Guest post by DV82XL. He is a Canadian chemist and materials scientist (and regular, valued commenter on BNC).

Guest post by DV82XL. He is a Canadian chemist and materials scientist (and regular, valued commenter on BNC).

In the biggest gathering of world leaders short of the one that formed the United Nations, leaders from almost 50 states and other related organizations came to Washington, D.C., this week as part of the Nuclear Security Summit. The host, US President Barack Obama said the joint action plan agreed at a summit in Washington would make a real contribution to a safer world. The plan calls for every nation to act to keep material out of terrorists’ hands. This meeting and the action plan it created is a thinly veiled attempt to concentrate power in the hands of those that currently enjoy it.

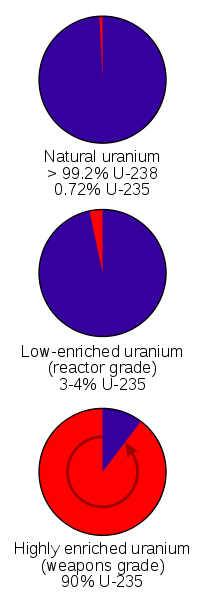

First let’s make one thing very clear: a subnational group (terrorists) cannot and never will be able to manufacture a nuclear weapon. This is true even if they were handed weapons-grade fissile material up front. Whatever the reasons for this drive to strip every last gram of highly enriched uranium (HEU) from every country in the world that is not one of the existing nuclear weapon states (NWS) ‘terrorists’ stealing this material to fabricate a weapon, is not one of them. HEU is treated by all countries that own it as if it were more valuable than gold, a critical mass worth of HEU represents a huge investment to a country who acquired it for a purpose, and as part of a program, the fact remains that this stuff is controlled and accounted for very closely, which is why it has never showed up on the black market.

Let’s examine the first contention. While it is true a gun-assembled HEU uranium bomb is conceptually simple, building one that will work, is not and requires more resources than an extranational group can muster. A careful review of the facts suggests that there are technical obstacles to such an attack that are insuperable, and there is no evidence that any terrorist group currently possesses the expertise necessary for a nuclear effort. Claims that this is possible glosses over the difficulty of finding the kinds of highly qualified experts such a project would need and omits real consideration of at least a dozen points in the process where something could, and very likely would, go wrong that would bring the whole project to an end.

But let’s take it one step further. Any terrorist group that decided it wanted a nuclear weapon would first reason that the easiest way would be to steal or buy a device from a nuclear weapons state. They are quickly disabused of this idea because it is impossible for them to do so. Why do we know this? Because it hasn’t happened. If it was that easy there would be no running planes into buildings; there would already be a radioactive crater in Manhattan.

So they are left with building one. Now they have three issues: HEU which is no easer to obtain than a complete device, finding people that know what to do with it, (and are willing to cooperate) and setting up some place on Earth where the host government won’t have instant diarrhoea at the thought of a group they had no control of holding a nuclear device inside their borders.

Looking at it like this, the terrorists can see that it would require a very unlikely series of events and a great deal of effort, and pressed for information, any high school physics teacher will tell them there are no guarantees the damned thing will work. Result, scrap Plan A and go to Plan B: Hijack four widebody aircraft…

Fretting about “loose nukes” has been a popular topic of discussion in anti-proliferation circles, but a solid decade of this hand-wringing about terrorists’ hypothetical nuclear weapons has revealed no new evidence that any such group is any nearer to realizing this ambition,

So why then is everyone getting their shirts in a knot over this? There is a real concern that the world is standing on the cusp of a nuclear proliferation cascade, and the current NWS want to reduce the possibility that any other nation will acquire these weapons. It’s not terrorists stealing Chile’s HEU that is the worry; it’s that somewhere down the road the State of Chile may decide it needs a weapon.

At the root of this thinking is the Bush era, Pentagon commissioned study that argued climate change could lower nuclear security possibly even leading to war. The issue was not just the spread of nuclear weapons. The issue was the spread of nuclear weapons in the context of a global environment more conducive to conflict and strife, following on from a lowering in the world’s carrying capacity.

The report explored how such an abrupt climate change scenario could potentially destabilize the geo-political environment, leading to skirmishes, battles, and even war provoked by resource constraints such as: food shortages due to decreases in net global agricultural production, decreased availability and quality of fresh water and disrupted access to energy supplies .

The report explored how such an abrupt climate change scenario could potentially destabilize the geo-political environment, leading to skirmishes, battles, and even war provoked by resource constraints such as: food shortages due to decreases in net global agricultural production, decreased availability and quality of fresh water and disrupted access to energy supplies .

These the report argued, could cause tensions to mount around the world, which would lead to the adoption of one of two fundamental strategies: Nations with the resources to do so may build virtual fortresses around their countries, preserving resources for themselves. Less fortunate nations especially those with ancient enmities with their neighbours, may initiate struggles for access to food, clean water, or energy. Unlikely alliances could be formed as defence priorities shift and the goal is resources for survival rather than religion, ideology, or national honour.

Clearly it is believed by the current NWS that within this context, a tipping point leading to a proliferation cascade is a real possibility. This is the unstated underlying reason for the rush to secure as much HEU from around the world as possible, and will be the driving force to push through a fissile materials treaty in the near future. However this path is not without its consequences, nor is it as pure in its motivations as it might seem.

There are few things as desperately misunderstood as nuclear weapons, and their place in the broader geopolitical picture. This is in general due to the fact that public perceptions about this weapon system are a product of Cold War propaganda, and their treatment in fiction, both on the page and on the screen. These ideas persist even though the devices, the doctrines, and the world itself have changed radically since those times.

Most believe that the military role of nuclear weapons is to destroy cities. This is understandable, since that was what the only two used in war did. Indeed at the beginning this was the role of these weapons because with the crude technology of the day, a city was the smallest high-value target that a bomber or an ICBM could reliably acquire. Once this process of targeting each other’s cities between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. started, a stalemate swiftly developed, even though it became clear to both players rather early on, that the usefulness of this strategy had passed.

What was realized was that the real military value of nuclear weaponry was in a tactical role. Low yield nukes, delivered by medium –range missiles, or attack aircraft were the ideal way to prevent any large scale manoeuvres, (like a massed column of armour) or a sea-born invasion from occurring, and that any attempt to carry out operations on a wide, dispersed front, could be countered easily by defence-in-depth tactics. Thus the real nuclear stand-off was between the word’s military powers, rather than by threatening dense civilian populations.

This situation persists to the present. The fact is that no nuclear power would consider an attack another because they could not follow it up with an invasion and there would likely be a counterstrike. As well, no nuclear power would prosecute a nuclear attack on a non-weapons state, without risking becoming an international pariah, and again with the risk of enduring reprisals in kind. Thus nuclear weapons ultimately stand as defensive assets, almost useless in an offensive role. And indeed this is reflected in both the designs and doctrines of these systems in the smaller NWS.

This brings us back around to the current nuclear summit and the obsession with weapons-grade uranium and plutonium in the hands of smaller states, and the threat of climate change. If the role of nuclear weapons is seen by smaller powers as a military tool to counter large conventional forces mounting an invasion, or even to counter the projection of might from something like a carrier task force, this renders conventional military power useless as a threat. The current members of the NWS club are also field large conventional forces as well, and several have shown no compunction in using them to further diplomatic or economic ends. The possibility of having those forces rendered useless by a major round of proliferation, particularly in regions where they currently exercise domination and especially in the event that climate change alters the relative value of those same regions, is obviously unpalatable. In short, this is not about keeping the peace, but maintaining the status quo in the international power structure.

There is a price to pay for this however. Putting an end to commercial use of HEU is going to cause problems of its own and these are not insignificant. In fact several countries are balking at the prospect and have said as much at the summit. Reading between the lines, it is also clear that their intransigence will be addressed at the G8 meeting later this year.

The two most widespread uses of HEU are as research reactor fuel and as targets for the production of medical and industrial isotopes. While few in number, test reactors, used for experimental fuel development for NPP, also need to be very powerful, and thus need enriched fuel. In addition to research and test reactors, there are also critical assemblies, subcritical assemblies, and pulse reactors that use fuels containing HEU. Critical and subcritical assemblies, for example, are typically used for either basic physics experimentation or to model the properties of proposed reactor cores, while pulsed reactors, are used to produce short, intensive power and radiation impacts.

High energy neutron beams can be used for some sorts of radiotherapy and for imaging very dense materials, an application of use to several industries. All this will end except in those places under the control of the governments of the NWS. Arguments that most of these applications can be redesigned to use low flux radiation are specious, as the throughput of these processes is sharply reduced. The NRU reactor, in its day could supply much of the world with medical isotopes, when it restarts, using LEU targets, it will supply Canadian needs only.

In short, activities that depend on high flux neutrons, in medicine, industry, and research, will be the private domain of those states that deploy nuclear weapons. This includes the development of nuclear energy, and power reactor design, which requires access to high flux neutrons to qualify material and assemblies, essentially closing the door on any further competition, (as well as the end of CANDU development) putting the NWS in virtual control of nuclear energy all over the globe, further extending their economic hegemony for the foreseeable future.

This is the real story here. The facts are all in front of us, and available to anyone who wishes to explore them. They are not that complex, and the geopolitical, economic and military ramifications of nuclear technology, and the impact of policy on them, are surprisingly simple to understand by anyone that takes the time to background themselves in these topics. I encourage everyone to do so as I believe you will draw the same conclusions I have in these matters.

Filed under: Nuclear

.png)

But let’s take it one step further. Any terrorist group that decided it wanted a nuclear weapon would first reason that the easiest way would be to steal or buy a device from a nuclear weapons state. They are quickly disabused of this idea because it is impossible for them to do so. Why do we know this? Because it hasn’t happened. If it was that easy there would be no running planes into buildings; there would already be a radioactive crater in Manhattan.

Come on Barry, that’s a bit Post-Hoc-Ergo-Propter-Hoc isn’t?

“After, therefore because of it.”

Planes in 9/11, therefore nukes never. I’m not sure why the second half of that sentence applies? Yes it is difficult, but impossible?

It sounds a bit like special pleading.

Sorry that should be “Come on DV8″…. I should have recognised Barry wouldn’t weave such special pleading into an article post.

eclipsenow – Even during the fall of the U.S.S.R., with several secession states suddenly finding themselves in control of nuclear warheads, and rise of organized criminal enterprises in that region, no nuclear weapons made it to the black market. The reason is that these things are as valuable as they are dangerous – they represent a huge investment by the state that built them, and they are treated as such. Not only are they valuable as weapons, but they also are high-value bargaining chips, and they are treated as such by those that own them.

There is as the fact that all nuclear warheads have a ‘best before’ date after which they need to be serviced by an organization equipped to do so, and unless deployed to operational status, are not fully assembled while stored. This would make theft of a full working device very difficult, and using it almost impossible.

Diversion of existing nuclear weapons, in working condition, to the hands of a subnational group is just not a credible threat.

DV82XL,

Thank you for this enlightening contribution. I am confident your assessment is correct. However, I wonder what is the best way to proceed from here. Are there just two options or is ther some other option. The two options I see are:

1. only the existing nuclear weapons states can posesss HEU; OR

2. continued increase in the number of states that have nuclear weapons, with the number of states that possess nuclear weapons increasing at an accelerating rate.

Are there other practicable alternatives? What are they?

When I noticed US Energy Secretary Chu sitting behind Obama I wondered if this summit was really to soften public opinion about greater shipments of LEU. Later that would include start charges for Gen IV reactors and movement of nuclear batteries. I suspect Chu has told Obama the US must increase nuclear generation capacity and the public needs greater assurance on handling of civilian nuclear material. The necessary first step is going through the motions on military grade material.

I think they said there will be 90 tonnes of plutonium made available. What happens to that?

Peter Lang – Nuclear warheads are too precious to give away or to sell, too precious to “waste” killing people when they could, held in reserve, make the United States, or Russia, or any other nation, hesitant to consider military action. What nuclear weapons have been used for, effectively, for 60 years has neither been on the battlefield nor on populations; they have been used for influence.

Even from a terrorist’s perspective, the most effective use of a nuclear bomb, (in the highly unlikely event one of these groups acquired one) would be for influence. Possessing a nuclear device, if they could demonstrate possession, (and there are ways they could) without detonating it would give them something of the status of a nation. Threatening to use it, may appeal to them more than expending it in a destructive act. Even they may consider destroying large numbers of people and structures less satisfying than keeping a major nation at bay.

When last we saw a world without nuclear weapons, human beings were killing each other with such feverish efficiency that they couldn’t keep track of the victims to the nearest 15 million. Over three decades of industrialized war, the planet had averaged around three million dead per year. Many wars, small and large, have been fought since Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However the Major Powers found ways to get along because the cost of armed conflict between them has become unthinkably high.

The bald fact is a world with nuclear weapons in it is a frighting place to think about. The industrialized world without nuclear weapons was a scary place for real.

Instead of fantasies about a nuke-free planet where formerly bloodthirsty humans live together in peace, what the world needs is a safer, more stable nuclear umbrella. That probably means more nations with nuclear weapons, holding for their own defence. It’s interesting to note that aggressive politicians tend to turn into tame sane cautious ones as soon as they split atoms. Whatever their motivations and intents prior, the strategic facts surrounding nuclear weapons dictate that warmongering leaders become peace-loving ones very quickly.

I know this is not a popular view, however it would seem that history reflects this interpretation more than it does the non-proliferation/nuclear disarmament rhetoric that has been driving current opinion on this subject.

Related to this topic, here is an article sent to me by SCGI’s Dan Meneley, which he wrote back in 1977. Still relevant today… (8 pages)

DV8 wrote:

I simply can’t agree. I’d far prefer to take my chances in a world where all nuclear weapons had been decommissioned and their radioactive materiel had been applied to peaceable purpose. Ideally, there would be no battlefield weapons at all, but one supposes that that really is utopian.

The problem with your analysis is that while it might have held for WW1 had they had nukes and delivery systems, (though this is far from certain, had the Nazis or the Soviets had them in the first months of Operation Barbarossa I shudder to think what would have happened. It’s also clear that at least some in the Pentagon in 1962 favoured using them as they had the tactical advantage.

And are we really sure that Israel or Pakistan won’t ever use them? Pakistan threatened just that in 1999 over Kashmir.

I simply don’t trust the state any state with such weapons.

I simply don’t trust the state any state with such weapons.

I don’t trust any state at all. But they have a lot less room to manouver in a world with nuclear weapons.

http://channellingthestrongforce.blogspot.com/2009/10/pax-atomica-prologue-im-posting.html

If no state had nuclear weapons or the systems to deliver them they’d have even less room to manoeuvre.

Recent experience in Iraq and Afghanistan shows that even when a big power goes up against a small and decrepit one, the results are not good for the big power. Everybody loses. This in a way is the strongest argument for nuclear devices. Had Saddam or Mullah Omar really been thought to have them (but not had them), maybe there wouldn’t be such a mess.

So it is even less likely that one large power could hope to subdue another large power, in the way that the Germans tried between 1939-45. The US failed to subdue Vietnam. Japan failed to subdue China. The US of course would have subdued Japan even without the bomb, but for political reasons, chose to use it.

Today, the trade and institutional restraints make a new conflagration with conventional weapons on a large scale unthinkable. Nukes are the one shot in the locker.

If no state had nuclear weapons or the systems to deliver them they’d have even less room to manoeuvre.

No Ewen, they’d have more. Specifically, they could wage a conventional war between the Great Powers (whoever they are) of the day which would be unthinkable if those states possessed nuclear weapons. The existence of nuclear weapons forces restraint.

Today, the trade and institutional restraints make a new conflagration with conventional weapons on a large scale unthinkable. Nukes are the one shot in the locker.

The existence of nuclear weapons has made it unthinkable, so we have institutions which reflect that reality. Remove that, and we’d see the next world war within a generation.

Thanks for interesting article.

The main declaratory nuclear issue from USA is Iran acquiring one. In one sense Iran is a failed state, they can’t conduct a democratic election. I don’t see a big difference between a nation state such as Iran or North Korea and a terrorist organisation, ie. they exert systematic terror against their own populations. If Iran did acquire one can we rule out the possibility that they would pass it onto Al Qaeda for use against Israel, for example? Perhaps not but it is a worry.

This scenario is of more concern to me at the moment then the future climate change scenario. btw I searched for the Bush study mentioned by DV82XL, here it is:

National Security and the Threat of Climate Change (pdf 35pp). I haven’t read it yet.

@Ewen Laver:

counterfactual historical speculation is tangential to this thread but you write that you “shudder” to think what would have happened had the Nazis or Soviets had nuclear weapons in the first months of Operation Barbarossa. Berlin’s racial extermination and sujugation plans for what was to happen to the USSR sub-humans after Wehrmacht victory are documented, however.

There has often been a post-1945 tendency in states within the US orbit, especially in self-interested circles that believe in the essential benevolence of all means of capital accumulation, to hold to the theory of totalitarianism, viz. Stalin=Hitler. In AU, as you will be aware, Tories who more than a sneaking regard for Adolf invariably claim “that the Germans were just fighting (sic) for their country.”

When I was at school, total Soviet population losses in WW2 were said to be below 20m; that figure has now been revised to 27m.

Prima facie and from a Soviet standpoint of minimising harm to a civilian population, use of nuclear weapons on the advancing Wehrmacht might well have reduced that figure.

In your later post at 1629h you seem to be using the term “subdue”, a term used in conventional international warfare, to apply to Nazi policy. However, the comparison of life as lived under Nazi occupation in western and eastern Europe respectively reveals the exterminatory nature of what you call “subdue.” Hence the conflicts of the US, Japan, China, Vietnam are inappropriate comparisons.

For some reason, wordpress declined to activate my subscription to this thread. Here goes…

Turning the HEU issue into a shibboleth is not a good idea. The most likely way HEU is going to pass into the hands of terrorists is for a nuclear armed state to break down. In that case, HEU might be given or sold to terrorists. But what the terrorists would prefer in those circumstances would be nuclear weapons drawn from existing stockpiles. An existing nuclear weapon is just going to ne so much more reliable, than a made from scratch, untested, crude nuclear weapon, made by terrorists in some jungle lab. It would be far better, in the eyes of our terrorists, to acquire say, a warhead made in Pakistan, and built by following a detailed design and manufacturing instructions to a pre-tested warhead, acquired by Pakistan from China. Not that China would ever sell or give Pakistan details on how to build a nuclear weapon, of course. And not that any member of the Pakistani military would ever have the slightest sympathy with the goals and methods of terrorists, of if such a person did exist, would have access to the Pakistani stockpile of nuclear weapons.

The HEU shibboleth is likely to bite the future of nuclear power. The preferred fuel for LFTRs is pure U-233. It is possible to denature the core U-233 with U-238, but this would have some undesirable consequences, including the production of plutonium.

Would building LFTRs in nuclear armed nations lead to the acquisition of nuclear weapons by terrorists? I would argue that LFTR construction in the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Russia, China, India, Brazil. Mexico, Canada, Poland, etc., would not increase the likelihood that terrorists will acquire nuclear weapons. But if we don’t have anything to worry about, a whole class of academic experts would be out of their jobs.

@Barry Brook – Very valid observations by Dan Meneley, suspicions that NPP are latent bomb factories, and visions of them going up in mushroom clouds is very much a part of public perceptions, exacerbated of course by antinuke mendacity. Overcoming it has been one of the hardest parts of the process. In some regards both TMI and Chernobyl have helped a bit by showing what real accidents look like, and while they are still PR problems in their own right, they at least give us something to point to.

@Ewen Laver – Your attitude still stems from the perception of nuclear weapons as offensive, rather than defensive assets. A close examination of both history and fact shows that despite bellicose noises to the contrary, every nuclear state does maintain a de fato No First Use (NFU) doctrine.

quoting freely from Stuart Slade’s The Nuclear Game – An Essay on Nuclear Policy :

The reasons are simple: When a country first acquires nuclear weapons it does so out of a very accurate perception that possession of nukes fundamentally changes it relationships with other powers. What nuclear weapons buy for a New Nuclear Power (NNP) is the fact that once the country in question has nuclear weapons, it cannot be beaten. It can be defeated, that is it can be prevented from achieving certain goals or stopped from following certain courses of action, but it cannot be beaten. It will never have enemy tanks moving down the streets of its capital, it will never have its national treasures looted and its citizens forced into servitude. The enemy will be destroyed by nuclear attack first. A potential enemy knows that so will not push the situation to the point where our NNP is on the verge of being beaten. In effect, the effect of acquiring nuclear weapons is that the owning country has set limits on any conflict in which it is involved. This is such an immensely attractive option that states find it irresistible.

Only later do they realize the problem. Nuclear weapons are so immensely destructive that they mean a country can be totally destroyed by their use. Although our NNP cannot be beaten by an enemy it can be destroyed by that enemy. Although a beaten country can pick itself up and recover, the chances of a country devastated by nuclear strikes doing the same are virtually non-existent.

With that appreciation of strategic paralysis comes an even worse problem. A non-nuclear country has a wide range of options for its forces. Although its actions may incur a risk of being beaten they do not court destruction. Thus, a non-nuclear nation can afford to take risks of a calculated nature. However,a nuclear-equipped nation has to consider the risk that actions by its conventional forces will lead to a situation where it may have to use its nuclear forces with the resulting holocaust. Therefore, not only are its strategic nuclear options restricted by its possession of nuclear weapons, so are its tactical and operational options. So we add tactical and operational paralysis to the strategic variety. This is why we see such a tremendous emphasis on the mechanics of decision making in nuclear powers. Every decision has to be thought through, not for one step or the step after but for six, seven or eight steps down the line. So, the direct effects of nuclear weapons in a nation’s hands is to make that nation extremely cautious. They spend much time studying situations, working out the implications of such situations, what the likely results of certain policy options are.

Let me quote Carey Sublette’s nuclear weapons FAQ:

Sounds like a pretty trivial engineering problem to me once assuming sufficient HEU.

On that basis, it seems to me that HEU in the hands of terrorists does constitute a very credible threat that it would be turned into an effective bomb, and therefore very considerable efforts to restrict its availability are justified.

@Robert Merkel – this is the sort of half-truths that have plagued this debate from the beginning. The very passage you quote is typical in that it dwells on the issue of assembly time, implying that this is the critical element that must be mastered. It is not, nor has it ever been. In fact that part IS trivial, what is not is a host of other parameters that must be met.

Consider Little Boy, (which seems to be the standard in this debate) this was a very large device, and it was crew-served, requiring a trigger installed seconds before it was dropped. If these types of devices are so simple to make, why then were the earliest models made by the major powers so large and complex. Certainly their nuclear weapons complexes, stocked with some of the best minds available, and the resources of a state at their disposal could have done better than what is being suggested can be done by a clandestine group of guerrilla fighters working in difficult conditions.

This is what I mean when I wrote that much of what is being assumed on this subject is at odds with history and fact. Little in these terrorist-with-a-nuke scenarios adds up when examined closely.

DV2XL:

I actually think that a terrorist construction of such a weapon is plausible – IF 60 kg of HEU was just handed to them on a platter.

A HEU gun-type bomb is a very different thing in practice to a plutonium implosion bomb, which isn’t plausible for terrorists to make.

Nobody is saying that such a weapon would be small or lightweight – but it could be assembled pretty easily if you had the HEU, and would be vehicle-transportable.

Having an initiator neutron source is not plausible for terrorists – but you would still get some nuclear yield without one.

The Little Boy bomb was large – but it wasn’t really complex.

The reason why that bomb was only fully assembled at the last minute while on the plane to Hiroshima is that a bomb like that, with the HEU installed and with the chemical explosive propellant loaded, is dangerously susceptible to accidental detonation – which would give the full nuclear yield.

DV82XL:

I mis-typed your name above. Sorry.

Luke Weston – “Plausible” is one of the most misused words in the greater nuclear debate.

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. 2010. defines the word three ways:

1 : superficially fair, reasonable, but often specious

2 : superficially pleasing or persuasive

3 : appearing worthy of belief

Most plausibility arguments for this or that, in the nuclear domain tend to project the term as sense 3, but upon closer inspection it is valid only as sense 1. This is the case here.

“Not complex,” is another misinterpreted term. It does not mean crude. While a uranium gun-type device is conceptually simple, it has very high tolerances, and requires both precise timing, fine adjustment of the propellant and detailed measurements of the fissile load to work with any degree of reliability.

All one has to do is look at the magnitude of effort required to build the first Russian, British, and French bombs, even with information begged, borrowed or stolen from the Americans, and state-level resources, to realize that this is a project outside the scope of any subnational group.

DV82XL: As you know perfectly well, the first bombs tested by the United States, UK and the USSR were plutonium-based implosion weapon designs, which tells us nothing about the difficulty of building a HEU-based gun device.

As you know perfectly well, the first bombs tested by the United States, UK and the USSR were plutonium-based implosion weapon designs, which tells us nothing about the difficulty of building a HEU-based gun device.

What do you think the Hiroshima bomb was?

OK Robert Merkel – Then rather look at the effort required by South Africa which developed and built a small arsenal of gun-type fission weapons in the 1980s. The point being that it still took the resources of a State to proceed with this kind of programme.

At any rate it would seem that theWashington Times agrees with me. In an article entitled Obama admin hyping terrorist nuclear risk it states that a senior U.S. intelligence official dismissed the administration’s assertion that the threat of nuclear terrorism is growing. The official went on to say the administration appears to be inflating the danger in ways similar to what critics of the Bush administration charged with regard to Iraq: hyping intelligence to support its policies.

As well, the latest CIA report to Congress on arms proliferation suggested that the threat from nuclear terrorism had actually diminished.

That’s rather damning I’d say

Scientific American raises the issue of commercial viability of breeder reactors…

http://tinyurl.com/y29kown

“If we build 200 to 400 more reactors, then it’s definitely only 100 years of supply,” argues Hanson, whose company is the largest supplier of uranium fuel in the world. “Would you build a nuclear power plant with a 60-year lifetime with only 100 years of supply? I wouldn’t if I was an investor.”

Nevertheless, Areva has also sold all its mining operations in the U.S. “The U.S. is the most unfriendly place on Earth for mining,” Hanson says. “The grades [of uranium] are not high enough to make it worthwhile.”

But even low-grade uranium is cheaper to work with than reprocessing, according to critics such as physicist Frank von Hippel of Princeton University. “Recycling and reprocessing don’t buy you much in terms of uranium resource savings unless you go to breeders, which have not succeeded commercially.”

As von Hippel notes, to really take advantage of reprocessed fuel requires a new type of nuclear reactor: so-called fast breeder reactors that essentially create, or breed, their own fuel. There is only one problem: commercial versions of such reactors have not worked despite efforts for at least 60 years to improve them. “We have spent $100 billion trying to make them commercial and they still have safety, proliferation and cost issues,” says physicist Arjun Makhijani, president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. And Hanson agrees: “Fast reactors are not ready for prime time.”

Oh, and here’s another nasty little fact I didn’t know about reprocessing….

“But reprocessing can end up producing more waste. According to the DOE, reprocessing spent fuel ends up increasing the total cumulative volume of nuclear waste by more than six times—thanks to more materials being contaminated with plutonium—from a little less than 74,000 cubic meters destined for some form of repository to nearly 460,000 cubic meters. Reprocessing also results in radioactive liquid waste: the French reprocessing plant in La Hague discharges 100 million liters of liquid waste (pdf) into the English Channel each year. “They have polluted the ocean all the way to the Arctic,” Makhijani says. “Eleven western European countries have asked them to stop reprocessing.””

Makhijani tells a great many lies in service of the anti-nuclear cause. I wouldn’t trust any economic analysis from his organisatuion. Those are the folks who produced this dodgy report about being able to power N. Carolina with renewables:

http://www.ieer.org/reports/NC-Wind-Solar.html

OK. So the argument against breeder reactors is that they shouldn’t be developed because they haven’t been developed….

OK, so he wrote about renewables.

Rather than further character attacks (which I find just so boring and predictable on this blog lately), do you have links to a paper that proves his basic assertions wrong? I’m tired of being told “He’s not a guru you should listen to — try my guru instead!” Instead try Barry’s response to Mark Diesendorf during their great debate:

“How about answering the arguments?”

Finrod said

You assert that but I don’t see that it is. Certainly, for rational people, it ought to be unthinkable but not all people who run states are rational in the sense that most civilised people would understand the term. It’s hard to imagine for example, that the Bush administration was restrained from using small scale tactical nuclear weapons against Afghanistan or Iraq by the thought that other states would attack them with nukes (or any other weapon). They probably were aware that within America, such an approach would have been seen as barbaric even by many conservatives and have stripped the “war on terror” of all moral legitimacy.

We have seen recently though how a fairly minor ripple in trade settings can have very serious consequences for employment and this certainly would apply to any conflagration that got close to a point where deploying nuclear weapons was discussed. The world in 1939 was not nearly so interconnected as it is now. Even then, the Axis view that it could essentially sustain itself economically while fighting a war against the US and Britain and cut off from major energy sources such as coal and oil and the hard currency to buy the many things not produced within its borders was wrong. Now it would be bizarre. Minor skirmishes are viable, but even a less minor one — the war against Indochina for example — was seriously debilitating.

This, rather than possession of nukes, was the primary constraint. It’s hard to escape the idea that the driving force behind the acquisition is the domestic political value associated with being able to claim, that pace Vishnu: Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

That kind of godlike power attracts even more majesty to office than does painting your head of government building white and making it look like a palace fit for a god. Let’s face it, it you can’t claim the power to murder people in large numbers in a short space of time, need anyone take you seriously? And if you decline on the basis that it is “simply too terrible to contemplate?” are we not all supposed to applaud your humanity and reason?

Paraphrasing what DV82XL said:

that the consequence of nuclear weapons in the arsenal imposes a calculus that constrains military action

That may well be so, at least in some cases, yet we must set this risk against very serious possibility of someone deciding to call the other’s bluff. If, for argument’s sake, China with the necessary delivery systems attacked Japan and/or Taiwan with nukes, would the US nuclear capability be deployed? Probably not. Yet if the Chinese themselves figured that this would be the response their nukes would be offensive or gain them leverage.

The other point is this: there simply isn’t any good tactical reason to respond to a nuclear attack with retaliatory nuclear weapons. Politically, the impulse would be near irresistible but it only gets worse from there. So it only takes one somewhat unhinged ruling group to think they can sail a little closer to the wind than previously for a devastating set of consequences to follow. That’s a downside risk I don’t fancy, given that I regard other constraints as being more likely to restrain serious wars between the major powers.

Peter Lalor said:

That may well be so, but you’re abstracting. Stalin, like Hitler was clearly by 1941, a psychopath. Here was a man who said one death is a tragedy … a million deaths is a statistic. There can be absolutely no telling what he would have done with such power at his disposal — so there was a completely open-ended downside risk. Had he possessed the weapon and had Hitler known, it’s doubtful indeed that Hitler would have even ordered Operation Barbarossa. His focus would have been on acquiring the technology. In the interim, he’d probably have focused on strengthening his hand in Europe, which, with hindsight, would almost certainly have better served the longevity of fascism. Not a good result in my opinion.

The megadeaths in WW2 were a terrible price to pay for the human system failures that led to the rise of Hitler and Stalin. It’s what happens when we humans get stuff really wrong. Really, this failure’s genesis was in the breakdown of the system which controlled Europe up to 1914 and thus set up the ducks for the Russian Revolution, worldwide depression and WW2.

I’m not sure what point you make when you chide me for using the term “subdue”. I was thinking of colonisation or vassal state configurations when I used the term.

DV8

You’re being slippery and inconsistent.

From the article again…

“”We have spent $100 billion trying to make them commercial and they still have safety, proliferation and cost issues,”

Tell me, at what point of expense do we walk away from R&D into renewables? 100 billion? What’s the research budget into renewables up to in the USA hey? Sounds to me like a LOT more attention and money has been put into commercialising fast breeders, and they have still failed!

This is exactly your rationale against further R&D into renewables. We shouldn’t bother with further R&D into renewables because we’ve already spent so much and they haven’t delivered the goods (according to you anyway).

I’d love to see what 100 billion could do for wind & storage. Oh, and again for geothermal. And again for solar thermal. Have all renewable energy systems COMBINED had as much R&D funding as this one nuclear technology of breeder reactors?

DV8, if not at $100 billion, at what point do we pull the plug on wasting more money into an industry that just does not seem commercially viable? Try being consistent for a change!

Rather than further character attacks (which I find just so boring and predictable on this blog lately), do you have links to a paper that proves his basic assertions wrong?

Character attacks? Because I said he told lies about energy systems in support of renewables and in opposition to nuclear power? When you’re prognosticating on energy systems, that’s a damn serious character flaw, and needs to be brought to general attention.

Anyhow, there were a number of posts on the subject on this blog, although I don’t recall which thread. Just have a hunt around for comments shortly after the study was released. There’ll be plenty of stuff there.

Nevertheless, Areva has also sold all its mining operations in the U.S. “The U.S. is the most unfriendly place on Earth for mining,” Hanson says. “The grades [of uranium] are not high enough to make it worthwhile.”

Of ,course it’ll be uneconomical for the U miners if they’re spending more than their rivals to extract a given amount from poorer grades of ore. That doesn’t mean that it’s uneconomical for utilities to operate power plants with U from lower grade ores, just that there’s no point spending more than you have to until it becomes necessary. Fuel costs are a small portion of the operating costs of a NPP.

eclipsenow – I am not being slippery and inconsistent. I just don’t take your uninformed and sophomoric arguments seriously.

@Ewen Laver:

You assert that but I don’t see that it is. Certainly, for rational people, it ought to be unthinkable but not all people who run states are rational in the sense that most civilised people would understand the term.

The leaders of ‘rogue states’ tend to be far more pragmatic in relation to their long-term personal interests than their propaganda and doctrinal justifications would suggest.

Well, DV8, I’m glad you came back with so much information as to R&D for various energy types and proved that breeders have been drastically under-funded compared to all the trillions put into renewable R&D! Well done! 😉

So I guess I’m left with NO ACTUAL INFORMATION rebutting the SCIAM points on breeder expense, and am left with their word as the last word. Well done all.

eclipsenow, if you listen to armchair judges like von Hippel from Princeton, then they’ll tell you “We have spent $100 billion trying to make them commercial and they still have safety, proliferation and cost issues”. If you listen to the folks from Argonne National Labs who actually worked on the R&D, they’ll you that safety and proliferation issues of designs like the EBR-II vs oxide-fuelled variants are essentially solved (refer to 1986 tests, pyroprocessing). I’ll leave it to you to judge which source is more credible on these matters of engineering and physics. As to costs, there are plenty of reasons to suspect a design like the S-PRISM will be cost effective, but let’s build an IFR and find out.

Ewen Laver – We cannot stuff this demon back into Pandora’s Box. Attempts to do so can be shown to be futile. ‘Going to zero’, as the antinuclear weapon cognoscenti put it, is a deceptively simple notion; just about everyone who knows nuclear weapons agrees it would be wickedly difficult to achieve.

That’s because it would require a sea change in a dizzying array of defence matters, ranging from core strategic policies to highly technical weapons programs. To fully grasp the political and military implications, consider what would have been involved had the great powers of the 19th century decided to abolish gunpowder.

Past efforts have foundered. A 1946 plan named after the American financier Bernard Baruch died partly because its scheme to have a powerful international agency control nuclear technology required the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council to give up their veto power on some nuclear matters. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, 41 years old now, has proved ineffectual in moving the world toward nuclear disarmament.

Even if arsenals are reduced to zero scientific and engineering knowledge cannot be expunged from mankind’s memory, the potential to build weapons will always exist.

Nuclear conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union was a prospect so harrowing that American and Soviet leaders recognized it was untenable, even as they planned for Armageddon. They possessed some 70,000 nuclear warheads between them in the 1980s, but the weapons were under firm control and neither side dared risk the retaliation that a first strike would draw. The balance of terror, in effect, neutralized nuclear weapons.

“We have seen recently though how a fairly minor ripple in trade settings can have very serious consequences for employment and this certainly would apply to any conflagration that got close to a point where deploying nuclear weapons was discussed. The world in 1939 was not nearly so interconnected as it is now. Even then, the Axis view that it could essentially sustain itself economically while fighting a war against the US and Britain and cut off from major energy sources such as coal and oil and the hard currency to buy the many things not produced within its borders was wrong. Now it would be bizarre. Minor skirmishes are viable, but even a less minor one — the war against Indochina for example — was seriously debilitating.”

In the world of 1939 several power blocks (the British Empire, isolationist USA, Nazi Germany with its virtual barter system among eastern European states, the deeply isolated USSR…) had spent a decade drifting into protectionism and autarchy. This was in contrast to the globalist policies in force during the Pax Britannica of 1815-1914. Pax Britannica and Pax Atomica both resulted from the implicit threat of overwhelming force capable of negating the defences of most or all Great Powers. When that condition exists, Great Power worlds are virtually non-existent. When it does not, endemic Great Power wars are the norm. Integrated global institutions can and will break down in a multi-polar world without dominating threat such as nuclear weapons.

What do you think the Hiroshima bomb was?

It was the first 235-U bomb, and it never had a test as such. The first use was the test. I have read that the reason they believed they could proceed without a test was the absence of any neutron-emitting isotope like segrium, aka plutonium-240. Is that not true?

(How fire can be domesticated)

My apologies. Great Power worlds should read as Great Power wars.

We do have an historical precedent DV8. During the Tokugawa era in Japan, guns were progressively abolished as the ruling elite decided that they gave the lower orders just a little bit too much comeback. Until the Americans showed upo, the policy was effective.

More seriously though, you are right — the genie (in this case technical know how) can’t be put back into the bottle, which is not at all the same thing as saying that we can’t ignore the existence of the genie. We also know how to make devastating chemical and biological weapons (which could probably do even more harm to long term human interests than nuclear weapons deployment) but as far as I am aware, the major powers and even most of the minor ones don’t keep them in a state of readiness to frighten each other.

I’m rather glad they don’t.

The broader question is this: If tomorrow the USA unilaterally said: we’re out of the nuclear weapons game. As of today we begin decommissioning all nuclear weapons and by 2020 there will be no such devices in any state of readiness within our jurisdiction — would they be worse off in absolute or relative terms? Nope. They can still deliver plenty enough deadly force at a distance to have a credible deterrent and they have a compelling argument to insist others do likewise, whether they ultimately do or not.. They could insist that states like Pakistan and India and Israel also eschew such weapons which would be a big contribution to a safer world.

GRLC, I understand that to be the case, but there was another reason Little Boy was not ‘just-in-case’ tested. That was it was such a damnable hard job to get the super-enriched U in sufficient quantities (some 65 kg from memory) using their diffusion method. With Trinity by comparison, they wanted to make sure the timing of their radial compressive explosives would actually work, and Hanford was doing a decent job by then at breeding more Pu.

Ewen Laver – Go back and read what I wrote above about the role of tactical nuclear weapons. Conventional forces, no matter how large or well equipped cannot prosecute a successful attack against nuclear bombs. It is how the Red Army was held back in Europe for many decades by a force that was a fraction of their size.

Nuclear weapons are attractive to smaller states because they are a very inexpensive way to keep from being invaded. That’s the only reason they want them. Don’t buy into the propaganda that they want to nuke London or New York, that is not a creditable threat from some nation like Union of Myanmar (who may be the next to arm with nukes) or Iran, that’s just BS fed to the masses.

You are still working from flawed assumptions, please look deeper into things and you will see that the real picture is very different than what we have been taught to believe.

DV8 wrote:

“The balance of terror, in effect, neutralized nuclear weapons.”

Post-Hoc again DV8. A documentary “Countdown to Zero” is coming out soon, by the people who made “Inconvenient Truth”. It documents how WW3 was only avoided by sheer chance on a number of occasions.

Computer war-game tapes being loaded and mistaken for the real thing, Russian subs with communications problems unable to receive instructions from command voting 2 to 1 not to nuke America, and a dozen other crisis scenarios have played out without the public’s knowledge.

Hopefully after this documentary the general public will not be as relaxed about the potential for disaster as you are. Pro-nuclear advocates will need to contend with a public much more informed about these matters. The documentary apparently lists far more events than the following wiki.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ww3#Greatest_threats

During the Suez Crisis of 1956, Soviet Premier Nikolai Bulganin sent a note to British Prime Minister Anthony Eden warning that “if this war is not stopped it carries the danger of turning into a third world war.”[1]

The Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 is generally thought to be the historical point at which the risk of World War III was closest[citation needed], but there have been other events that historians have listed as close calls to World War III.

On 26 September 1983, only 25 days after the downing of Korean Air Lines Flight 007, a Soviet early warning station under the command of Stanislav Petrov falsely detected five inbound intercontinental ballistic missiles. Petrov correctly assessed the situation as a false alarm, and hence did not report his finding to his superiors. Petrov’s action likely prevented World War III, as the Soviet policy at that time was immediate nuclear response upon discovering inbound ballistic missiles.[2]

During Able Archer 83, a ten-day NATO command post exercise starting on November 2, 1983, the Soviets readied their nuclear forces and placed air units in East Germany and Poland on alert. Many historians believe this exercise was a close call to a start to World War III.[3]

On 12 – 26 June 1999, Russian and NATO forces had a standoff over the Pristina Airport in Kosovo. In response, NATO commander Wesley Clark demanded that British General Sir Mike Jackson storm the airport with paratroopers. Jackson is reported to have replied, “I’m not going to start the Third World War for you”.[4]

CIA original operative, Miles Copeland, claimed that in the future, World War Three will kick off when “Soviet Russia” dupes the United States and Israel into waging a self-destructive war with the Muslim/Arab world[5].

Wikipedia and antinuke propaganda – really son is that the best you can do?

You have already established with your breathless ‘Black Swan’ sightings that you lack the capacity to weight what you read critically, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that you wouldn’t be capable of treating this topic any differently.

I know you are going to think I am just insulting you rather than addressing your concerns, but you show no analytical thought with these posts. Ewen Laver, who I almost never agree with, at least presents a considered POV, you just find the first contrary reference, and throw it in my face like a challenge, but without bothering to examine it yourself beforehand. I’m not here to do your reading for you, and then explain it back.

Marshal proper arguments and I will engage with you – presumptuously flinging poorly researched references at me demanding I answer them as if they were credible, and you will get silence.

Gosh DV8 … I thought we mostly agreed …

I am wondering if you could clear something up for me though. Is it your opinion that the practical security of the United States or its apparent allies would be prejudiced if they didn’t have deployable nuclear weapons?

I can see why smaller states like North Korea, Israel, Iran and so forth might think such weapons would be handy. As I said above:

Had Saddam or Mullah Omar really been thought to have them (but not had them), maybe there wouldn’t be such a mess

But the US? The UK? France? Russia? That simply has to be wrong

I’d just like to see if we can establish more precisely why you seem so exercised by the value of nuclear weapons in the hands of large otherwise well-armed states.

Ewen Laver – Of course there is no reason for them to maintain huge arsenals of the things, which is why the States and Russia are happy to dial them back. However they also need nuclear weapons to act as a deterrent to any one that could offer them a similar threat, if their conventional forces can’t attack another nuclear armed country.

The question you should be asking is why keep a large conventional force on the payroll in a world with nuclear weapons.

DV8,

Kim Beazley, our former Defence minister, has addressed the Lowy institute over various crisis during the 80′s with extreme concern.

More recently our former Foreign Minister, Gareth Evans, has presented an 80 minute talk at the University of Queensland explaining how to motivate international action on these matters, especially in the context of disarmament.

When it comes to nuclear disarmament, solutions to international conflict, even bringing a halt to mass atrocities, the lament is often a lack of ‘political will’. So how do you turn ideas into action in international decision-making? That’s the topic of the University of Queensland Centenary Oration delivered by Gareth Evans.

http://www.abc.net.au/rn/bigideas/stories/2010/2862453.htm

If you have half an ounce of integrity you’ll listen to this podcast, and then watch the movie when it comes out, and try and respond here.

Try and address the FACTS, as right now your own lack of concern appears to derive from the certainty of dogma. You sound like an inflexible old man too tired to be bothered by the details of history.

A new groundswell of information and alarm over these matters is coming. I’ll enjoy the ‘fallout’ as dogmatists such as yourself have to deal with the reality of history.

Your boring, predictable routine of sneering without substance will simply not suffice as the general public become more aware of the dangers these weapons pose and the catastrophes we’ve only narrowly avoided.

I cheer on your patronising blasé attitude — it will just do ‘your pro-WMD cause’ so much more damage. Good luck with that. 😉

DV82XL:

I wonder whether you could answer a few technical questions relating to the subject of your post?

1) I find your view to be reassuring and reasonably convincing that terrorists are extremely unlikely to be able to create a nuclear bomb. However, whether he really believes it or not, Obama has expressed the view that terrorists DO represent a nuclear threat. This expression has potentially important political consequences. To the extent that these may impact adversely on the rapid deployment of civil nuclear power, it becomes more important to emphasise that any threat that does exist can only come from theft of already assembled weapons or, less likely, of highly enriched uranium. As these would be neither available nor assessible from NPPs, it seems to me that it would be better to emphasise this point than to rule out the terrorist threat altogether. Do you agree or have I somehow got the wrong end of the technical stick?

2) If terrorists were to construct nuclear devices (rather than steal prefabricated weapons), what is the likely scale of damage they could do? My guess, only informed by fairly superficial reading, is that, at worst, it would be unlikely to be more than ten times worse than the consequences of the Twin Towers. However, were they to detonate a few pre-made atomic bombs, I would guess that they could obviously do at least one hundred times more damage than that caused by their earlier attack on New York. It seems to me, on the basis of risk analysis, that even this is trivial compared to threat to civilisation posed by AGW. As one who believes that civil nuclear power is the only realistic prospect that we have for escaping this threat, I confess to being fairly laid back about terrorists and nuclear weapons/devices. In your opinion, am I correct to be so?

3) To the extent that nuclear war has the potential to do anything like as much damage as AGW, I think one has to think nuclear winter. Can you comment upon the numbers and types of weapons that would have to be exploded to create effects that mimic the consequences of super volcanos? I have read that as few as 50, exploded over cities, might do the trick. Is this likely? Would these have to be thermonuclear as opposed to atomic weapons? If so, how much more difficult is it to construct the former once one has acquired the technical knowhow to create the latter?

To the extent that a proliferation risk is real, and I don’t think it can be entirely dismissed, it depends upon the spread of necessary skills and knowledge and the financial ability to put them to use. Rapid and widespread deployment of civil nuclear power is almost bound to equip an increasing number of nations with these knowledge and skills bases and thus increase their potential to make nuclear weapons. This is a totally distinct argument from suggesting that the presence of NPPs themselves increase the pre-existing risk through their ability directly to provide weapons material. Nevertheless, their presence may be sufficient to compound difficulties of international overseers in detecting weapons activity. Should you consider that the points made in this paragraph have any validity, what would be your own suggestion for addressing this enhanced proliferation risk? In particular, do you think different approaches to enrichment and reprocessing (in particular, pyroprocessing) offer any benefits?

Hi Douglas,

re: /3

There’s a SCIAM article (you have to buy to read the main text)

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=local-nuclear-war

The wiki says:

“Potential consequences of a regional nuclear war

A study presented at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union in December 2006 asserted that even a small-scale, regional nuclear war could produce as many direct fatalities as all of World War I and disrupt the global climate for a decade or more. In a regional nuclear conflict scenario in which two opposing nations in the subtropics each used 50 Hiroshima-sized nuclear weapons (ca. 15 kiloton each) on major populated centers, the researchers estimated fatalities from 2.6 million to 16.7 million per country. Also, as much as five million tons of soot would be released, which would produce a cooling of several degrees over large areas of North America and Eurasia, including most of the grain-growing regions. The cooling would last for years and could be “catastrophic” according to the researchers.[15]”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuclear_war#Potential_consequences_of_a_regional_nuclear_war

This is from Science Daily, which has more detail… but the final paragraph is of great interest!

“”With the exchange of 100 15-kiloton weapons as posed in this scenario, the estimated quantities of smoke generated could lead to global climate anomalies exceeding any changes experienced in recorded history,” Robock said. “And that’s just 0.03 percent of the total explosive power of the current world nuclear arsenal.””

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/12/061211090729.htm

The nuclear winter wiki summarily states that a full exchange of today’s weapons, about a third the total at the height of the Cold War, would cause:

“A global average surface cooling of –7°C to –8°C persists for years, and after a decade the cooling is still –4°C (Fig. 2). Considering that the global average cooling at the depth of the last ice age 18,000 yr ago was about –5°C, this would be a climate change unprecedented in speed and amplitude in the history of the human race. The temperature changes are largest over land … Cooling of more than –20°C occurs over large areas of North America and of more than –30°C over much of Eurasia, including all agricultural regions.”

But laugh it up, because DV8 simplifies terrorist access to nukes as unlikely because, after all, why they didn’t use them in 9/11? So don’t worry be happy! Nuclear weapons are almost as good as nuclear power! Anything with “nuke” in it appears sacrosanct.

DV8, your analysis in the opening post was somewhat comforting, but does not eliminate the possibility. All you have done is lower the range of possibilities in my mind, not limit it to zero which is what you seem to think you have proved which I find deplorably deceitful. Some of the arguments were outright simplistic.

Go back to the science of nuclear power, because your arguments over sociological and political possibility are just not as watertight and don’t carry the weight of experience and analysis in these matters.

And Barry? Please reconsider letting someone submit articles written so far outside their ‘field’. That article was a poorly written propaganda piece by someone that seems to love WMD’s. It was largely an opinion piece with a tiny bit of politics thrown in. Poor form for this blog, really.

eclipsenow, My review of renewable storage systems suggests, that molten salt storage with a solar thermal heat source would be the most cost effective renewable storage system, but that if you want to heat molten salts for storage, a molten salt reactor would be a far more cost effective source of storable molten salt than a solar thermal plant would be. You cannot escape the rational for nuclear power, by claiming that energy storage research would lead to a superior, more cost effective renewable alternative to nuclear power.

DV82XL, South Africa completed their bomb design well before they had the fissile material available.

Their design was also reliable with 80% enriched uranium. Not only does this make the critical mass higher and reduce the yield, but as I understand it the spontaneous fission rate of U-238 is higher than U-235, so the minimum insertion speed for a reliable bomb using lower-enriched uranium is therefore higher (though calculating how much higher is well beyond the limits of my knowledge).

At the risk of again arguing from authority, may I quote Luis Alvarez?

@ Eclipse Now: I agree that certain rules of scientific or academic discourse are having a coach and four driven through them on BNC at this juncture.

I also agree with your observation on DV and WMDs, a topic which he floated on the current Open Thread. He got no takers for it at the time bar myself, pronounced himself correspondingly insulted and withdrew (loc.cit.)

There are good reasons why peer review and referees exist. But more to the current point is what I described some weeks ago as a certain magisterially ex cathedra stance on the part of the gentleman.

Thus I do not think it is acceptable to write on topics covering half a century of various types of history without sourcing what one says and then to graciously advise readers to “background themselves.” Because science rests on the reproducibility of results and transparency of experimental design.

In other words, without knowledge of which primary and secondary sources (terms used as the historian uses them) were used on site in Quebec, the outcomes desired are not likely to be replicated, if one views his injunction to BNC readers as a sort of experimental design.

Note to natural scientistson this blog: unsourced screeds get short shrift in the social sciences for good reason, irrespective of whether “the facts are surprisingly simple to understand” (quote).

However, the gentleman in question has drawn at least 2 long bows on previous occasions, viz.. 1 that most anti-nuclear activity is a front for fossil fuel interests 2. that the anti-proliferation bureaucracy is only in it for the money (I am quoting from memory on 2., but I believe that was the gist). So his current post is not a new departure.

None of the above is to be construed as addressing the fraudulence or otherwise of the War on Terror.

It follows from the above that anti-nuclear activists are inadvertently increasing the power of states with nuclear weapons, and thus increasing the incentive for other states to have nuclear weapons. By confusing the issues between nuclear power and nuclear weapons these activists are also preventing any viable solution to the threat of catastrophic climate change.

Douglas Wise –

Your first point. Yes that has been my position on the matter for some time, elsewhere I have written at length on the need for the pronuclear community to emphasize the fact that nuclear power and nuclear weapons are separate matters that have little to do with each other.

Your second point. I would think that if some subnational actor managed to lash something together that looked like it might be a device, their best strategy would be to announce its existence and hold it in reserve. Because, in the end the chances of it being a fizzle is very high and a great deal of effort would have been wasted. A nuclear weapon’s primary value is as a threat, this would hold for terrorists as well. Thus I do think the actual destructive potential of such a device would be of secondary importance.

Your third point. The ‘nuclear Winter’ hypothesis has yet to firm up sufficiently to give any reliable numbers of thermonuclear explosions required or the time-frame they would have to happen in for me to hold an opinion.

I would note however that this is based on the supposition that any nuclear attack would necessarily become a full exchange with all Powers launching all their weapons. This is again an outmoded idea based on strategic thinking in vogue in the Sixties. Nuclear planning and doctrines have moved forward and this sort of battle between two superpowers is now very unlikely.

Robert Merkel – statements like i“if they had such material, would have a good chance of setting off a high-yield explosion simply by dropping one half of the material onto the other half.” are exaggerations and I am sure Prof. Alvarez meant is as such.

Nevertheless he is trivializing the technical task of making this type of weapon and having it function reliably. At the risk of repeating myself, this is not out of reach for a state (or perhaps an institution like the University of California, Berkeley where Alvarez spent his career) but it is not a task that any terrorist is up to.

Peter Lalor – I was not under the impression that BNC had the same standards as an academic journal, it would seem too that the owner of this site didn’t get the memo ether. If it wasn’t clear from context, this was an opinion piece on the 2010 Nuclear Summit and the emphasis placed on HEU at that meeting.

In the thirty-five years or so that I have been reading them, even the academic journals allow more latitude in their editorial submissions than they do for articles.

One of the reasons I ask people to look into these matters themselves is that most of the people I interact with on this subject properly take a very jaundiced view of what they see on the web, and indeed supporting documents for just about anything, no matter how bizarre can be found with all the outward trappings of a scientific paper.

Understanding this matter of nuclear weapons however, requires some deeper background in the technical fundamentals of the subject and the military doctrines attached to them to reveal just how out of sync common understanding and the political rhetoric are with reality. What I wish people like you and others here with the intellect to do so, is go through the same journey I did, because that is the only way you will be convinced.

If anyone wishes to start someplace I can suggest the essay on nuclear policy making The Nuclear Game by Stuart Slade that I shamelessly quoited from up-thread.

http://homepage.mac.com/msb/163x/faqs/nuclear_warfare_101.html

http://homepage.mac.com/msb/163x/faqs/nuclear_warfare_102.html

http://homepage.mac.com/msb/163x/faqs/nuclear_warfare_103.html

Slade was a planner back in the days. You will find his observations enlightening, and a good departure point should you wish to pursue the topic further.

Don’t lecture me on what I can/cannot put on BNC. This is a personal blog, not a formal technical journal, which has its own (often peculiar) set of constraining rules. Blogs are all about opinions. As to the degree with which they are supported, or not, that is up to the readers and commenters to decide themselves. No one forces them to read any of the postings, or make comments, or agree with what the post says. An ‘open science’ blog like BNC simply gives anyone an opportunity to read an opinion, and then judge/debate the merits or demerits of that argument with other like-minded people. On that basis, DV82XL’s post fits perfectly with the spirit and intention of BNC. I find it perplexing that you and Peter Lalor don’t seem to grasp this fairly simple (and near universal) premise on which blogs are based.

Peter Lalor, on 16 April 2010 at 21.35 Said:

“However, the gentleman in question has drawn at least 2 long bows on previous occasions, viz.. 1 that most anti-nuclear activity is a front for fossil fuel interests 2. that the anti-proliferation bureaucracy is only in it for the money (I am quoting from memory on 2., but I believe that was the gist).”

The first is essentially correct. The antinuclear movement is a religion. This religion says that nuclear energy is “bad.” The definitions of good and bad are in the minds of the faithful. They are the useful idiots, if you will, of those who wish to continue the status quo of carbon-based fuels. The fossil fuel industry is using them to persuade the world that continued use of their products is mankind’s wisest course of action.

Wind and solar are stupid little toys; they will forever remain toys. They will never power an advanced civilization. They are a waste of our economic resources, our attention and our time.

The second is incomplete.

In my opinion, two parasitic cultures have grown around nuclear technology, both artifacts of Cold War paranoia: first is the radiation protection industry and professionals working in the field that depend on the continued acceptance of the the linear-non-threshold dose-response model, despite the fact that this model has been thoroughly discredited on multiple occasions.

The second is the nonproliferation organizations. This latter having no more of an evidentiary foundation than the former, but is similar in that a host of people depend on its assumptions for their jobs. The NPT has done nothing to stop the spread of weapons except in the minds of the functionaries of the bureaucratic apparatus it precipitated, but has created all sorts of onerous rules that have increased the administrative overhead of nuclear energy without doing one damned thing to slow proliferation

Anti-Nuclear activists are like American Republicans, they know what they are against, but they are far from sure what they are really for. eclipsenow, tells us he is against nuclear war, and tells us how terrible it would be. Of that i have no doubt, but i haven’t the foggiest idea how he would go about preventing nuclear proliferation. Anyone who believes that they know how to stop the spread of nuclear weapons, should demonstrate that the solution would have prevented Pakistan from acquiring nuclear weapons if it solution had been in force. The Pakistan test would require that anyone who proposes a proliferation prevention policy give a detailed and reasonable answer to the question, that would describe how the solution would have applied to the known circumstances of Pakistani acquisition of nuclear weapons. If the an anti-proliferation policy would have prevented Pakistan from acquiring nuclear weapons, then it begins to have credibility. If the answer for Pakistan is satisfactory the questions should also be posed for the South Africa and the North Korea cases.

So far none of our anti-nuclear friends have offered to tackle the Pakistan test, and indeed have offered us nothing that suggests they have a serious interest in the actual spread of nuclear weapons. What they have a serious interest in is preventing the spread of nuclear power reactors.

I don’t agree.

In a world without nuclear weapons it becomes thinkable to acquire and use nuclear weapons offensively.

Access to delivery systems will become far more ubiquitous and far cheaper as part of the drive towards cheaper access to space. See the flurry of private companies either trying or succeeding in accessing to sub-orbital space and LEO. There’s even a company trying to build a hydrogen gas cannon(no combustion, just heated hydrogen, most of which is recaptured and re-used) which can launch small payloads at 6-8 km/s; which is enough that you only need a small single state rocket to reach LEO. This gets rid of the slow and vulnerable boost-stage of a nuclear weapon and it has a lower bound launch cost of ~$100/kg payload, more realistically a few few hundred bucks.

The intended market is for launching small satellites and for transporting fuel into LEO. If you can build a fuel depot in LEO you can use it as a staging area for a permanent Moon base or manned mission to Mars.

No. Bush, Cheney and the rest of the neocons have done fairly well for themselves and were never at any real risk of death.

Nuclear weapons have this wonderful property no other weapon in the world has; they just as easily destroy the political elite of a country as they kill civilians or soldiers. In fact, the political elite is more likely to be targeted than civilians or soldiers are. Stalin killed almost everyone he ever worked with and instituted a system of slave labour camps which killed millions through not feeding or clothing them properly. You think he’d be bothered by killing tens of millions of his own people in a conventional war?

Hi Douglas Wise,

are you comforted by DV8′s mere assertion that:

The ‘nuclear Winter’ hypothesis has yet to firm up sufficiently to give any reliable numbers of thermonuclear explosions required or the time-frame they would have to happen in for me to hold an opinion.

Wow. That’s won me over. He totally debunks the peer reviewed scientific papers I quoted! I guess in his mind, one assertion by DV8 overturns a dozen peer reviewed papers. 😉 Don’t worry, it’s not just you. This is just his style. Arrogant dismissal with a few words and nothing to back them up.

would note however that this is based on the supposition that any nuclear attack would necessarily become a full exchange with all Powers launching all their weapons.

And again, another of DV8′s favourite argument tactics, the straw-man! Dude, only 1 of the papers I quoted above mentioned an all-out attack for the ‘nuclear winter’ scenario. The other papers are about more limited exchanges of maybe 50 Hiroshima sized weapons, which would increase global dimming to the point where agriculture would be severely affected. Check out the papers I quote. Oh, and before you sneer at the wiki quotes, check the PAPERS they are based on.