25% of O atoms. What you get is high melting (2115K) metal matrix and creation of U-233.

U-233 can be used as a metal with Uranium or thorium metals.

PS-A correction-Sacrificing the fast fission of uranium.

[…] These excerpts not only provide a fascinating insight into a truly sustainable form nuclear power; they also provide excellent reference material for refuting many of the spurious claims on the internet about IFR by people who don’t understand (or choose to wilfully misrepresent) this critically important technology. Click here for part 1 (metal fuels and plutonium). […]

@Jagdish proposes a fuel composite material of PuO2 in a matrix of Th metal.

The high neutron flux in an IFR would excessively increase the probability of Pa233 absorbing a neutron instead of decaying to U233. It would however make sense in a low flux reactor like CANDU. In fact the IAEA proposed such a mix as a good way to burn plutonium.

If an IFR were to be used to burn plutonium rather than breed it, the plutonium still belongs in the core, whereas thorium could be used in the blanket. Then in the pyroprocessing, the cheap, disposable thorium could be dropped out at the anode (if my guess at its rank in the electrochemical series is correct) whereas the precious U233 would travel on into the cadmium cathode. However this would not serve the self-sustaining intention of an IFR.

Roger, CANDUs are quite high flux in terms of numbers of neutrons. But their excellent thermalized spectrum reduces the losses to Pa233. And their low fissile inventory reduces the cost of buying the reprocessed Pu (it is expensive).

However a very fast spectrum also reduces the losses to Pa233, and what is more, the U234 produces from captures has a good fast fission profile. So it is not so bad for a fast spectrum, though the IFR’s high power density does gobble up more Pa233.

It should be quite feasible to breakeven on breeding with an IFR running on Pu-Th fuel. You could also have a hybrid cycle with some U238 in it to increase breeding ratio & denature the bred U233 to low enriched uranium levels. That would be a very proliferation resistant cycle.

As for reprocessing, I think you can also boil out most of the fission products in metallic form using a single stage distillation unit. That leaves all the actinides together – they’re all very high boiling.

If the single unit uses chlorides, themost volatile elements will be thorium and uranium. Plutonium and other actinide chlorides are close to lanthanides in volatility. They are best separated electrolytically by Pyroprocessing associated with IFR.

@CyrilR — it is good news is that U234 fissions well. Already enriched in any LWR fuel used as top up, it would otherwise accumulate in the IFR, as its cycling burns its way through the trickle of input actinides.

What might accumulate is any (non-fissile) fission product, or component of cladding metal, with an electrode potential that gets it swept into the cadmium cathode. Jagdish, you spoke of electrolytic separations, would you be able to link us up with a table of electrode potentials?

Roger – this reference has what you’re looking for:

http://fti.neep.wisc.edu/neep423/FALL99/lecture5.pdf

It has a table of Gibbs free energy which tells you where the different atoms will tend to go into. Cd, Fe, Mo, Nb, Tc, Rh, Pd go into the cadmium pool (anode). Actinides and Zr are electrotransported for recovery. More stable stuff such as Ba, Cs, Rb, Sr stay in the salt as chloride salt.

I wonder how the processor is cooled – surely some passive cooling system?

@CyrilR, thank you for the link. These figures are those in the book, presumably from the same source. In the book, captions refer to the values as kilocalories per mass, whereas here it is more clearly in kilocalories per mole of electrons. Converting to joules per coulomb, ie volts, shows the range of voltages needed to re-collect the elements for the core fuel at 500°C :

CmCl3 -2.77

PuCl3 -2.71

AmCl3 -2.69

NpCl3 -2.52

UCl3 -2.39

ZrCl2 -2.02

However the table refers only to the elements in the study, which would not include all of the fission products, nor all of the elements in the alloys in the LWR fuel, stainless steel etc. I wonder that with continuing recycling, unwelcome elements might accumulate. Magnesium, aluminium and beryllium come to mind. Quite possibly, the activation products would add minimal radioactivity, however spallation of beryllium may bleed tritium for example.

On the other hand, it would be neat if subsequent processing of chlorides were able to separate cesium (-3.81 V is too high for the pyroprocessor to separate it) and somehow return it to the core fuel, so that the long-lived Cs135 could be transmuted.

Unfortunately the pyroprocessing was carried out only on one batch of fast reactor fuel. Let us hope that Russia, China or someone else continues the good work. Indians are reluctant to even think about salt fuel, which is the medium for extracting TRU’s by electro-refining.

Magnesium will only be present in minute quantities in the sodium coolant and sodium bind, from sodium neutron activation. But magnesium forms a stable chloride that should stay in the salt electrolyte. Aluminium I don’t think is present at all in the IFR system. Beryllium might be present as minor fuel constituent, but its presence is beneficial to neutronics and fuel integrity. It reduces swelling, rod surface oxidation, improves delayed neutron fraction, etc. Zirconium is convenient to recover since a goodly amount is needed in the fuel.

Cesium chloride could probably be recovered by vacuum distillation (ORNL developed this techology decades ago for the MSRE). This is probably the simplest way to go; the salt is already molten in the processo and need only be routed to a small single stage still.

I wouldn’t worry much about Cs-135, though. It’s a long lived beta emitter that doesn’t bioaccumulate.

Jagdish, pyroprocessing is being actively developed in Korea. From the Korean Atomic Energy Research Institute’s page on fuel cycle development we learn:

Given Korea’s commitment to nuclear technology development I think this is cause for optimism.

This is good news. Bulk of reactor construction is now in Asia. Advantage research should also logically be at the same places. Fast reactors and pyroprocessing, the main components of the IFR are the next big step in nuclear power development. Fast reactors in Russia, China and India and pyroprocessing in Korea could lead to IFR development. Let North America, Europe and even Japan have a long breather of a decade or two.

One cannot simultaneously reduce the volume and the specific heat generation. Indeed, they are opposed. Concentrating fission products (which generate almost all the decay heat) by removing the 95% uranium bulk (which generates almost no decay heat) increases the specific heat generation.

Also, the fission products don’t go away – their total heat rate is fixed at a familiar declining rate, no matter what the volume.

The selling points for the hot processing “pyroprocessing” technologies are in the small physical equipment size & related cost, almost complete elimination of long lived wastes (waste-to-energy), high temperature operation allowing passive cooling (safe) and the use of shorter lived spent fuel, and lack of bulky secondary wastes creation.

It is likely that the fission products can be used to generate power, because they are sitting so hot in a molten salt bath. If the power or cooling fails, the higher temperature rise will remove heat passively.

I’m not very worried about long-lived fission products. The “worst” of these is Tc-99, which has about the same yield as Cs-137, but ~7000x longer halflife and ~4x lower decay energy, for a total activity ~28 000x lower. Cs-135 is ~10x lower still with ~11x longer halflife, a bit lower decay energy, but somewhat higher yield than Tc-99.

Sn-126 might represent a problem due to the 2,8 MeV gammas from its daughter Sb-126, but 230 ka halflife and low yield keeps the activity fairly low. Other LLFPs are even less of a worry.

MODERATOR

Speedy – BNC Comments Policy requires scientific refs to support your comment. Please supply tthem so others, not as knowledgeable may check out the information in more depth. Thankyou.

Technetium-99 is a high value industrial catalyst and corrosion protector. It’s best use is for nuclear applications where the slight radiation is no problem, for example nuclear primary loop and steam generator components (adding some Tc-99 in the alloys protects the alloys from corrosion).

Sources for my previous post:

Wikipedia on LLFPs:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Long-lived_fission_product

2,8 MeV gammas from Sb-126 comes from the ANL fact sheet on tin:

http://www.ead.anl.gov/pub/doc/tin.pdf

I’ve compiled a spreadsheet of fission products showing nuclides with halflifes >1d, >10d, >1a, long lived and the final stable isotope for each atomic number along with thermal yields for U233, U235, Pu-239 and Pu-241:

http://home.broadpark.no/~efredri/fission%20product.ods

Feel free to share it. There are two omission from this spreadsheet, meta-states (e.g. Sn-121m) and the effects of neutron capture (e.g. Cs-134 is not produced directly since it’s shadowed by stable Xe-134, but is produced with capture from Cs-133).

Halflifes vary somewhat between sources, I’ve used this chart:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NuclideMap.PNG

Yields are from here:

http://www-nds.iaea.org/sgnucdat/c1.htm