Guest Post by Tom Blees. Tom Blees is the author of Prescription for the Planet – The Painless Remedy for Our Energy & Environmental Crises. Tom is also the president of the Science Council for Global Initiatives and a board member of the UN-affiliated World Energy Forum [wef21.org]. Many of the goals of SCGI, and the methods to achieve them, are elucidated in the pages of Blees’s book. He is a member of the selection committee for the Global Energy Prize, considered Russia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize for energy research. His work has generated considerable interest among scientists and political figures around the world. Tom has been a consultant and advisor on energy technologies on the local, state, national, and international levels.

Guest Post by Tom Blees. Tom Blees is the author of Prescription for the Planet – The Painless Remedy for Our Energy & Environmental Crises. Tom is also the president of the Science Council for Global Initiatives and a board member of the UN-affiliated World Energy Forum [wef21.org]. Many of the goals of SCGI, and the methods to achieve them, are elucidated in the pages of Blees’s book. He is a member of the selection committee for the Global Energy Prize, considered Russia’s equivalent of the Nobel Prize for energy research. His work has generated considerable interest among scientists and political figures around the world. Tom has been a consultant and advisor on energy technologies on the local, state, national, and international levels.

Roads Not Taken

Those who grew up during the years of the Cold War will probably never forget the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, a time when two superpowers came perilously close to unleashing all-out nuclear war. Several of John Kennedy’s generals were purportedly advising an attack at least on Cuba, if not on Russia itself. Kruschev was likely receiving similarly bellicose advice from some of his advisors. The fact that these two men took the decision to stand down brought the world back from the precipice.

But this harrowing incident was certainly not the only time that those two nations came close to initiating nuclear Armageddon. Yuri Andropov was also reportedly urged at one point by his military advisors to attack the United States, but refused to listen to them. And then there have been close calls caused by malfunctioning early warning systems, sometimes in the USA, sometimes on the other side. The average citizen was blissfully unaware of these near misses, and will likely never know about them except from hearsay or historical reporting many years after the fact.

But there is another nuclear road that was not taken. Ironically, the failure to take that road can lead to global catastrophe for both humankind and many of the species with whom we share this planet. This time the problem is not nuclear war but the threat of climate change, and nuclear power can be the solution.

This article is being written on the one-year anniversary of the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami that devastated communities in northeast Japan in March of 2011. Though nearly 16,000 people were killed in the tsunami and over a million buildings were destroyed or damaged, if one were to ask nearly anyone outside Japan about the Tōhoku earthquake it would likely elicit no recognition. But mention Fukushima and immediately people know which earthquake you’re talking about. For the press coverage of the nuclear accident at the Fukushima Daiichi power plant dwarfed the attention paid to the devastation wrought elsewhere by the tsunami.

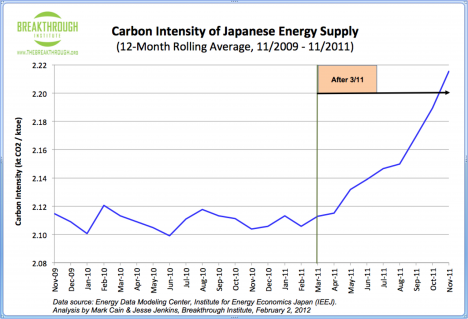

As a result of this phenomenon, Japan has taken nearly every one of its 54 nuclear power plants offline amid pressure to abandon nuclear power entirely. Since those power plants were supplying about 30% of Japan’s electricity, this has dramatically increased the country’s carbon emissions as it turned to fossil fuel imports to keep the lights on and the factories running. It has also created Japan’s first trade deficit in over thirty years, with an estimated cost of about $100 million per day for additional energy imports.

But the impact of the Fukushima accident reached far beyond Japan (Aside: can it truly be termed a “disaster” or “catastrophe” when there was not a single instance of radiation-induced injury to the public? Even among emergency workers at the plant there were only a few who are expected to have any radiation-induced health risks. One worker died, but it was from a heart attack and had nothing to do with radiation exposure.) Shortly before the accident, Germany had been arguing over whether to decommission their perfectly serviceable nuclear power plants in deference to political pressures from the Greens. Fukushima tipped the scales, consigning Germany to a future of more coal and gas burning and almost certainly more (ironically, often nuclear-generated) electricity from its neighbors. Some other European nations have likewise reacted to Fukushima by foreclosing the option of building any new nuclear power plants.

But the nuclear road not taken that was alluded to above was a far more consequential decision, and one that might without exaggeration be termed a disaster. Like many choices of great import, the decision to abandon a new type of nuclear power system was taken by a few people in key positions. History will not likely judge them kindly, though as in so many cases those who exercised the most influence remain for the most part nameless, unknown to those who were outside the process.

Filed under: IFR FaD, Nuclear | 17 Comments »

.png)